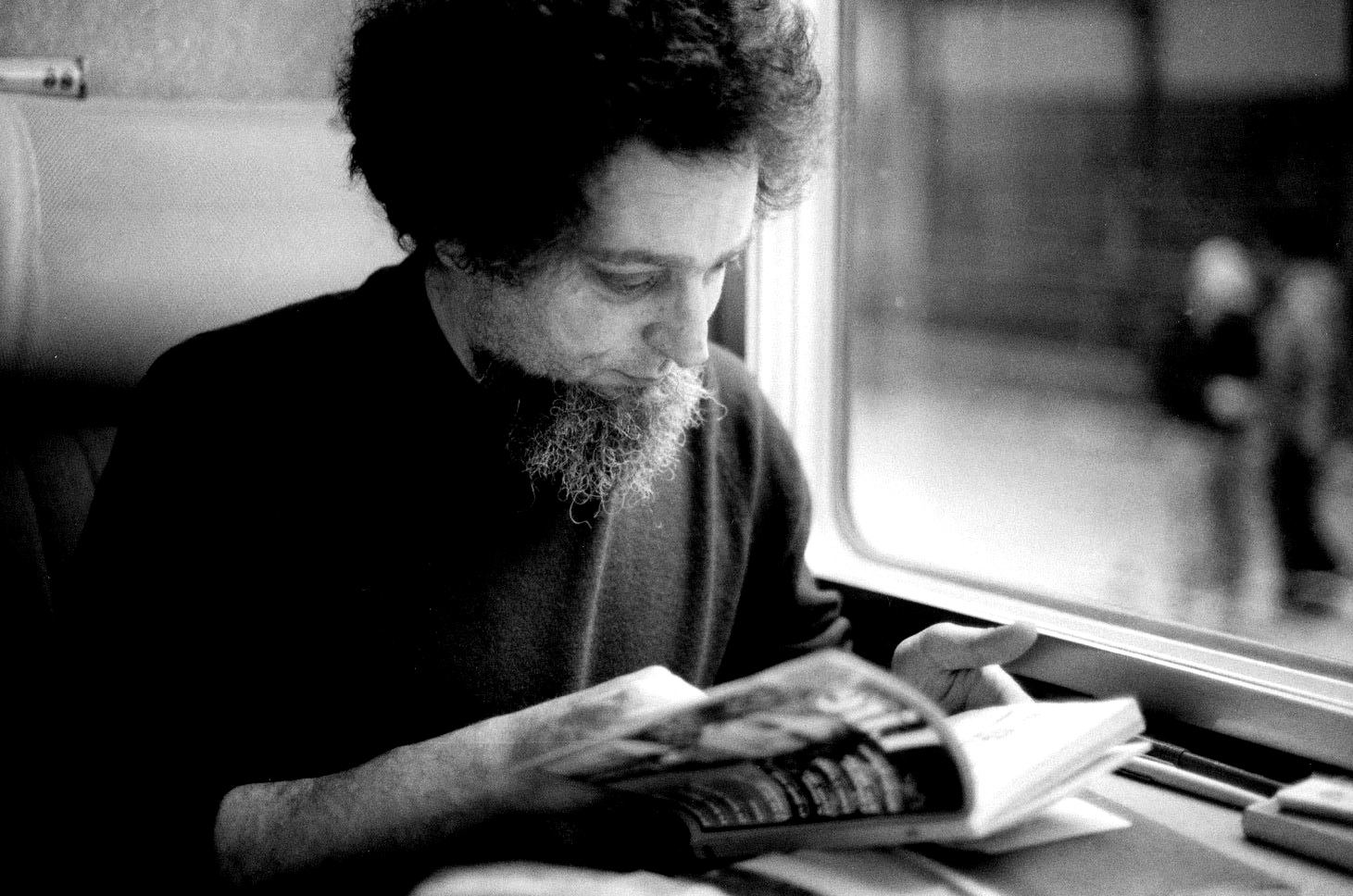

‘write prose and cut your margins,’

a friend and editor advised

— Brian Castro (22)

Blindness

The blindness presented here is metaphorical, if not phantasmagorical, for Castro calls his verse novel a ‘Phantasmagoria […] in thirty-four cantos’. For me, actual blindness in Paris is a curse. That said, the beauty of Paris belies the misery and grief of war, colonialism and slavery.

Some people argue that postmodernism itself has driven our society blind, and that it has taken cataclysmic events for us to see again, such as the atrocities of September 11, 2001 (‘I’m too blind for your masked ball’ [67], the protagonist Lucien Gracq says in an unposted letter [‘Snail mail is blind’ (196)] when invited to join the Club des fugitifs, the thinly disguised Oulipo movement, wishing instead ‘he had taken up the offer / of a residency at Varuna’ [ibid.], rhyming the Blue Mountains writers’ residency with ‘doona’. Undercutting with humor is a common postmodernist device.). Castro does not mention 9/11 but does other violent upheavals and wars, such as the Easter Rising, the First and Second World Wars (the notorious Vél d’Hiver, in Paris, now commemorated with a plaque) and even the Battle of Waterloo as a kind of battle of the sexes (45; undercutting again).

