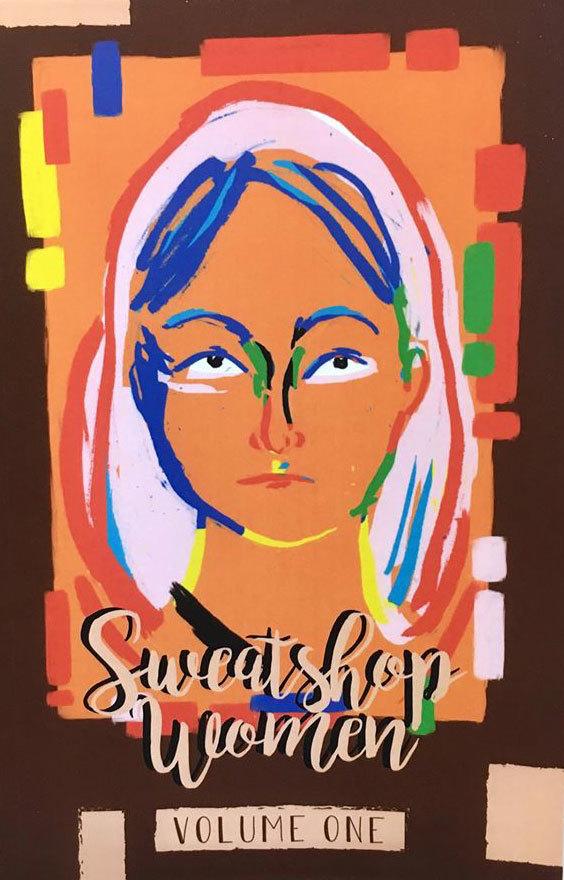

Sweatshop Women: Volume One

Sweatshop Women: Volume One

Edited by Winnie Dunn

Sweatshop, 2019

Sweatshop Women: Volume One is an anthology of poetry and prose by twenty-three emerging writers based in Western Sydney. As a text, Sweatshop Women unapologetically claims space in the public archive of literary testimony crafted on this continent by women of colour. Equally, I can’t help but regard this anthology as more than simply the text itself. After all, Sweatshop is a self-professed ‘literacy movement’, a community arts initiative providing local literary programming for creators of colour in Western Sydney. Naturally, the anthology is grounded in this function and purpose. From mentorship, to editing, to graphic design of the work and, of course, the writing itself, Sweatshop Women asserts the right of women of colour to exercise autonomy throughout all aspects of sharing their voices and stories, and facilitates an opportunity to do so. This is a more generative place for my mind to meet this work: in first acknowledging the process and practice of bringing a publication like this together, and the work of initiating relationships, opening to the communal and individual (un)learning and risk-taking that community arts practice entails. In her introduction, editor Winnie Dunn references the writers of this anthology as ‘the collective’, describing their monthly workshops and crediting guidance from established writers such as Randa Abdel-Fattah, Roanna Gonsalves and Alison Whittaker as formative in its creation. Within the settler colony of so-called ‘australia’, gathering emerging and established women artists of colour together to think critically, speak and share freely and take ‘charge’, in Dunn’s words, of representing themselves is important and meaningful work, though not without challenge and complexity.

In this work, I am transported to local community celebrations and family gatherings, quiet and contemplative moments of grief and loss, Islamophobic job interviews and school visits, suburban hangouts and raucus childhood disputes. While styles and forms of writing included are broad, there is a pervasive sense of groundedness, attentiveness and intimacy throughout the collection, magnified by the confessional and interior nature of many pieces, which sit in an ambiguous space between fiction and memoir. Themes of cultural assimilation, coming of age and finding a sense of balance between belonging and autonomy among family and community take various shapes. One of my most cherished motifs (both in life and in this anthology) emerges early on: migrant elders and their beloved fresh produce! Lieu-Chi Nguyen’s vivid ghost story ‘The Long-Boobed Ghost’ is populated with scenes of grandmothers and aunties who vigorously suck lychees and rambutans, sitting peacefully among fruit pips as they share in gossip and instruction. Shirley Le’s short fiction in ‘Vietnam Still Remains Vietnam’ meditates on her mother’s love of mandarins, ‘IMPERIAL’ stamped, a humble vessel through which to consider the colonialisms of her homeland, and the present-day Australian colony. Such meticulously told short stories brush up against the enigmatic, bold free verse of Jessica Wendy Mensah’s poetry in ‘Tracing Our Waist Beads’, whose rhythm and emphasis I crave to see amplified in live reading, with its heavy use of capitalisation — ‘I’M BLACK BAKED!’ — and thunderous, Ṣàngó-imbued imagery of ‘black rain’ and raging weather. Mensah weaves together subtle yet striking histories of migration of Yoruba people from Nigeria to Ghana — ‘Yoruba packaged their empty souls into cubed boxes’ — and now to a suburban setting where the ungodly ‘Women’s Weekly falls’. Mensah’s work is a stark outlier in comparison to the three remaining poems of the collection: ‘Dirty White’, ‘Best Little Brothel on Parramatta Rd’ and ‘Spice Mix’, which exhibit a much more explicitly narrative approach and remind me of the often vulnerable ways narrative storytelling and poetic form might merge at an open mic night filled with free verse, and interior reflections.

