blur by the by Cham Zhi Yi

Subbed In, 2019

‘I have always advocated: adding, adding and adding cultures and languages instead of literally eliminating them in the name of a pure identity.’

The reader will have to imagine for themselves what Maria-Àngels Roque, editor-in-chief of Quaderns de la Mediterrània, a twice-yearly journal focused on authors from the Euro-Mediterranean, must have felt upon hearing these words. The sentiment belonged to the bisexual Spanish novelist (and scabrous critic of its society) Juan Goytisolo. Through the multiplication of languages, cultures, and viewpoints, Goytisolo sought to honour his birthplace’s Moorish and Jewish roots, and the long-suppressed influence of Arabic on the Spanish language. The project formed part of a broader mission aimed at undoing the strictures he inherited as a child growing up in Franco’s Spain: a stifling admixture of fascism, Catholic monotheism, and heteronormativity dubbed nacionalcatolicismo (Goytisolo credited the phenomenon with having given Spain a ‘long holiday from history’). He made his modus operandi even clearer ten years earlier, talking to Maya Jaggi for The Guardian:

The vitality of a culture is in its capacity to assimilate foreign influences. The culture that’s defensive and closed condemns itself to decadence. […] When I was a child in the 40s, the Catalan language was forbidden. I realised that to have two languages and cultures is better than one; three better than two. You should always add, not subtract.

Published last year, and receiving the 2019 Anne Elder Award, Cham Zhi Yi’s debut collection, blur by the, is informed by linguistic heterogeneity. Like Goytisolo, Cham employs a combination of languages and styles, raising questions about who speaks and who is spoken to. They question what it means to write your identity when others have already presumed to try to write it for you (even in a reductive and brutally essentialised form). For writers who have not traditionally been included in the Western canon, the problem is one of narrativisation and self-recognition; of always having to wonder whether you are the protagonist of your story, or simply writing against a colonial frame. As Cham observes:

i tell people to call me zhi. but

truly my heart swells when

my mother says me whole

i want to know this joy daily

but cannot bear

the affliction of a name

Cham’s poetry is founded in the interstices of her birthplace (and its Malay-Chinese inheritance) alongside the cultures of her adopted home (Ngunnawal, Ngambri, Ngarigu, and Canberra-based settler). She often makes connections between eating and migration as a way of exploring multiple cultural affiliations. Indeed, food functions as a useful metaphor for Cham’s entire practice: a substance that breaks down boundaries between internal and external, living and inert, essential sustenance and surplus pleasure. It also affords Cham an opportunity to demonstrate her keen eye for food’s detail and gauzy tactility: in the poem ‘colonisation 2 ways’ eggs are ‘white pepper bleed yolks/edible Pollock’.

At times, the food/migration motif can risk seeming like a familiar trope (although a large part of that problem lies with how food has been received and marketed locally, where it is made synonymous with a certain kind of liberal settler tolerance and cosmopolitanism). Farrin Foster recently wrote for Kill Your Darlings about how MasterChef’s latest season (internationally syndicated in 86 countries) has become a paradoxical source of soft power for Australia; one in which ‘A viewer in Port Moresby could conceivably be served this online ad demonising immigration to Australia, before switching on TV to see MasterChef contestant Khanh Ong speak emotionally about coming to Australia as a refugee.’ Although the presence of food in blur by the is perhaps closer to a source of sensual pleasure, a way of connecting with home, Cham also signals an awareness of how it may be received by a settler audience. During ‘let me by survived by loneliness’, a meta-authorial voice interrupts the connections Cham draws between hunger and nostalgia to speak directly to the reader:

when i wake i set about cutting & bruising anything that bleeds tears

cook everything that stings

begin eating a meal that will satiate my hunger before it does my nostalgia

put away the leftovers

call ma

ma i am wanting. i am wanting to go home. let home be as simple as proximity to you.