‘Canto’ is an Ezra Pound word (or a Dante word – after all, Castro does say his novel is written in 34 cantos, just like Dante’s Inferno). Similarly, ‘Duino’ belongs to Rilke; ‘mauvaise foi’ (‘bad faith’), to Sartre; ‘madeleine’, to Proust (Castro references this three times), ‘erasure’, to Derrida; ‘frog’, to Bashô; ‘archetype’, to Jung; or as ‘wasteland’ (65) – written as two words – belongs to Eliot. With regard to the literary process known as erasure, I wrote elsewhere that I believe ‘erasure’ – rature in French – is Derrida’s pun on his favorite lexicographer, Émile Littré and litté-rature. (It may have been taken seriously by Derrida himself as time wore on, and may be taken seriously by others to this day, but I am convinced ‘erasure’ started out as a piece of fun.)

Blindness is part of the paraphernalia of prophecy, the stock in trade of seers, the most famous of whom is Tiresias, a transgender man of Greek tragedy whose first gig was as advisor to Cadmus who, according to legend, introduced the Greek alphabet to people. A blind man is a stock character of Noh plays (signified by a mask), if we go from West to East. The mask allows for different personalities, impersonations, transformations, or a change of sex even; a mask provides for identity as well as disguising it.

Castro is not blind to popular culture either – he mentions everything from Giorgio Armani, Charles Aznavour, Jacques Brel, The Postman Always Rings Twice (‘the postman doesn’t even ring twice’ [173], but as Gilbert Adair maintains, The Post-Modernist always Rings Twice), ‘Sex and the City’ and the Adelaide Festival to The Big Issue, Charlie Hebdo, the Titanic (twice!) and the Tour de France bicycle race (‘the Tour de France / come through Proust’s Combray’ [133]). He can be high-brow, too, listing Tel Quel, The Maids (an outline, quelle qu’elles), Dangerous Liaisons (as lower-case text), discussing or mentioning Abélard and Héloïse (Abélard et Héloïse, Love Story for the Middle Ages), Pataphysicians, Pessoa, Pasternak, Proust, Adorno, Apollinaire, Bataille, Baudelaire, Beckett, Benjamin, Buñuel, Caillois, Céline, Césaire, Dante, Freud, Giono, Heidegger, Huizinga (Homo Ludens is a seminal work), Jabès, Kafka, Kant, Keats, Klossowski, Koestler (not mentioned by name), Lacan, Leiris, Marx, Milton, Modiano (should he be in the popular culture list?), Montaigne, Nietzsche, Ocampo, Queneau, Roussel (not Rousseau), Sade, Satie, Tolstoy, Verlaine, Whitman, et al. (A long list that could have been longer, for Castro is critiquing Australian academia’s love affair with French theory. That said, Jacques Derrida, the father of Deconstruction, is missing in person, if not in action. The closest we come is ‘Doctor Nietzsche [Philip Nitschke] / who would make a laptop available / replete with all the paraphernalia / to guarantee Gracq’s erasure’ [134; see above]. The parochialism of Nitschke versus the international stature of Nietzsche. Duchamp is also missing by name, but his cross-dressing alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, also a pun [éros, c’est la vie], is there. And let us not forget that Flaubert is on the front cover.) Lots of embedding in the text, such as ‘invitation to voyage’ (50), which is Baudelaire, of course. Mixing high culture with low is a hallmark of postmodernism. (Jokes are another hallmark – in-jokes or otherwise. So is nonsense.

As Jack Spicer once said, we do not have to be forced to nonsense, that it is another discipline. Mixing high and low culture, then, but keeping the demarcations a formalistic certainty, is a Western concept. I remember some years ago admiring a painting by Dawn Sime and foolishly telling the artist that it reminded me of batik. ‘It’s all art, Javant,’ she said, correcting me, ‘There’s no craft.’ ‘[L]anguage without craft limits the ego.’ – Brian Castro, p. 68. Ambiguity. In the East, the borders between art and craft are not so clear; besides, it does not matter. In other words, such distinctions are a Western construct. For an example of mixing high and low culture, I found a later poem by Kenneth Koch, a precursor to the postmodernists, where he has excessively juxtaposed the Acropolis with Coca-Cola, Homer with Jack and Jill, Pinturicchio with a fruit-juice seller in Hawaii, Dostoyevsky with Walt Disney and Herbert Hoover with Popeye. Castro has done more or less the same by putting Rembrandt and Mr Mouse [167], Sparta and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde [‘Dr Jekyll in his hide’ 162], Virgil and ‘Roger the dodger’ Caillois [8], etc., on the same pages. Charles Bernstein, a leading figure in the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E movement, has stated that [post]modernism’s theory, being full of ‘elisions and evasions, obscure references [and] logical lapses’ is the kind of poetry that appeals to him, and appeals to many.)

Blindness as academia. Blindness as a disability overcome by art. (‘Jorge Luis Borges, who was blind for a large part of his life’ [179], a corollary to Beethoven’s composing music when deaf, etc.) Blindness as not recognising certain facts. (‘Not to notice that, not to see how love would end because of the rapidity of communication, is a special form of blindness’ [170].) Blindness as silence. (‘[Gracq] felt in need of secrets and silence’ [18] or ‘I remember that silence was the best communication’ [175]. Even American avant-garde artist John Cage gets a guernsey: ‘it was enough / to make silence meaningful’ [117].) Blindness as a kind of Bergeresque not seeing – on the last page of the verse novel, ‘Gracq grows blinder…’ (214). Having said this, Castro does not overdo the blind analogy, mentioning blindness just five times – and ‘blindness and rage’ (‘dying into writing was … well … / both blindness and rage’ [10]; ellipsis in original), four times – in the text.

A Coat of Ashes by Jackson

A Coat of Ashes by Jackson