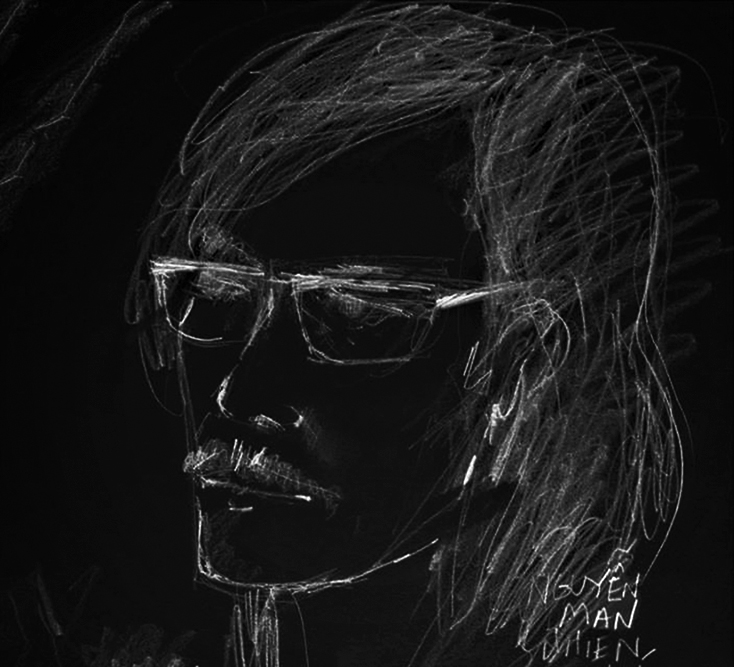

asemic 15

Compiled by Tim Gaze

I was at a tram stop recently when a woman walked past wearing a black dress. There were short white threads sewn onto the material. Each thread was stitched leaving the ends to dangle. These dangling ends reacted to her movement and the gusts of wind, forming individual character-like shapes. I found myself mesmerised, particularly because I had been asked to write this review, and was contemplating the meaning of asemic.

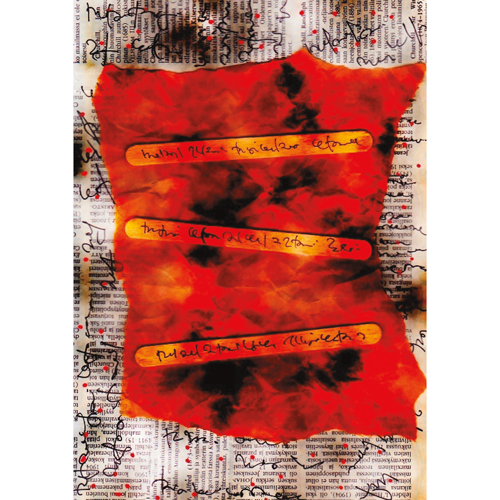

Asemic writing focuses on the visual aesthetics of written language without the legibility of writing per se. Though uninterpretable, according to Tim Gaze, the editor and publisher of asemic 15, asemic writing must mimic what we know to be writing to an extent, so as to differentiate itself from visual art. Some, like Todd Burst, would describe it as the textual residue of writing; others state it lies in the realm of the pre- or post-literate. For artists such as Rosaire Appel, whose work is represented in the magazine, it is more about context. Appel states in zoomoozophone review: ‘Perhaps it has less to do with the graphic itself than the space or territory it resides in.’ Many books of asemic writing have been published and a community of practitioners has formed, some of whom may well feel disenfranchised from more mainstream art / literary communities. Though nebular and possibly confusing, the term asemic is now being used more widely in criticism.

I recognise the importance of endeavours that intersect the writing / drawing divide, however, when first gathering texts relating to asemic writing, the cautionary words of Britain’s conceptual artist Victor Burgin came to mind:

Interpretation requires … tracing of alliances and elegances, dependencies and conflicts between the work in question and the context within which it is produced … In the absence of interpretation we are left with the brute obviousness of the literal content of the work and the manifest declarations of its author and their consensual echoes.

Or perhaps put more simply by TS Eliot: ‘No poet, no artist of any art has his complete meaning alone’. Interestingly, the word asemic does not exist in the Oxford Dictionary or the Macquarie, however it is defined in the 2015 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Psychology:

n. Impaired ability to encode or comprehend signs such as gestures (1) or the spoken and written signs and symbols of human languages. Also called asemasia or asymbolia.

