From 'The Twentieth Century Never Happened' (2010) NZEPC

What I write, as I have said before, could only be called poetry because there is no other category in which to put it. – Marianne Moore

1. ‘Poetic Art’

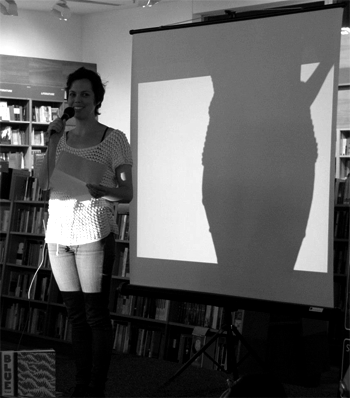

Sydney poet Amanda Stewart is one of the most technically accomplished performance poets living in the country. Writing and performing since the 1970s, Stewart remains ‘contemporary.’ She appears, significantly, in Pam Brown’s Jacket2 anthology ‘51 contemporary poets from Australia.’ Suitable designations for what Stewart is would usually be something like ‘multimedia’ or ‘intermedia’ poet, sound poet, or poet and performance artist. Narrowly avoiding Dick Higgins’s useful term ‘intermedia’ for the sake of clarity, in this article I have chosen another term: ‘poetic art,’ to describe the work of Stewart and, from a distant but nonetheless related milieu, the American poet, visual artist, and composer Anne Tardos. I chose to use the term poetic art in place of ‘intermedia art’ simply because, as I see it, poetic art better describes the metonymical quality of the particular kinds of work they do. Poetic art might be defined as poetry which is not simply poetry but also art, and not even just art; a practice which attempts a ‘generalised ekphrasis’ across the boundaries between mediums while considering its main business to be that of poetry. What manifests as poetic art has its own rich history.

There are, necessarily, variations and differences between Stewart’s poetic art, which lives at the cusp of both conceptualism and procedure, and Tardos’s poetic art, which is procedural and performance-based. What binds them, however, is an interest in inaugurating ruptures at the edges and ‘betweens’ of certain sign-systems, using a range of methods, machines, processes, and practices. What I will describe as ‘xerographesis’ (the photocopy poem) pushes this ‘generalised ekphrasis’ into much more drastic territory, where the terms of the poem itself are emptied out – along with the poem’s objects – under the sign of poetry.

2. Universal Ekphrasizing: Anne Tardos’s Among Men

One of the key terms that will need to be spoken of in approaching the idea of poetic art is the rhetorical term ‘ekphrasis.’ There is some significance in the fact that ekphrasis has traditionally occurred – regardless of how wide a net we draw for the term – from the standpoint of poetry. Operating as a kind of receptacle among the arts, the ekphrastic poem awaits the intrusion (or intersection) of another art. Attempts – fruitful ones – have been made to shift the ‘centre’ of ekphrasis to another art. One of the most notable efforts is Siglind Bruhn’s shifting of the ekphrastic centre to music in her works on ‘musical ekphrasis.’ Bruhn shifts the ekphrastic ‘noumenon’ from music to poetry. Consequently, musical ekphrasis means ‘composers responding to poetry and painting.’ Does this disturb the main function of ekphrasis? It seems not. To experiment: if we take James Heffernan’s commonly rehearsed definition; ‘the verbal representation of visual representation,’ reduce it to its common denominators, and then factor in the hybridity of interartistic exchange in ekphrastic practices, you get ‘the representation of representation.’ Before each representation you might substitute any of the multiple types of art: ‘sculptural representation of musical representation,’ ‘painterly representation of verbal representation,’ and so on.

What remains intriguing about ekphrasis, then, is the more universal, general, and functional aspects of its use across multiple mediums, more than claims of an originary (and perhaps mystical) connection between two specific mediums per se. For poetry, this is significant in an American, post-Objectivist context. Let us take a well-known example: the relation between music and poetry in Louis Zukofsky’s integral function (upper limit music, lower limit speech). Is it not easy to misread this as simply evidence of the ‘compossibility’ of terms within interart contexts? Does the asymptotic nature of the equation not simply serve as an indication of the (productive) impossibility of full transposition or translation between arts? One should take Zukofsky literally, here. Of the two limits of Zukofsky’s integral, Mark Scroggins writes that ‘while they may be asymptotically approached, can never be reached.’ That is, poetry can never quite be definitively just speech, and neither can it be definitively music, no matter how close it gets to either.