home need not be Swatow

– & because this poem is for a white audience let me clarify Swatow is the city in Guangzhou where generations ago my family was ‘from’. before australia. before malaysia. & generations before Swatow we must have been from elsewhere but my longing for this specific city stems from a fantasy: that no one in Swatow ever asked our ancestors ‘where are you from?’ –

Caught between the dilemmas of identity in Swatow (and it is worth recalling that the ‘swa’ or ‘shan’ (汕) of ‘Swatow’ refers to bamboo fish traps: the city was a fishing village during the Song Dynasty), Cham finds

despite my location my ancestors

all their trades their tongues their gods & their ghosts be my legacy

remind myself i am many

Subtle gradations of typographical colour serve to anchor the poet’s sense of liminal space, drawing attention to the way those less visible aspects of cultural inheritance might be limned on the page:

when did white arrive on the shores of time?

she too has been colonised

expel white from spine

let it be ash

But is the success of the colonial – and, by definition, assimilationist – project simply a matter of pragmatic acceptance on the part of those colonised? A resignation to the idea that material circumstance and exigencies demand adaptation to the dominant culture? And if so, what does the poet do with the redundancies that emerge from that acceptance? In a culture as determinedly (yet falsely) monolingual as Australia’s, the poet necessarily finds some part of themselves denied a voice, a purchase on a distinct identity. Dedicated to Naarm-based Oromo poet and artist Saaro Umar, Cham laments, in ‘post-Solange’,

what else am i to do. with

this moist southeast asian mouth

withering here

in the southern hemisphere

edge of split-fraying

loosening seatbelt like

ready to disembark

from this face

now that ive stowed away

four of my five tongues for winter

what else are they to do with me ?

