Lyre by Stuart Cooke

Lyre by Stuart Cooke

UWA Publishing, 2019

Stuart Cooke’s Lyre is the most ambitious work of ecopoetry in recent years. Few other writers could be employed to embark on this kind of project either, I think, considering Cooke’s long engagement with the central questions of ecocriticism not only by way of extensive reading and writing in this field, but also with immersed fieldwork in diverse ecologies found outside Australian metropolitan and suburban zones: notably, the Philippines, Chile, and the West Kimberley. Lyre represents a high point in a substantial career devoted to a life of ecopoetry. The collection channels a career of attentive learning into striking, unpredictable ecotextual records, of the nanosecond-shifting foci of the firefly in flight, the stammering tremulant sonar of the Eastern Whipbird and the deep time shapes of Antarctic Beech distribution.

in the temperate forests, the wet

sclerophyll forests where tempests

moan in yourm leaves, a storm beating

muffled drums at the entrance

to the underworld, the lands

of Gondwana, motherland of Australia,

South America, the hundreds

of years creeping, the moss about youm creeping

‘Fallen Myrtle Trunk’

Lyre represents an ambitious realisation of a practice that in one sense has been the result of four distinct companionships with particular writer–critics: Stephen Muecke, Peter Minter, Michael Farrell and Martin Harrison. Companionships, more so than mentorships or influences, would no doubt be the preferable term for many of the parties involved here. And these companionships concern most of all shared ethical and intellectual commitments. Of course, there are countless more one could mention. Jerome Rothenberg is another key companion we should consider in Cooke’s ecocritical project, certainly as one of the first writer–critics to so engage in a poetics learnt from non-Western poetic traditions with the same degree of suspicion for the Western literary ancestry as Cooke employs. But fusing such contrasting yet companionable poetic trajectories is to also achieve something in poetry, at least, that has not looked like this before. No poet has so visibly digested the many alternative trajectories offered by these poets and thinkers into a singular practice.

These companionships signal a more influential body of thought than concepts of practice attributable to them. That body of thought is First Nations thought, most specifically Indigenous Australian thought, but additionally South American Indigenous, especially Mapuche thought. Muecke, Harrison and Minter have been channels to these epistemologies, Farrell a central collaborator in thinking about them, but Cooke has for some time now come to distinguish himself in a project of receptivity and learning with regards to these forms of knowledge.

In tune with the objectives of the postcolonial philosophical endeavour to return to cultural trajectories destroyed and distorted by colonisation, Cooke has shown decolonial attentiveness to contexts whose modes of thought and cultural authority have been poorly understood or integrated into visiting language practices through his own major studies in Indigenous language and thought. These studies have been best represented so far in Cooke’s work as editor of Nyigina lawman George Dyuŋgayan’s West Kimberley-based Bulu Line in The Bulu Line (2014), and in Cooke’s monograph on comparative Australian Indigenous and South American Indigenous poetics, Speaking the Earth’s Languages (2013). Cooke’s linguistic, philosophical and critical endeavours add up to a considerable resource for rethinking environmentally informed writing that tries to divest from the colonial–industrial enterprise.

While the vast majority of poems in Lyre do not make the achievement of earthly consciousness through political strategy per se, unlike the poetics of, say, John Kinsella, the book’s last poem, ‘Lake Mungo’, is an exception and, like Kinsella’s poetics, the poem’s remonstrances stem from the scandal of colonisation, with a heartfelt inquiry into the spirit of Mungo Man and Mungo Lady, names attributed to the oldest remains of Indigenous people discovered on the continent. This section of the expansive poem alludes to Oodgeroo’s ‘We Are Going’ in a key reversal:

[. . .] youm reveal

history’s carcass as yourm progress

youm reveal what descends

until futures unleash reversions

a Man and a Lady convene worlds, having been dispersed in them

they are returning, they will return

To continue reading the poem, as with the rest of Lyre, we must follow the line guided by textual kinesis, pattern and some of our own instinct, rather than follow conventional left-to-right, top-to-bottom consecutive flow. In fact, the following excerpt continues the line beginning ‘they are returning, they will return’ on the opposite page of the book, and thenceforward we clearly should read upwards to continue the flow starting from ‘stories in the land as we see it’:

the subtlety of Aboriginal time / the force of White settlement

in yourm lakebeds, dunes and sediments

yourm plants and animals, their evidence

stories in the land as we see it

So, this is the philosophical heart of Lyre. The book chronicles ‘organism’ in Alfred North Whitehead’s sense of it, as an immanent suborganization of a totality, something we see in Cooke’s willingness to base poems not only on birds and marine life but also ‘Mangroves’ and the ‘Shallow Estuary’. However, the principle has been learnt from Indigenous thought, that organisms generate their meanings, and that these epistemologies still prove obscured, ignored or misunderstood by a settler nation and polity. ‘Lake Mungo’ avows this influence and engages in an imaginative project with the discoveries of Mungo Man and Mungo Lady to allegorise it; the preceding poems activate the same project, but through an osmotic textual practice attempting to collaborate with the expressivities of nonhuman life as they seem to sound and dance through the page.

