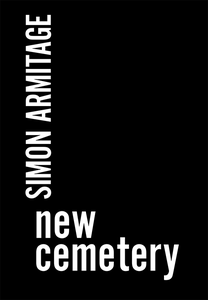

New Cemetery by Simon Armitage

Recent Work Press @ IPSI, 2016

Time in the Dingle by Philip Gross

Recent Work Press @ IPSI, 2016

Poetry has a peculiar provenance in the public sphere. To describe the situation with egregious simplicity, some allege that poetry should speak to and for the people, while others assert that poetry should be avant-garde, testing the conventions of language and enacting nothing less than a transformation of society. The demands we make of poetry – arguably more pronounced than of other forms of literature – were recently explored in Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry (2016), which argues that such idealism inevitably results in dissatisfaction with actual poetry. Poetry ends up not being accessible or representative enough, while the avant-garde poem, as Lerner memorably describes it, disappoints like a bomb failing to go off.

These reflections seem pertinent to a review of two chapbooks by the British poets Simon Armitage and Philip Gross, published by IPSI (International Poetry Studies Institute), a poetry research centre housed at the University of Canberra. The work of the Yorkshire poet Armitage, in particular, has been celebrated for its accessibility and popularity, while also being criticised for betraying the avant-garde poetic ideal. In 2013, Armitage was the third best-selling living British poet (after Carol Ann Duffy and Pam Ayres). That year, he also published a non-fiction book documenting a walk along the Pennine Way, during which he famously gave poetry readings in exchange for food and board, emulating the troubadours of the Middle Ages. However, his considerable skill as a poet has also been institutionally acknowledged by his 2015 appointment as Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, suggesting that, for some, Armitage’s poetry would undoubtedly not be accessible enough.

The author of over 20 poetry collections and numerous other works across different genres, Armitage has the reputation of being a ‘working poet,’ and New Cemetery is further evidence of his impressive professionalism. The untitled poems concern the construction of a new cemetery, which is memorably compared to the construction of a housing estate. It is an event that inspires reflections on the mortal body, as well as on the poet’s vocation in the face of such impermanence (in a way that echoes Heaney.) Each of the poems shows off Armitage’s formal assurance. I quote from the thirteenth poem:

Today the poet

repairs his shed,

last night’s storm

having scalped from the roof

some forty square feet

of weatherproof felt,

lifting and slinging the job lot

into next door’s field…

Armitage’s poetry is perfectly measured and typically distinguished, as here, by its outward gaze. The distancing use of the third person figure of ‘the poet,’ as in a number of poems in the chapbook, is interesting in this regard, refusing the autobiographical musing that render some lyric poetry obscure. (Some of Plath’s work comes to mind – though, interestingly, Armitage has named both Plath and Ted Hughes as key influences on his work, along with that other ‘popular’ poet Phillip Larkin.)

Armitage’s work is also known for its wit. In the fifth poem, the poet portrays himself working in an attic while it snows outside. An automatic sensor repeatedly turns off the light, due to the perceived lack of movement in the room. It is an episode rendered uncannily resonant in the context of a collection implicitly about death. The entire poem reads:

A cheap ballpoint

usually does the trick,

just enough drag and flow,

like this one, striped

with the faded name

of a Munich hotel.

Fine-grained snow

like old fashioned static

fell into the night, blanking

the tiled rooftops.

At the writing desk

in an attic room

I pushed forward, except

every fifteen minutes

a sensor detected

no movement,

no signs of life, and turned out

the one light bulb.

Philip Gross, like Armitage, is a prolific writer across various forms (from young adult fiction to opera libretti). Despite winning the TS Eliot prize (notably, when Armitage was a judge) and writing a book of poems about the concrete stumps of electrical pylons, Gross has, like Armitage, been criticised for writing poetry that is popular and therefore, by implication, compromised.

Time in the Dingle, like Armitage’s New Cemetery, is more accessible or ‘reader-friendly’ than some other works of poetry, but it is also far from facile, demonstrating Gross’s considerable skill with poetic language. Gross’s chapbook is a sequence of poems that centre on a local ‘dingle’ – a term the poet playfully defines in a poem called ‘Sounds’ (in which we see echoes of Hopkins and any number of contemporary lyrical ‘nature’ poets).

… I’ve tried cleft

cleave coomb chine for this sudden steep slip

of a strip of stray wildwood

into this crack crease interstices slightly

unpicked seam between breezeblock railing fence

over which, not quite concealed

by under-tangle, small spews of rubbish get spilled

as if over-the-hedge was outside-of-the-story

and into hiatus, the kind of between

we make with backs turned, where a place, a whole

order of things, might absent abscond conceal

itself under a word like

dingle – there, I’ve said it. Yap-dog in the leaf-mould.

We can call its name but it won’t come to heel.

The linguistic excess here distinguishes Gross’s lyrical verse from Armitage’s, even as they share a Romantic interest in environmental – as distinct from environmentalist – topics. There is also similar wit in some of the imagery. In ‘…or the squirrel,’ a squirrel is described as pouring ‘up a fifty-foot oak as if I’d spilled him.’ Another similarity: despite their shared working-class origins (often foregrounded in establishing their populist credentials), there is a great deal of ‘middle-class’ emotional restraint or ‘tastefulness’ in these observational lyric poems.

Will these chapbooks ‘change the world’? Probably not. There is much to admire and enjoy but little that is urgent here – though some of the other titles on the IPSI list (by Samuel Wagan Watson, for instance) offer different poetic models. Is this poetry that ‘speaks for everyone’? Probably not, given the complexity of some of the poetic language and diction, though the work of Armitage and Gross has proven relatively popular. Do such questions matter? In The Hatred of Poetry, Lerner recommends that we rediscover our love of actual poetry by reading poems without such idealistic baggage. It might be worth a shot.