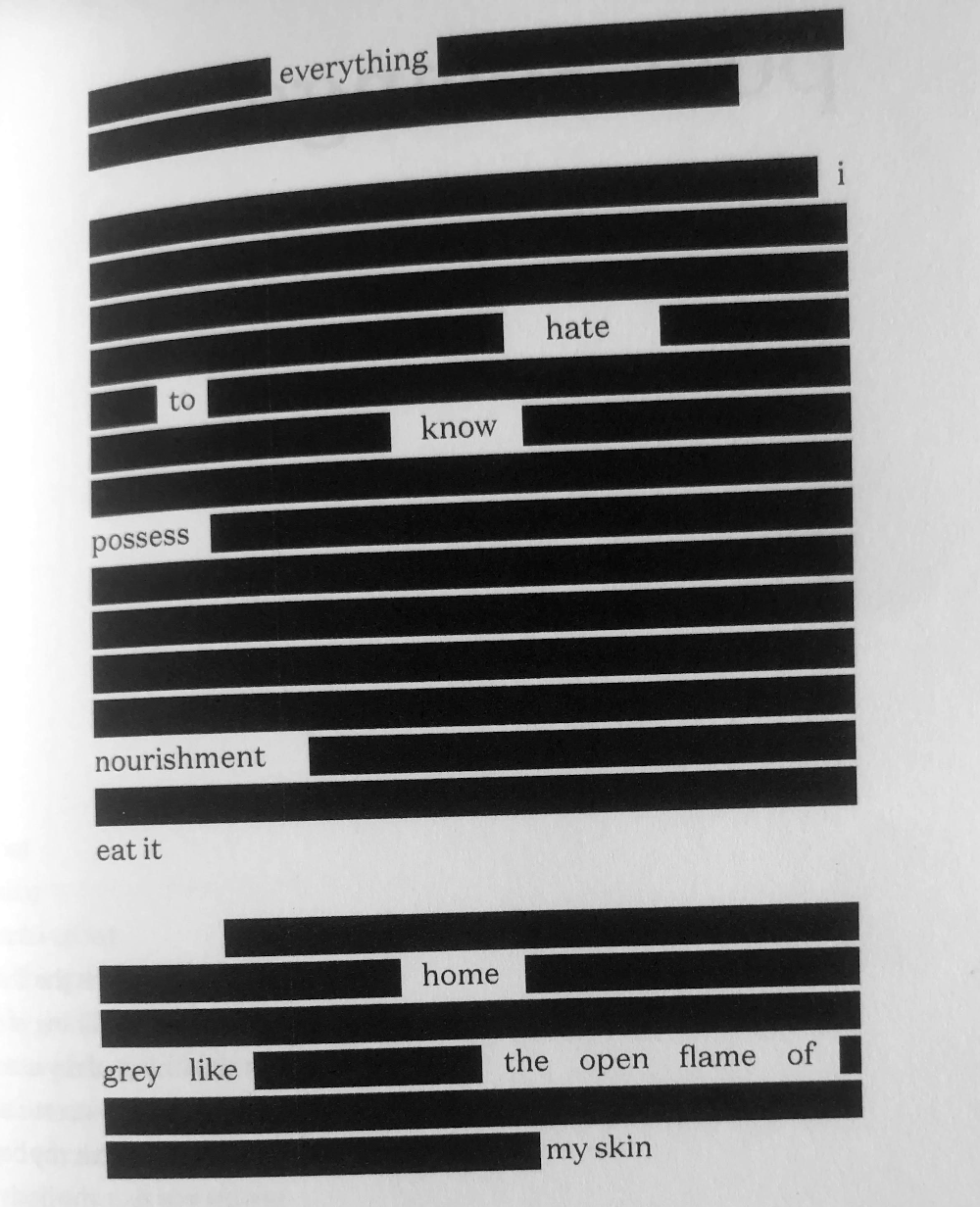

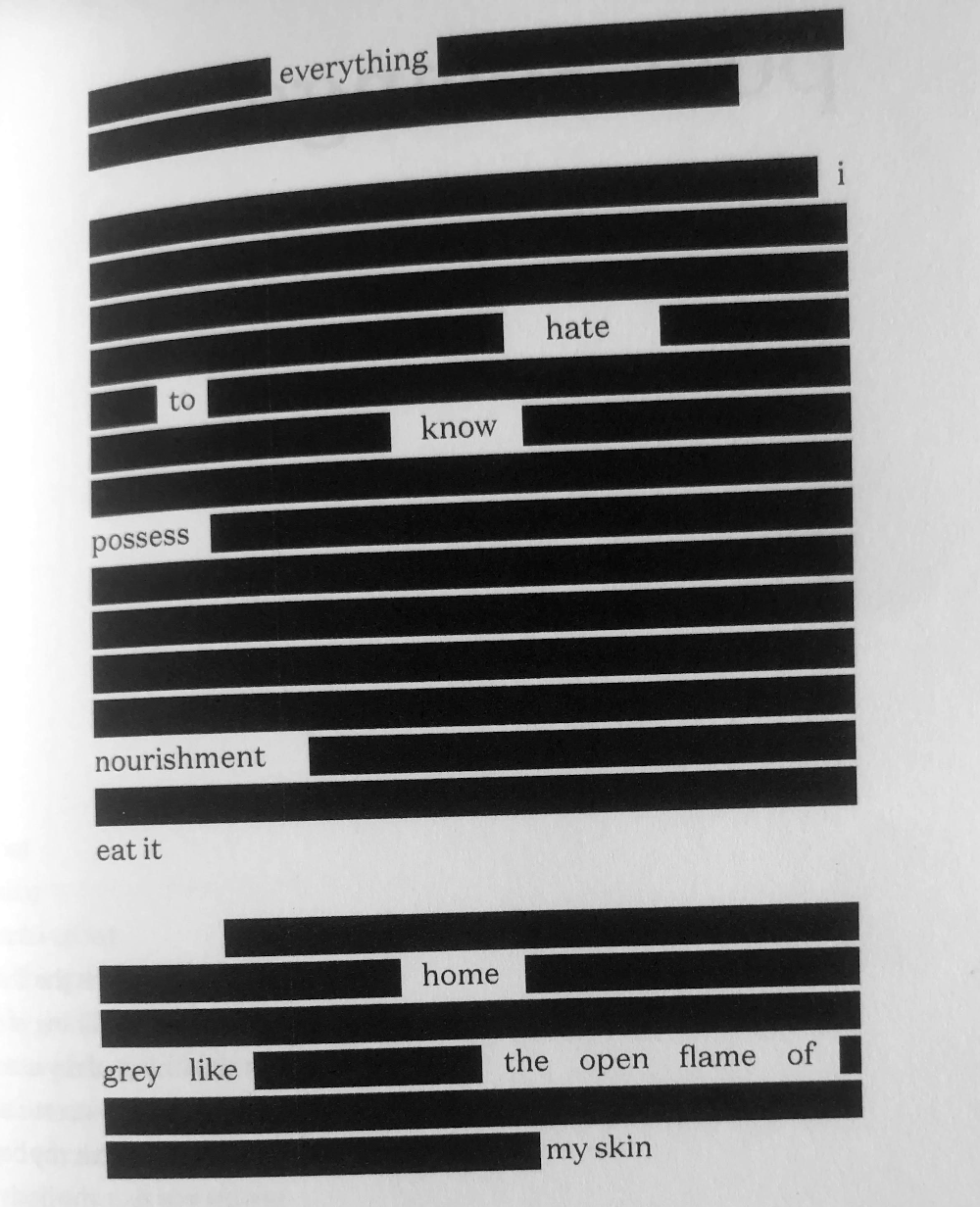

The ‘Untitled’ sequence of poems shows how this abbreviation, the four of five tongues stowed away for winter, might be rendered visually legible. In ‘Untitled 1’ various words are blacked out. For ‘Untitled 2’, most of the poem is erased (and, had the pattern continued in this fashion, ‘Untitled 3’ might have simply been once large vertical black box; instead, different phrases are omitted). Occasional words surface like stray light, capturing the sense of self-permission described in ‘be sure we aren’t dreaming’: ‘allow myself/the mourning of redacted history’. The sequence is especially notable for drawing attention to what is missing – a kind of clarified erasure:

