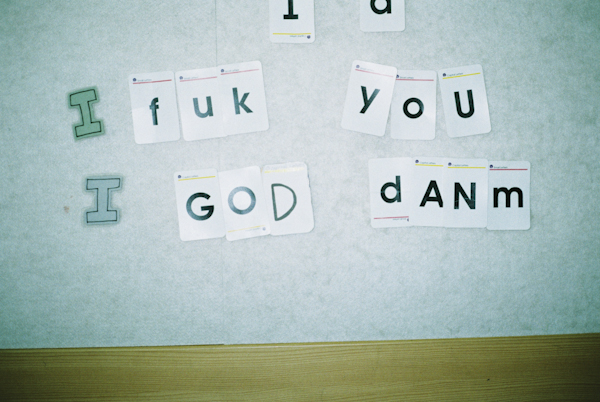

Pattern recognition algorithms only give us ‘fuzzy’ matches,

eschewing the exact in favour of the textual, or else the sublime.

This text, then, serves as a warning that “Oz-Ko”, the present

object of study, is not an object at all – rather, an attempt to trace,

using machine translation and serendipity, the metamorphosis

of tiger into bear. In fact, there’s an app for that, like most things.

The opening screen locates the user inside a terrace house,

the kind that students used to occupy in the early nineties but

which is now a facade for something else, something bigger.

Just like Agent Orange, the evening descends without mercy.

Once inside the zone, you experience strafing runs that paint

oil on air, feel the shock and awe. There are Australians here,

fighting both for and against the Koreas. Post-apocalypse,

some sing nesting songs, in voices filled with the quiet hope

of reconstruction, while others write poems without mothers,

or texts hollow and sad. In a perfect evocation of melodrama,

looking to the south, we see the compass points have switched:

convoys perform thirty-eight-point turns, crossing the Han river

and driving north. Having reached the old Mintongsun Line

we exit the vehicle and buy a couple of energy tonics from the

conveniently-located convenience shack/PX. The young guy

serving us grins at our grey watches, or our Antipodean tans.

The sign says something we cannot read or understand. This

is only to be expected: we begin from a position of ignorance.

For example, it takes a certain kind of person to interpret that

sign as saying Do not feed the lion when there’s no zoo for

miles and the strokes country cries out for sustenance, rains.

Nothing much surprises anymore. That’s the way of cliché.

It sounds familiar when you travel back to the world made up

by that White guy in Voss. The sky becomes blue as a new

Renaissance, internet explorers ride URLs through the desert,

the hooves of their camels pressing hyperlinks into the sand,

while faraway Laura tweets the sudden rain in Tilba Tilba.

Between these two imaginary notions – the Oz and the Ko –

lies an interface of skin, a winding path of dim calculations.

You don’t meet many anthologists along the way but then

again, you hadn’t expected any. The sound of the old bark

peeling away from the trees holds you captive, makes you

wince. You have no names for any of these trees, either, so

you concentrate on the farmhouse instead. Ants crawl over

your hands and make jagged patterns. There is an old canal

that’s teeming with carp. They, like us, have been imported,

shipped in barrels and bred in tanks. Let them loose in stolen

rivers, introduce them to the peace pagoda’s ponds. We see

smoke rising and experience some kind of volcano meditation.

Out of water, we suck in the still-free air, to no avail. It would

take more than the tricks of an everyday magician to save us

from our own planned obsolescence. Again with the arrogance:

if attacked by a shark, blame the shark. When travelling in a

strange land, hate the strangers. And don’t forget to take some

photographs and post them on your blog. Come on now, we’ve

all been caught calling Korea at some stage. But who are we?

Is your history, when it comes down to it, just a blog entry with

no previous post? Okay, this sounds pompous, but then so do

many poems when read out loud. Are you a member of the new

carless generation, or does your life revolve around road trips,

the cinema strips of tar? Pity the bus drivers outside Tongdosa!

Stuck there for hours at a time while the tourists seek Buddha!

Does this sound familiar? What is this place at which we think

we’ve arrived first? How can we go out to be in time, when

our moments collapse into memes, instead of correspondence?

Tiring of the narrator’s rhetoric, another poet pens five sijo for

her raider. Noting that the plural of sijo is also sijo, all the sijo

in the world merge into a single sijo, just as all the coastlines

you have ever known eventually turn into one big empty road,

or a wave. Suddenly a bagnier pulls you from the surf, saving

your modesty as much as your life. You peruse the next slide:

a view from the memory in which we try to kiss each other.

The border guard inquires as to your state of origin but you’ve

left your passport behind in the burning village. Similarly, two

sisters found at the central railway station in 1907 were unable

to provide identification; just three years later, their country was

annexed. Recycling the possible proves to be the only option –

but how? The wind says it is not possible. The buildings swaying

like trees scream “Don’t be stupid” and sound like they mean it.

Apparently healing is harder to practice than it is to recommend.

Still, your survey of bearded men produces startling results; in

fact, several journals are interested in publishing them. It’s all

very well to talk about translation studies but aren’t the gaps

between what make language and communication really interesting?