Michael Jacobson and Tim Gaze have written about asemic writing as a ‘wordless open semantic form of writing’:

The word asemic means having no specific semantic content. With the non-specificity of asemic writing there comes a vacuum of meaning, which is left for the reader to fill in and interpret … free to arbitrary subjective interpretations … True asemic writing occurs when the creator of the asemic piece cannot read their own asemic writing … Even though it ‘is traditionally “unreadable”, it still maintains a strong attractive appeal to the reader’s eye’.

Gaze, to an extent, has controlled the discourse. Wikipedia tells us that he is both the producer and mediator of meaning and, in the process, constructs his own artistic and public identity. Disagreements about the definition however, started to appear on the site towards the end of 2016. Co-founder Jim Leftwich is quoted to have said: ‘it is not possible to create an art / literary work entirely without meaning.’ From the information made available online by Leftwich, concerns have been articulated since 1998. In 2012, ‘Olen’ writes on slowforward.me:

How is it possible for anyone already possessing a language to produce something in another ‘projected’ or ‘imagined’ sign system where the producer pretends to have no access? Isn’t asemic writing a species of fantasy?

A 2013 interview between Quimby Melton and Michael Jacobson illustrates just such a quandary:

Melton: […] Since they usually cannot be “broken” – that is, translated into objective carriers of meaning – one can interpret asemic texts as the ultimate encoders of personal insight and reflection. Everything from a little sister’s journal to the rape fantasies of a poetic psychopath could be safely housed in asemic glyphs […]

Jacobson: I have put some of my ugliest and most beautiful thoughts into my asemic texts, and that’s where I’d like these thoughts to stay.

To label a work as asemic, may infer some kind of code or post-truth vessel. Here, illegibility to the reader is seen to be the foremost intention of the work regardless of whether it is actually illegible to the writer.

For Jacobson, interpretation or critical engagement with asemic writing is unwanted. And he is not alone. Gaze, too, views ‘the usual modes of literary analysis taught at Universities… as being similar to the way animals are judged at an agricultural show.’ Similarly, The Asemic Manifesto 111 states:

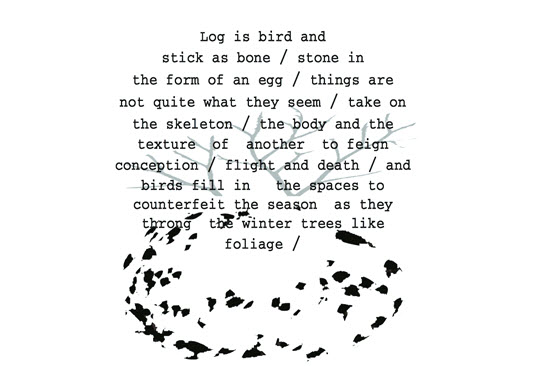

For argument’s sake, if we take the work as having the conditions of asemic writing (illegibility for the writer and reader), we can see aesthetic arrangements that are an expression of influences, emotions, histories, experiences, prejudices, biases and politics, intended or not. There is no ‘void of meaning’, nor is there what Jacobson calls a ‘non-specific universe of points.’ Instead we find a conundrum: to call something writing without any semantic content is a curious premise. It relies, in the words of W J T Mitchell, on ‘relations and distinctions, that crop up in aesthetics, semiotics, accounts of perception, cognition and communication, and analyses of media.’ The context of art encompasses these relations and distinctions. Art by its very nature seeks to draw our attention to paradoxes, open ended-ness, new ways of expression, the uncomfortable, the tensions and the failures. Art asks us to think. There is a sense of infancy within the realm of asemic writing. As illustrated in the Quimby / Jacobson interview, contradictions give rise to questioning the authenticity of the work. Subjective categorisations also restrict visual and conceptual possibilities that may provoke insight in this field. (The sci-fi film Arrival 2016, comes to mind as an imaginative ‘probing’ of communicative possibilities.) Examples such as ‘attractiveness’ as a criterion for ‘successful’ asemic writing, as well as having a ‘likeness’ to known writing styles come to mind.

