PIECE II

I’m up late and through tired eyes I see a blanket of painted discs flash across the television screen. Under heavy rain two million of them move in unison down the street like a conveyer belt: blues, pinks, yellow, tartan, polka dot, black, teal, grey, transparent. The protestors form a hyper-coloured wave as they walk together along Hong Kong’s Central district in defiance of the police ban. A chant makes its way upwards through the cracks between the umbrellas:

‘Hong Kong people, keep going!’

How to describe this image? How can resistance suddenly look almost picturesque; like a city-sized mosaic?

Mosaic: a surface decoration made by inlaying small pieces of variously coloured material to form pictures or patterns.

also: the process of making it.1

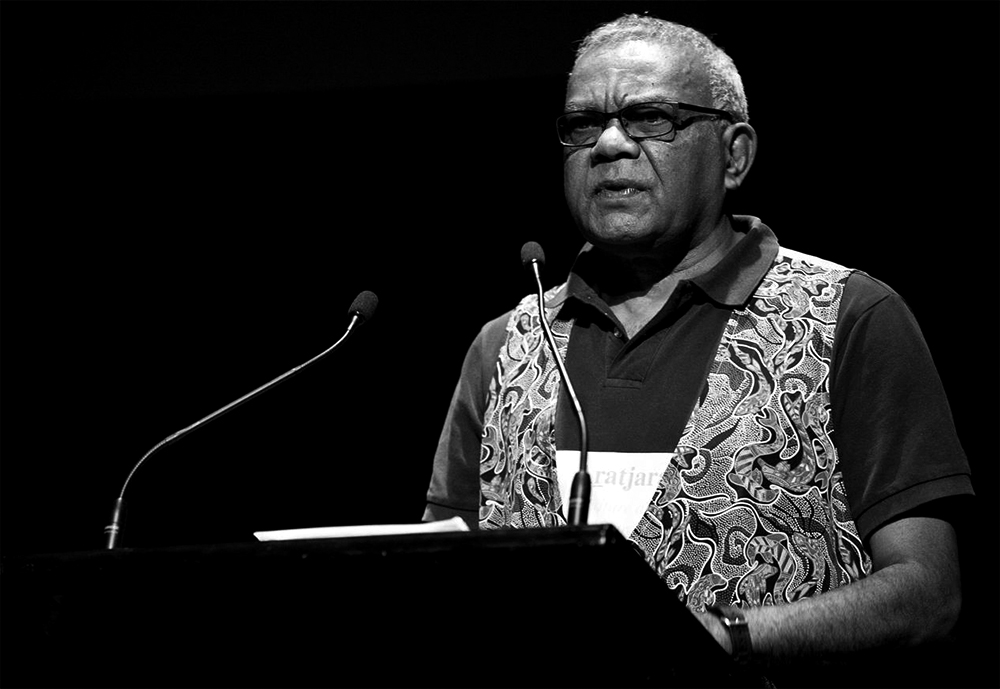

In an attempt to find a new and conceivably more accurate way of describing Fogarty’s work, I attempted to position a discussion of his poetics in the program of a conference on ‘Poetry & the Essay’, put together by Anna Jackson, Helen Rickerby and Angelina Sbroma at Victoria University of Wellington in 2017. The genre of the lyric essay seemed, at the time, a productive alternative to the restrictive models that label the lyric poem either an ‘intense expression of subjective experience’ or more recently ‘the fictive speech of a specifiable persona’, a phrase Jonathan Culler inscribes on the jacket of Theory of the Lyric (2015). There seemed to be some connection to the lyric essay in the way Fogarty’s writing disrupts logic by imposing unexpected linguistic inflections on the reader, inverting the system of English language itself. After all, the Fall 1997 issue of Seneca Review unveiled the lyric essay as a form that, to quote John D’Agata and Deborah Tall’s introduction, ‘gives primacy to artfulness over the conveying of information, forsaking narrative line, discursive logic, and the art of persuasion in favor of idiosyncratic meditation … {T}he lyric essay often accretes by fragments, taking shape mosiacally … storyless, it may spiral in on itself, circling the core of a single image or idea, without climax, without a paraphrasable theme.’2

One of Fogarty’s most persistent methodological preoccupations is with the concept of the poetic text as a mosaic; the construction of poetry as mosaical. His previously unpublished 2012 collection, Broken Mosaic, ends with a poem titled ‘Mosaic’. The first half reads:

