Solid Air: Australian and New Zealand Spoken Word

Solid Air: Australian and New Zealand Spoken Word

Edited by David Stavanager and Anne-Marie Te Whiu

University of Queensland Press, 2019

Is an anthology greater than the sum of its parts? Does it effectively capture its milieu? Who’s been included, who left out? Is it genuinely of the moment? Will it endure? The case of Solid Air is even more complex. This is a collection of spoken word that’s been published as a book, rather than as a downloadable album, a film to be streamed, or a live show on tour (though there have been a string of impressive launches). Voice turned to ink, accent and emphasis turned into font, the unfolding of a poem in time turned into a presence on paper which is there in its entirety at one glance. Is this the stage surrendering to the supposed dominance of the page? Should I consider these poems purely in their physical form here, or as reminders of their performance elsewhere? Of course, editors David Stavanger and Anne-Marie Te Whiu know you’ll ask these questions, and it’s proof of their adept curation of voices that – while such questions persist after reading, transformed into something more productive – the poems themselves overwhelm any theoretical position or argument about what or who this anthology represents.

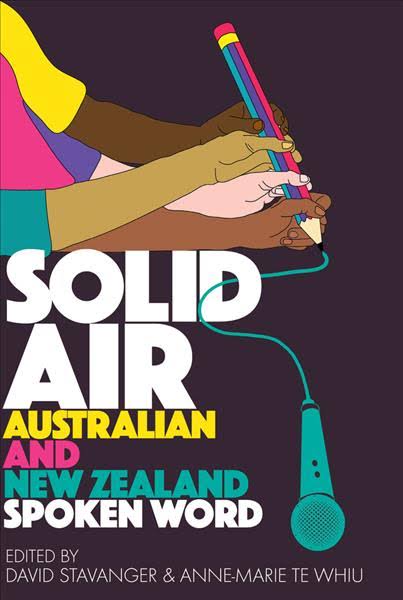

Firstly, a disclosure: I was chosen by the editors to perform at the Queensland Poetry Festival in 2017. I don’t appear in this anthology, though, so perhaps that balances any perceived bias. What Solid Air does so powerfully is remind us that poems involve positions, a precarious and essential bridging of sites, a profound resonance between bodies, such that the reader or audience is unavoidably implicated. The cover illustration by Des Skordilis is emblematic – four hands, of various skin tones, grasp a single pencil, whose lead becomes a microphone lead looming in the face of the reader. The opposite of siloing, this is a poetics of coming together, the potential for solidarity. Contrary to the image, however, rather than one microphone, the anthology contains 120 of them. And it’s partly in the juxtapositions of voice, not in any implied harmony, that this anthology makes its considerable mark.

There are the ‘big names’ expected by anyone acquainted with contemporary spoken word – Omar Musa, Maxine Beneba Clarke, Miles Merrill, Luka Lesson, Selina Tusitala Marsh – brushing up alongside emerging artists like Melanie Mununggurr-Williams, Jesse Oliver and Eleanor Malbon. Solid Air also takes a boldly expansive definition of ‘spoken word’, too, refusing the binary of ‘stage’ and ‘page’, including a great number of writers whose work confounds that outdated distinction – Nathan Curnow, Ali Cobby Eckermann, Quinn Eades, Omar Sakr and many more.

The selected authors are arranged alphabetically by surname, which means that Solid Air opens, entirely appropriately, with Hani Abdile’s ‘The beautiful ocean’, a breathtaking poem which somehow manages to hold the trauma of seeking asylum by sea within a refrain of love and survival. Immediately, Solid Air seems to be suggesting that the best ‘Australian’ poetry punctures holes – sometimes gentle, sometimes angry – in the idea of Australia itself. Behrouz Boochani, still imprisoned by the Australian government in offshore detention and denied citizenship, also appears in these pages, with a poem of longing and displacement in the midst of beauty.

Also appearing early in the anthology is one of the most exciting emerging voices around, Evelyn Araluen, whose ‘Fern your own gully’ lands with a thrillingly unsettling punch. The poem’s satire deconstructs ‘the smell of eucalypt’, ‘gumnut coins’ and ‘pastel bush dreams’ with fierce intelligence and a subjectivity that is both defiant and strategically elusive:

Just hop in that pouch, unusual girl

hop in the swag this whole home waits

in handpainted frames of silk native frocks

wear them to your reading

wear wattles from your ears

it’s all metaphor for the beautiful thin white woman

whose body slides linenly through bush

Resistance to colonialism – not only on the political and personal level, but in the idea of what literature is and should be – is a major theme in this book. Anahera Gildea, Te Kahu Rolleston, Grace Taylor and others from Aotearoa New Zealand fluidly integrate indigenous languages without translation. The casual disruption of English by these linguistic interventions is synecdochical – the words themselves standing for the ongoing embodied perseverance of all Indigenous peoples.

These juxtapositions feel more like mischievous channel surfing than any kind of straightforward argument. Araluen is followed by Ken Arkind, with his poem ‘Godbox’. With its long lines arranged vertically on the page, the poem is a jarring chorus of found prayers, numerous voices pleading in confusion, whispered despair and shouts of anger towards a deity who ‘will not answer’. The experience of reading it is shocking, visceral, tenderising.

Another poem driven by a prayerful refrain is ‘Tramlines’ by Arielle Cottingham, which riffs on the racialised implications of hair straightening and ‘straight-ness’ itself in the context of family and public ideas of beauty. To write such a thematic summary, of course, reduces the poem – it’s much more exhilarating and untamed than that, merciless in its honesty and how it implicates the reader. Here, the voice is capitalised, italicised, enjambed and run-on, so that its rhythms and pressures (both internal and external) are made acutely tangible.

These poems are not simply transcriptions of what is spoken. There are experiments with the space of the page that make a hesitant, stuttering or self-correcting voice concrete, but there are also elements here that can’t be understood purely in terms of the heard voice, but include a kind of unheard, internal voice. Emily Crocker’s ‘Spooks’ enfolds complexity into caesura and strikethroughs:

Glitching in the aisles, mate ah ma’am I knew I was a worryman when I began using my form as a flotation device, a skeleton key, a dustpan –

On a similar note, while to my ears Amanda Stewart’s poetry really does need to be heard, her ‘postiche’ allows a reader to experience the scrapes, slippages and ambiguities of her voice in a rigorous and playful page translation. Reminiscent of experiments with typewriters, but also of sound-artist DJs, ‘postiche’ manages to evoke late capitalism, surveillance and anxiety, without explicitly naming any of them.