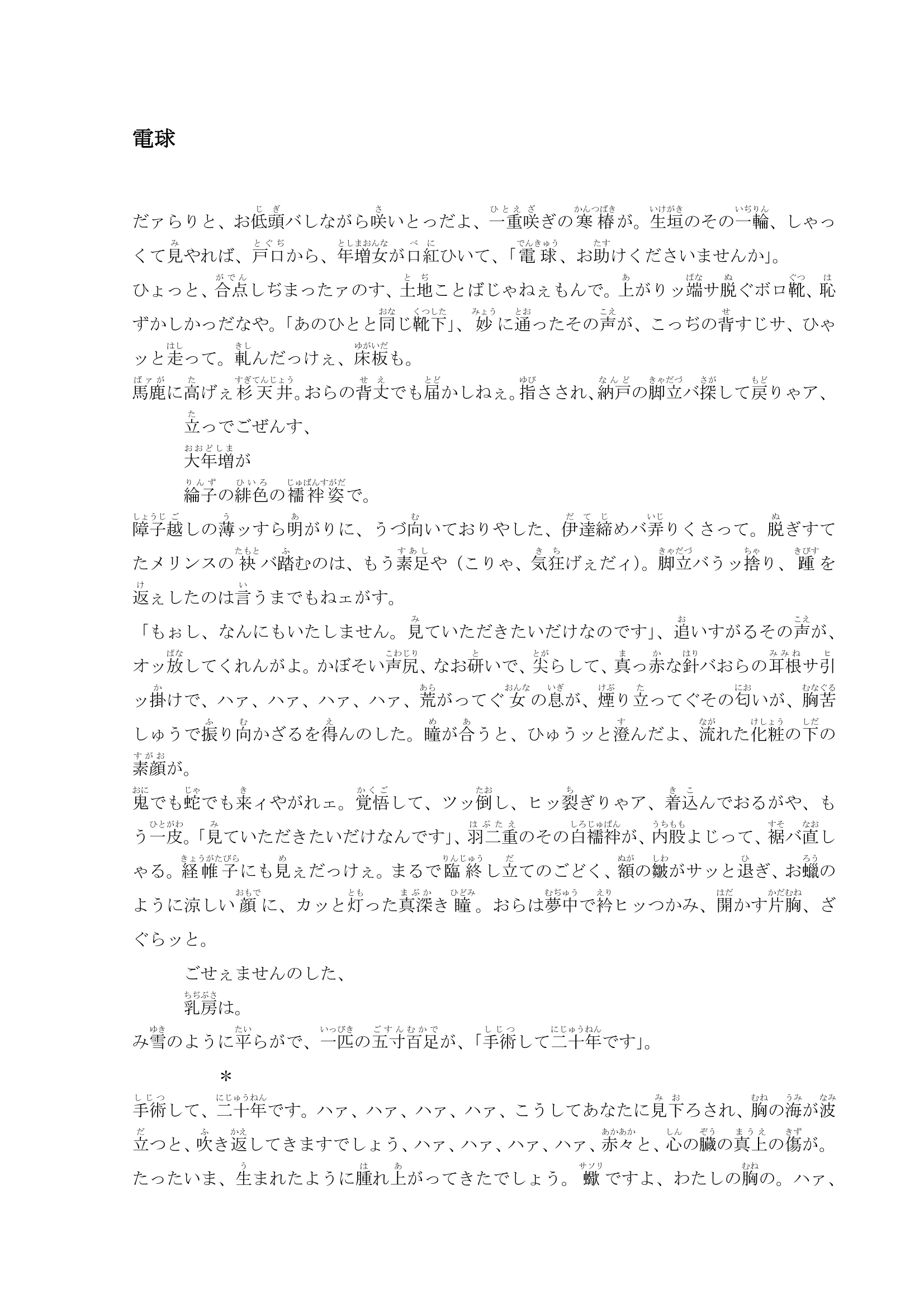

Rosaire Appel’s 2009 video piece Liquid Calligraphy questions the term asemic writing in relation to meaning. The video illustrates lines ebbing and flowing in a vertical motion that one may associate with sound recordings (having said that, much of the movement becomes full circular motions of lines). Though the video has been rotated on its side, there is just enough visual information given to understand that the moving image is surface reflections on water. Tonal contrast has been pushed to the extreme, allowing only black and white without any gradation of tone. Prior to this moving image, the video shows typed text stating ‘a piece of the – Hudson river tries to pass as – asemic writing’. The accompanying sound of passing cars and trains is slightly digitised. Appel seems to be playfully questioning the artist’s ability to ‘not know’ the content of their own practice, or how content becomes asemic. Surprisingly, as it is clear from her website, she relates to the term positively.