Earth tears all native lands All misery spreads in rich bodies of iron All beauty horizons in the poorest zones Open the grounds alighting to surrender Sing and dance in grand fountain wars Earth beings here share my poverty in all personal Our way to the one lingo where ever fingers touch Our hands are free to arms We found peace made to blank the storming banks3

The beginning of the poem evokes a scene in which the earth itself splits into pieces like a broken mosaic. There’s a doubling in the wordplay of ‘earth tears’ in that the land stolen from Aboriginal people is both torn apart (it tears) and the earth’s tears seep into ‘all native lands’. The unmistakably songlike, incantatory quality of Fogarty’s verse is clear in the half rhyme of ‘blank’ and ‘banks’, where English ruptures, unable to hold its centre. The semantic slipperiness of Fogarty’s poetics, in which non-Aboriginal words appear unable to realise their own meaning, is suggestive of not one but multiple techniques at play simultaneously. It is both highly modernist (Stein-esque, perhaps) and yet inseparable from ancestral speech. In Fogarty’s self-described mosaic, we see the tessellation of multiple modes of speaking and being as well as, overarchingly, the ‘inheritance of Aboriginal oral, collective, and performative traditions,’ as Stuart Cooke has written4. The effect of this fusion is, particularly for white readers, unsettling; it is the manifest ‘guerrilla surrealism’ of a ‘spectral presence’, in Philip Mead’s words5. Fogarty forges a mosaical poetics of the kind that shifts and expands unexpectedly since the pieces don’t stay in the same place for long.

In 2017 I asked Lionel about his concept of the poetic mosaic. His response:

‘What I try to do to English is to destroy it mosiacally. Some people see the intellectual and academic and the ‘proper way’ of speaking, but broken English makes sense to be in poetry – Creole language, crisscross of pub talk, and whole array of other language – this mosaic language reflects the world more accurately.’

I asked if the intent of this was to confuse or alienate the non-Indigenous reader. Somehow we ended up talking at length about Bob Dylan. And then Lionel commented:

‘A mosaic language will help them better their technical use of language. In terms of the mosaic of political poetry, it’s important to understand how language works; mosaic is a better understanding of all language. The idea of mosaic isn’t to puzzle people, it’s looking for a positive outcome. Dylan mosaically tangled it all up and waited for the right word to come through.’

The second half of ‘Mosaic’ offers some indication of this kind of tangling:

What makes a land cry incurably? For all people’s poor are richer Even if tomorrow’s truth is housed by the well off Many birds are spotted in a torched eclipse Many birds’ spirits may torch my feelings Saluting skeletons can payback no feelings Protect the unbenefited environment Judge the cover off our book and buy it Mosaic lives in a no words world!

The idea of a vernacular that lives outside of or separate to language (‘in a no words world!’), as Fogarty seems to suggest in the poem’s final line, reinforces not simply his estrangement from and destruction of English, it also signals something very particular about the unresolvability of his oration. The irony is that in every attempt to close read Fogarty’s poetry (as I am doing here), the joke is always on the critic. Reinforcing this idea, Fogarty told Dashiell Moore in an interview earlier this year:

‘Just cause you’re an English teacher, you can’t teach us about language. We’re teaching you the English, our upbringing and lexi-grammatical values gives us confidence to say that even if we are with the highest English teaching, we’re teaching them about how language works culturally.’6

Despite this, and as the pictorial significance of the mosaic indicates, language is always subordinate to Fogarty’s inherited imaginary; to the dreams and images that cannot be accessed by even the most astute reader. As he writes in ‘Return, Me Never More Returnin’’:

Hesitate not in this readers, cos my one even all parts of dreams elevates these images7

- Merriam Webster dictionary definition: mosaic. Online. ↩

- John D’Agata and Deborah Tall, ‘Introduction’. Seneca Review Vol. XXVII, no. 2 (1997) ↩

- Lionel Fogarty, ‘Mosaic’, p. 257. ↩

- Stuart Cooke, ‘Tracing a Trajectory from Songpoetry to Contemporary Aboriginal Poetry’ in A Companion to Australian Aboriginal Literature, ed. Belinda Wheeler (Boydell & Brewer, Camden House, 2013), p. 101. ↩

- Philip Mead, Networked Language: Culture and History in Australian Poetry. (North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly, 2008), p. 428. ↩

- Lionel Fogarty and Dashiell Moore, ‘‘The Rally is Calling’: Dashiell Moore Interviews Lionel Fogarty’. Cordite Poetry Review. 1 February, 2019. ↩

- Lionel Fogarty, ‘Return, Me Never More Returnin’, p. 158. ↩