The next slide, a view from the Yarra Bend with two men, stops

that train of thought in its tracks. Maybe this is just as well. After

all, it’s midnight and the convenience store is closing in an hour.

We’ve been here once before, although the context was different:

you were running after Hwang Jin Ye. We bought Pocari Sweat

because it was humid outside and the bottle mentioned something

about ion supply. I was compiling a book of lepidopterists’ anecdotes,

entitled Colourful Moths of North Korea. Some things you just

can’t make up. A Host is an organism that harbours parasites. Yes,

true. It says so right here in Wikipedia. You pulled out a notebook

and penned a paean to the God Skype. After that, we decided to

go shopping. The malls were all open, and the smoky street stalls

looked inviting as well. Eventually we chose a Korean triptych:

silkworm larvae, sundae and beers. Strangely enough, they didn’t

sit too well together in our stomachs, and we lurched towards the

subway entrance crying Aa-zaa-dee!, which has no meaning here.

According to The New Scientist, North Korea could make two

nuclear bombs per year. At that rate, No-Ko will be the world’s new

superpower in 4550, give or take a decade. Nevertheless, as old

Gough Whitlam might have said, It’s Time, It’s Time to dust off

the stereotypes once more, to reduce an entire culture to puppets.

Or just one puppet … Students know the drill: copy, photocoffee

Till the library closes! Nick Cave may be popular in Seoul but

we just can’t tell yet. Do you know what “Here’s To The Regular

Air Force Korea” is really about? Tell everyone what you think.

Ah, “Mea Culpa”. That was just the Internets, stalking my bad.

A double abecedary on tertiary teaching sounds like trouble.

Extra points awarded to students who can render said abecedary

in four dimensions. There’s that temporal ghost again, sprawling

on the footpath outside the HQ like an exhausted cyclist, crying.

The compass point swings north again, like a turnstile in reverse,

or a screen-printer’s squimjim, or a crème brûlée. Young people

are sitting in cafeterias, not following instructions. Fall in love.

Do it now. That’s an order of magnitude for you. Take a number.

Languages that were never spoken where “I came from” sound

beautiful and dangerous to the ear. In the mouth, they taste just

fine. Is this it? The zero turning into one? Call it an approach, an

invitation. Just don’t pretend you came here for enlightenment.

The Swan River is central to Perth’s mythology. It’s the proverbial lifeblood of our township. If we were feudal, we’d bring our horses to drink from it, our children to learn the magnitude of life it contains. Of course, now our river blossoms algae, and we move from feudal to almost futile. As settlers, we have disrupted the mythology Indigenous Australians birthed it with. We have even accidentally pumped it full of effluence, the foreshore attracting its own sense of chaos and grand uncontrollable beauty. And yet, it still captures our imagination, although we are watching it die.

The Swan River is central to Perth’s mythology. It’s the proverbial lifeblood of our township. If we were feudal, we’d bring our horses to drink from it, our children to learn the magnitude of life it contains. Of course, now our river blossoms algae, and we move from feudal to almost futile. As settlers, we have disrupted the mythology Indigenous Australians birthed it with. We have even accidentally pumped it full of effluence, the foreshore attracting its own sense of chaos and grand uncontrollable beauty. And yet, it still captures our imagination, although we are watching it die. A Whistled Bit of Bop by Ken Bolton

A Whistled Bit of Bop by Ken Bolton Best Australian Poems 2010 edited by Robert Adamson

Best Australian Poems 2010 edited by Robert Adamson The Elephant in the Room

The Elephant in the Room I’ve been swimming since I was two and the feeling it gives me, of such wonderful lightness, is approximated by nothing else on earth. Except maybe alcohol. As adulthood came and passed me by I indulged in liquors that lifted my head two feet above my body and by waving my arms I could follow it up into the air. My drinking has always had a very narrow purpose, one that I’ve repeatedly given up without issue or pain; it is a bonus to rather than a facet of my days. But when I moved to Seoul I was confronted with a type of drinking attitude that insisted my commitment to alcohol be put to the test. For the first time I was taking part in a night life that had no half measures, no flip side to the coin: it’s go for a drink or go to bed. And if you choose bed, you’d better take a drink along.

I’ve been swimming since I was two and the feeling it gives me, of such wonderful lightness, is approximated by nothing else on earth. Except maybe alcohol. As adulthood came and passed me by I indulged in liquors that lifted my head two feet above my body and by waving my arms I could follow it up into the air. My drinking has always had a very narrow purpose, one that I’ve repeatedly given up without issue or pain; it is a bonus to rather than a facet of my days. But when I moved to Seoul I was confronted with a type of drinking attitude that insisted my commitment to alcohol be put to the test. For the first time I was taking part in a night life that had no half measures, no flip side to the coin: it’s go for a drink or go to bed. And if you choose bed, you’d better take a drink along. Sand by Robert Drewe and John Kinsella

Sand by Robert Drewe and John Kinsella Mommy Must be a Fountain of Feathers by Kim Hyesoon

Mommy Must be a Fountain of Feathers by Kim Hyesoon