What you see is what you get; and what you get are those caesurae and absences that compose and structure poetry. It represents a kind of meta-working, a demonstration of how the poem (Here’s one I made earlier! ) is constructed. By rearranging the intercessionary redactions throughout the sequence, the poem assumes different readings, while leaving the reader to guess at what the initial gaps might signal.

The Empty Show by Alice Allan

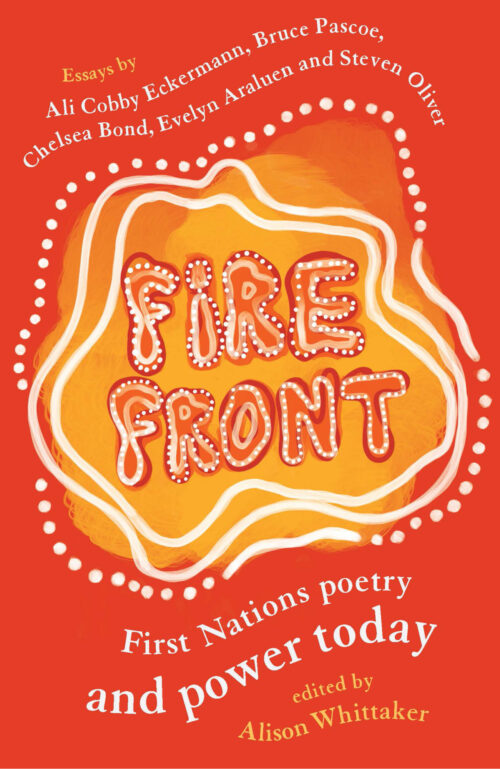

The Empty Show by Alice Allan Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today

Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today

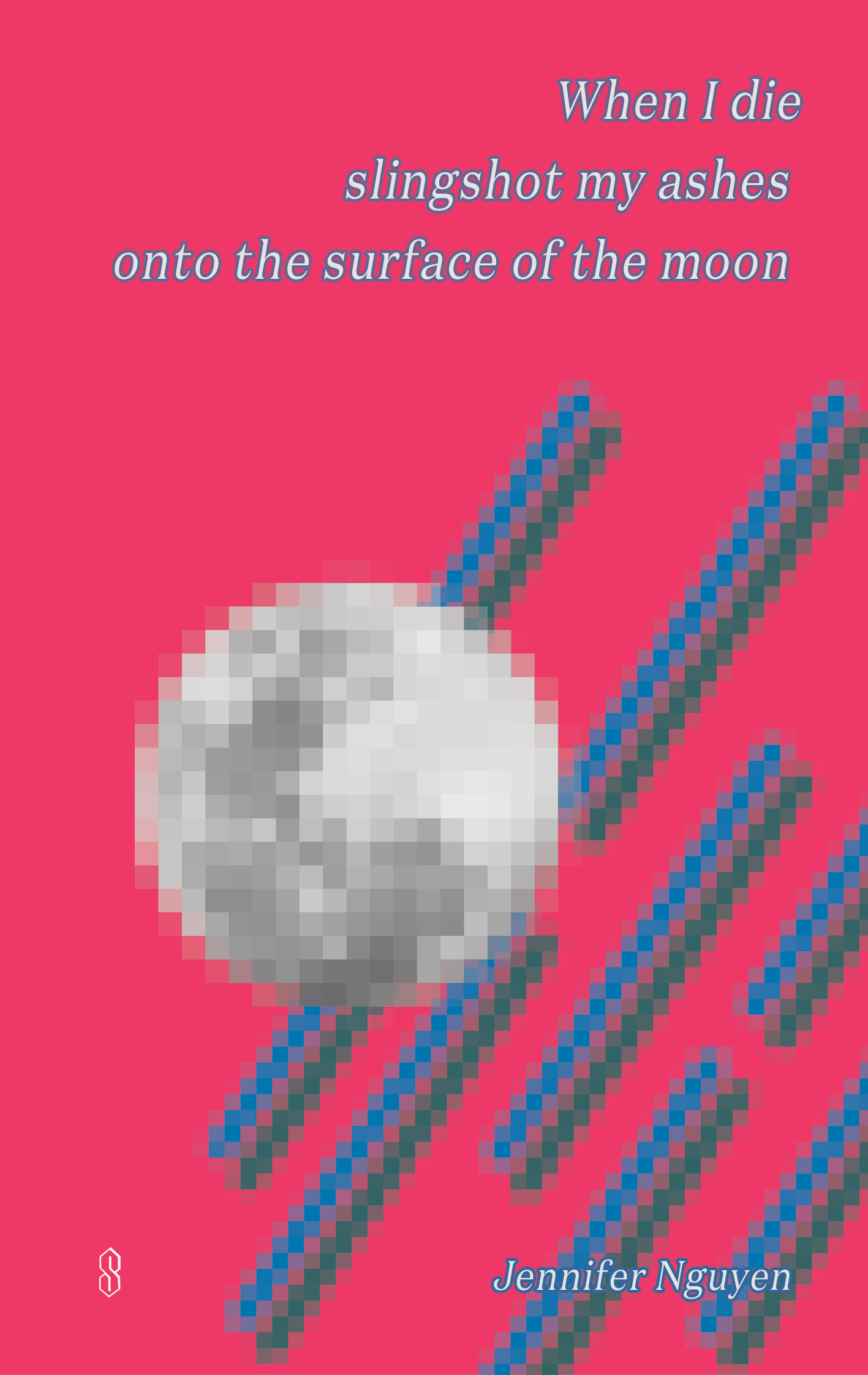

When I die slingshot my ashes onto the surface of the moon by Jennifer Nguyen

When I die slingshot my ashes onto the surface of the moon by Jennifer Nguyen Noonday by Ursula Robinson-Shaw

Noonday by Ursula Robinson-Shaw

Timestamps by Sofie Westcombe

Timestamps by Sofie Westcombe Sweatshop Women: Volume One

Sweatshop Women: Volume One