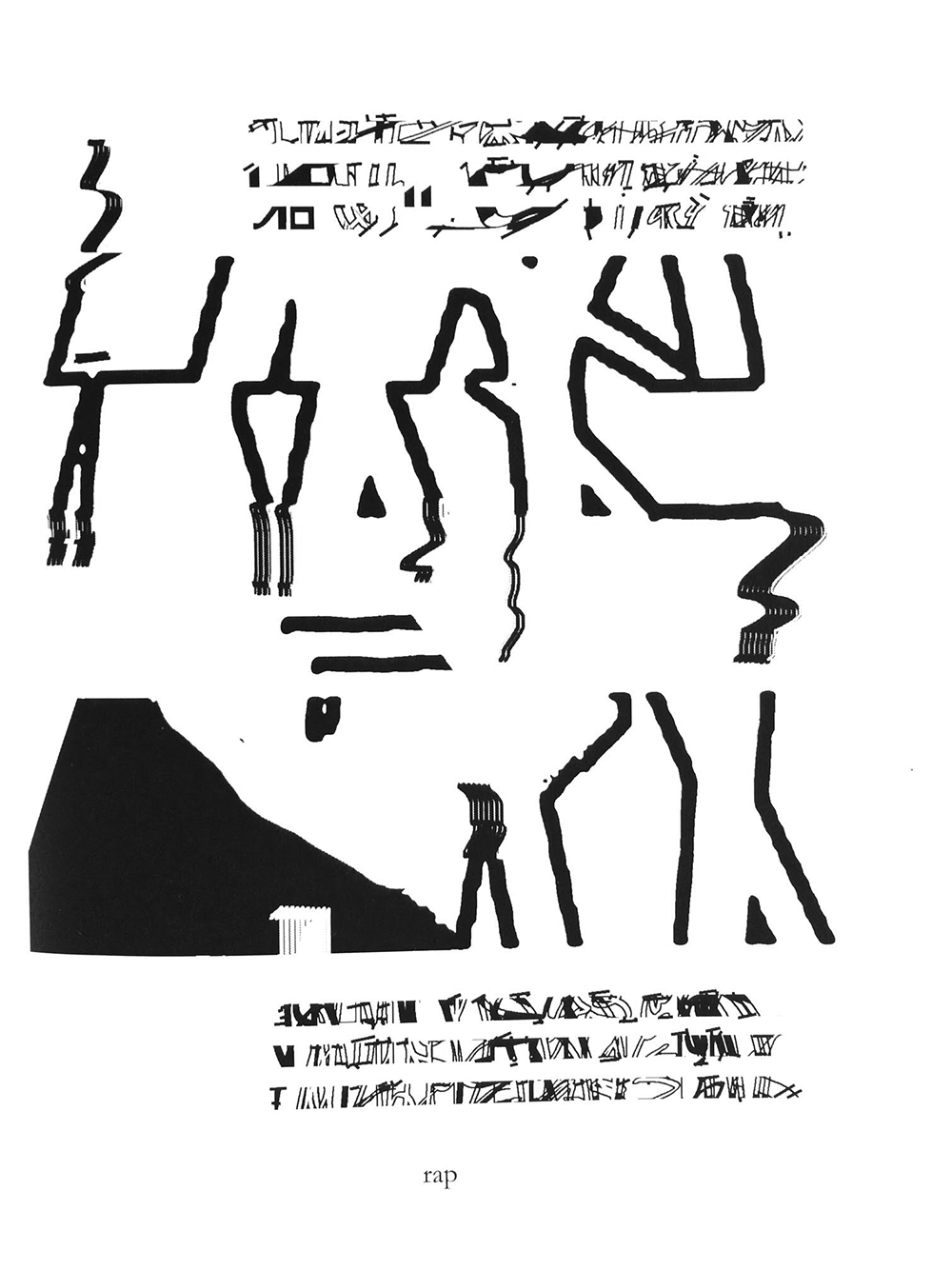

Appel has two works illustrated in separate locations in asemic 15. One is almost identical to an image from a book-in-progress series uploaded in 2010 under her asemic stories webpage. It is almost like Appel is demanding these marks be both pictorialised – where the marks are ‘enlarged’ and slightly contorted in the central section of the page (to be seen in space) – and ‘read’ – where the marks are clearly delineated into small vertical rows at the top and bottom of the page (thereby occupying time). Was the ‘writing’ originally a singular interconnected work and then vertical sections digitally erased to create rows? The lines in the central section of this page give a sense of torso-ness, a weighted centrality where lines taper in, and at either end, a sense that the lines have been cut. This is an artist whose documentation online shows that she has clearly worked in this field between writing/drawing in an extended way, and for some time.

Images courtesy of the editors

Images courtesy of the editors Image courtesy of the author.

Image courtesy of the author.