The stories and poems of Sweatshop Women weave deftly between Dharug land — with its recurrent ‘white fibro houses’ signifying Sydney’s Western suburbs — and elsewhere, as we follow storytellers’ familial lineages abroad, through travel or memory. Unsurprisingly, these writers’ attentiveness to place is one of the collection’s strengths and pleasures in reading. The first lines of Monikka Eliah’s story ‘Bethet Dinga’ open like a map to reveal the epicentre of her tale, an example of the care taken throughout the collection to orient readers within shifting settings.

The first house I remember was on Jabal Amman — Mountain of Amman. It was in the first circle, an area marked by eight large traffic spots spread out along the main street named Zahran.

Another contributor, Claire Cao, subtitles the halves of her short story ‘Going to Kuan Yi Temple’ according to the soil of the suburbs she writes of: part one, ‘Cabramatta Dirt’ and part two, ‘Canley Vale Dirt’, which I learn are neighbouring yet distinct. I find myself on Google Maps on more than one occasion, seeking visual confirmation of locations already precisely described. Much of the collection is lightly punctuated by scenes at local train stations, schools, public and community spaces such as Yagoona Station, Bankstown Girls, Belmore PCYC. As a non-local of any of the domestic or international locations described, I lack experiential knowledge and connotation of my own regarding these places, and I’m sure many subtleties wash over me. I imagine for any Western Sydney locals, Sweatshop Women presents a series of winding paths, diverging and converging again, down many of which will be familiar landmarks, establishments and scents. Recognisable to those who know, a kind of insider intimacy lies inherent within these writers’ approaches to space and geography.

The plight of the Third Culture Kid who inhabits a liminal space between the culture, time and place of their parents, and that of their own surroundings (whether in childhood or now grown) is a thread that runs throughout this text. I find that much of the most evocative and deftly handled writing of Sweatshop Women occurs in the interactions between parents, elders and those who have come after them. The warmth, care and often impatience which marks mothers’ interactions with daughters are carefully recounted. ‘Mumma knows every path through my hair,’ is a soft and graceful line from Raveena Grover’s story ‘Frizz Witch’. In ‘Wall of Men’, a young woman holds her breath after hearing her mother speak openly about the patriarchal violence she experienced in her first marriage, reciting from a deep well of heteronormative advice, ‘I tell you to be careful. The man you choose is the life you choose.’ The sombreness of this revelation continues to infect the tale, which moves on through acidic humour and unabashed, cheeky exploration of the young protagonist’s sexual and romantic desires. In Naima Ibrahim’s short story ‘A Curse and a Prayer’, a Somali mother is devastated when her son returns home with his ear pierced, distressed that it will be interpreted by other parents and elders in the community as a reflection of inadequate parenting. Though unwilling to remove the earring, the gentleness of her son’s response is evocatively described, and the complicated terrain of intergenerational relationships, religion, gendered cultural expectations and mental health within communities who have survived war, exodus and relocation is delicately evinced:

I couldn’t help it. I started to cry. He wrapped an arm around my shoulder, his clumsy boy hands held mine tight. ‘It’s okay, Hooyo.’ These breakdowns had become common in the last few years. I’m still not sure why.

I’m entranced by Ibrahim’s succinct ability to capture both the sense of emotional intimacy and dissonance between mother and son in this vignette. This story excites me as another nuanced local voice broadening representation of African families in the full vulnerability and personhood systematically denied us.