Following the decolonial ambitions of a nomadological, earthly journal-ism a la Muecke, a metamorphosed, archipelagic (and therefore post-national), ecologically informed consciousness a la Minter, a polyvocal repertoire of textual registers attuned to local alterity a la Farrell, and an entrustment of philosophical value in heightened sensory experience a la Harrison, Lyre presents the most sustained effort in recent memory of an ecopoetics that combines textual experiment and wild earthly experience in such dynamism.

Lyre does not present the landscape-wandering phenomenologies we are familiar with in the ecopoetry of, say, Louise Crisp or Peter Riley. Such poetry’s experiential motion explores new phenomenological mobilities inspired by earthly contact, and tends to mean visual, cartographical results. In Cooke’s case, in line with the posthuman becoming theorised in Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy and presented in Cooke’s opening epigraph – ‘writing as a rat draws a line or flicks its tail, as a bird casts a sound, as a feline slinks or sinks in sleep’ – the result is a transformative and sensory textuality. Both phenomenological and posthuman approaches to ecopoetry have their comparative appeal; the former is invested in the embodied experience of the environment while the latter is in trans-subjective intensity. Consider Cooke’s ‘Satin Bowerbird’ chronicle, remembering that such a bird should mean some of the most visual delights of the avian world:

yourm lamp’s intense licks of lilac

full blue-black in yourm seventh year

or it swerves and collides with the leaves

pours over youm, seeps into youm

seal shape, sealed slick, light

youm build scene with yourm

black root, lure of scene

splayed azure from its sleek

yourm anatomy spills into art

Not merely visual, the sensory palette of the passage considers architectural, chemical, erotic, haptic and aural qualities also. As such, the practice continually strays from conventional single-voice-centred phenomenological orientations found in lyric poetry, or vignette, so-called objective approaches influenced by modern technology, such as Imagism. While Cooke cannot entirely refrain from the temptation of imagining what some of these organisms think and feel – it is only human – mostly in Lyre tremendous patterns of footfalls, swish, flutter, scamper, explosion, bluster, blaze, flower and furl shape the page-overflowing behaviour of unruly life.

Lyre represents a multi-modal effort to bring logics of environmental relation into textual play that seem to motivate the gecko’s shifting attention, stir the air with the compound utterances of magpies that network their communication systems, or even explain the despondent laziness of an idle cat in the afternoon. Achieving less in terms of the descriptive, existential or political means for the urgent need to improve humankind’s sustainable intimacy with nonhuman life – the prominent poets past and present in this line from this continent include Lionel Fogarty, Judith Wright, Minter and Kinsella, and Cooke hardly resembles these stylistically – Lyre realises an unlikely itinerary of vibrant ecospheres, mammalian, marine and volcanic, that continues a complementary project to such necessary poets in a new vein.

This use of ‘yourm’, and ‘youm’ later in the quotation – obviously meaning ’your’ and ‘you’ respectively – seems puzzling, but in my understanding represents a desire to estrange pronouns from their linguistic invisibility to English speakers and thereby bring attention to the a priori function of human subject identification within this language, especially since saying ‘you’ refers in many of these cases to nonhuman subjects; that is nevertheless what we do in English – attribute others, whether human or otherwise, with ‘you’ when referring to them. It appears then that Cooke wishes to estrange that invisibility of the pronoun and so too alert the reader to the act of naming in the encounter with others.

To Gather Your Leaving: Asian Diaspora Poetry from America, Australia, UK & Europe

To Gather Your Leaving: Asian Diaspora Poetry from America, Australia, UK & Europe Modern English Poetry by Younger Indians

Modern English Poetry by Younger Indians Lyre by Stuart Cooke

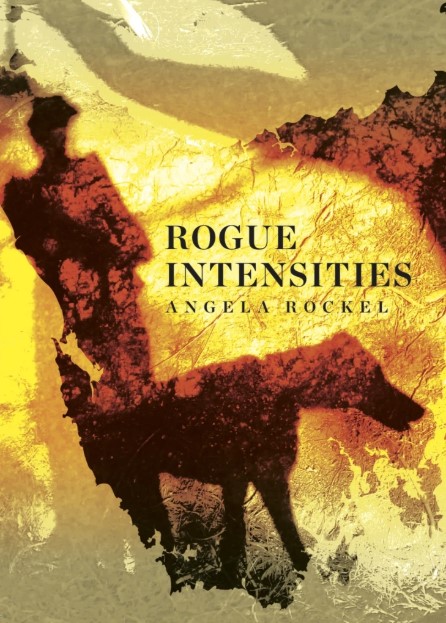

Lyre by Stuart Cooke Rogue Intensities by Angela Rockel

Rogue Intensities by Angela Rockel