Photo by Starkadur Barkarson

Since the inception of the Arts QLD Poet-in-Residence Program in 2005, we Queenslanders have reaped the benefit of an international poet spending three months in our state. Each poet has brought new perspectives, ideas and energy to the poetry community and some of them have helped reshape our (poetic) landscape. These poets / agents of change include Jacqueline Turner (Canada), Hinemoana Baker (New Zealand), emily XYZ (USA), Jacob Polley (UK) and our 2012 resident, angela rawlings (Iceland/Canada).

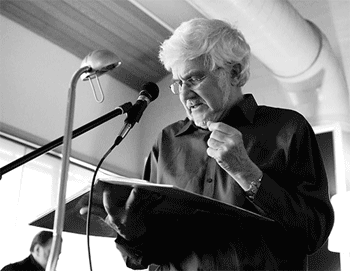

I had the privilege of working with angela rawlings in 2010 when she was an invited guest of QLD Poetry Festival. With that, I came into this interview with some insight into the wonder she could create on and off the stage, so when Cordite tapped me on the shoulder to do this interview, you couldn’t wipe the smile off my face. Now, having done the interview and again enjoying the privilege of working with rawlings, seeing her inject energy and wisdom into the community, it’s a smile that has only grown wider.

Graham Nunn: As the 2012 Arts QLD Poet-in-Residence, you had the opportunity to visit a number of locations throughout the state to harvest material for the Sound Poetry and Visual Poetry project that launched at Queensland Poetry Festival 2012. How did the idea for this project originate?

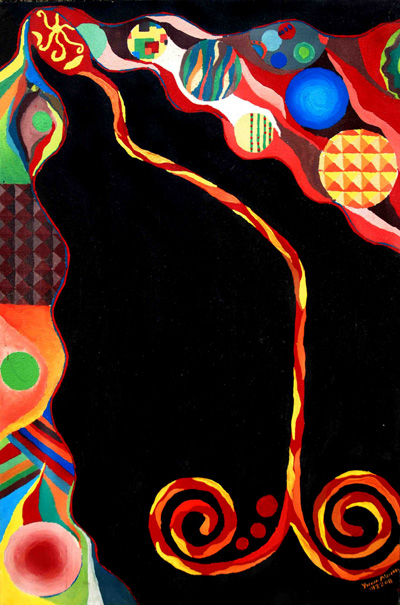

angela.rawlings: Since 2009, I’ve been developing Hjlóðljóð (translated as ‘Soundpoem’) – a prototype series for Sound Poetry and Visual Poetry based on Icelandic geography and language. Hjlóðljóð focuses on audio recordings of water, photographs of glass vials in Icelandic landscapes or with soundscape contributors encased inside of them and a physical collection of vials comprising the Hjlóðasafn (Museum/Library of Sound). While each vial has the capacity to recall a certain sound via synaesthesia, by and large the objects themselves are visual or tactile in their materiality. I was also learning my way through photography, so I moved from photographing landscapes and flora to photographing bottles in the moment of their sound-harvesting. For me, this replicated that moment when an unknown though communicative element becomes known through an act of identification, of naming. There was the landscape itself, the documented landscape, the documented moment of naming and then the naming itself (which existed beyond the photograph as a portable museum of sound).

An integral component of the project hinges on exploring notions that humans read their environments and/or that humans are in conversation with landscapes and inhabiting non-human species. Through Sound Poetry and Visual Poetry, my intention is to actively question embedded notions of what a (sound or visual) poem can be, what bodies (be they human, water, weather, other) are capable of or even constantly composing and how to ethically read, converse with or interpret non-human entities.

The position – with the title of Queensland Poet-in-Residence – has provided an opportunity to explore what it means to be a poet affiliated with, if only for a brief time, a large geographic region. How could the work I undertake create dialogue (and/or collaborate) with the land and inhabitants? How might I form a creative research project that would place me in a situation to interrogate my relationship with and ethical approach to an eponymous region?

GN: I imagine it is incredibly important to feel a connection to each of the places you visit, to be able to move beyond the surface and enter into a deeper dialogue with the land and its multi-layered history. I am eager to hear about your QLD experience and your engagement with the many places you visited.

a.r: The opportunity to visit Queensland for three months – immersed within bioregions completely unfamiliar to me – to develop new work has proven important for me. Similar to immersion in foreign human languages, immersion in foreign bioregions heightens my capacity to sense environments that are partly removed from the immediate superimposed semantics I have inherited. Looking at organic litter on a beach, I know little more than cursory titles like ‘leaf’, ‘shell’, ‘seed’. In the Daintree and, later, Magnetic Island, I was mesmerised by little balls of sand littering beaches as tides receded. It took two days of studying to eventually spot the heavily camouflaged crabs scuttling amidst those balls and into holes nearby them. The sand balls and their intricate arrangements indicated a deep logic at work, but one I was not equipped to decode.

Fauna proliferates in rural Queensland, so I was humbled to spend time near wild bandicoot, cockatoo, kookaburra, kangaroo, orange-footed scrubfowl, brush-hens, orb spider, blacktip reef sharks, cicada, huntsman spider, and platypi. Prolonged exposure to flora and fauna – beyond the glimpse of recognition and the fleeting moment of identification – led me through welcome realisations: ‘I may know a name given to you, but I do not know your name; I do not know you’ and ‘I may not know your name, but we’ll sit together and learn something of each other.’

While I was in Longreach, poet Helen Avery shared her family cattle ranch with me. The cows in-yard provided an incredible opera. Having grown up in rural areas, I’ve heard mooing before – but I’ve never listened to mooing. I spent a long while in close proximity with cattle, recording their polyphony. The experience surprised me, since I could not have anticipated that the soundscape of a cattle yard would become a seminal component of the project.

GN: For someone who has never experienced Iceland and its volcano and glacier-shaped landscapes, I am interested to know whether this project has uncovered any parallels; any similarities in the way these two unique places open up and speak?

a.r: During my second day of the residency, I met you and several other lovelies for lunch. As we ate, I noticed the word ‘ISLAND’ in a large font outside of a nearby building. At first, I read this as Ísland, which is the Icelandic place-name for Iceland. After lunch, we passed by the building and I realised that foliage obscured more text; in fact, it read ‘QUEENSLAND,’ but the bulk of QUEEN was obscured (except for the last part of the letter N). Somehow, the Iceland-of-the mind didn’t feel so distant at that moment.

I’m sure there are similarities – crossover species of birds such as terns, plovers, oystercatchers or that both islands have desert interiors and comparatively lush perimeters – but I’ve noted more of the differences. Iceland is a young country in geologic terms, while Australia is ancient. The flora and fauna that have evolved in Australia are at such different levels of succession compared to Iceland that it dizzies me. My greatest enthusiasm in the rainforest was viewing large epiphytes for the first time. Flora grows on flora here. By contrast, Iceland’s ecosystems are quite sensitive and have noticeably suffered from overgrazing. Trees cover only 1-2% of the island, and so the more common flora to see there is moss covering lava rocks, or grass fields, or introduced species such as Alaskan lupin.