Forming the final part of ‘A’, Zukofsky’s lifelong long poem, ‘A’-24, composed by Louis’s wife Celia Thaew Zukofsky (otherwise known as the L. Z. Masque), represents this point of ekphrastic impossibility. As Rachel Blau DuPlessis has suggested, it forms a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork encompassing several or all the arts). The four spoken-word parts of ‘A’-24, using language from Zukofsky’s poetic oeuvre, are superimposed on or weave amongst Handel’s harpsichord pieces, resulting in an almost unperformable and unreadable collage. The point is, in one sense, that the hybridity of multi-media work will always lead to failure, to blurring, occlusion, or even incomprehensibility. Nonetheless, it must fail in order to do its work. This occurs generically and universally as a function of ekphrastic, interart contact. While genres are ‘not to be mixed’ (in Derrida’s sense), artists of whatever sort are abidingly attracted to the (il)legality of genre-crossing, mixing, and interference. No one art holds a special place at the centre of all the arts, but instead each art taxonomically concatenates with another, in a kind of roulette, moving around and at various points holding the centre.

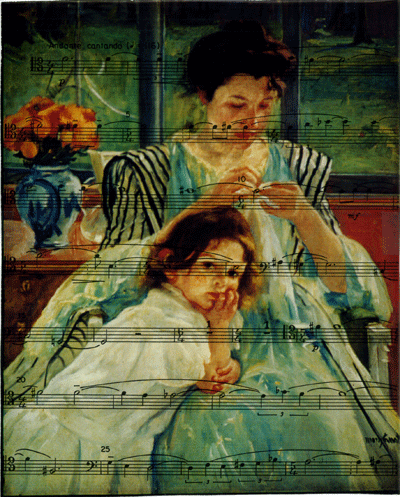

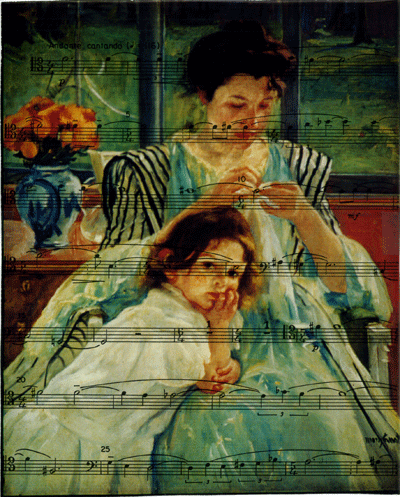

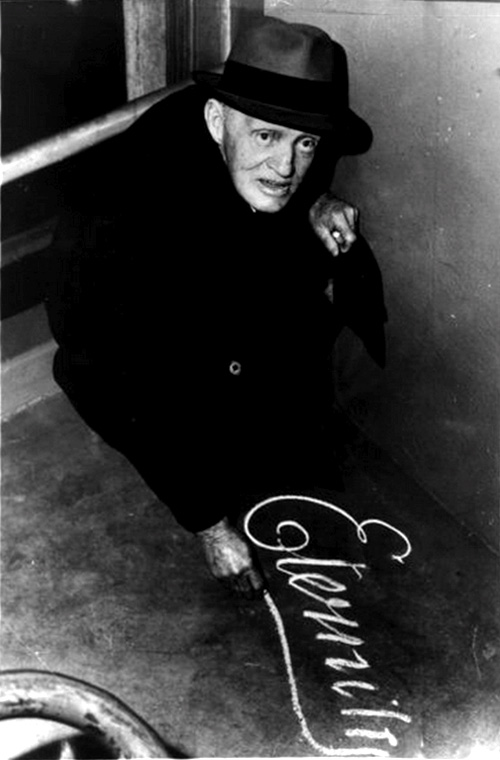

This model can explain one of Anne Tardos’s most intriguing works of performable poetic art, Among Men (1994). Several of the images for Among Men appeared in her book of poems The Dik Dik’s Solitude: New and Selected Works, published by Granary Books (also a publisher of artist-books) in 2002. Among Men is a ‘multimedia performance piece’ for up to nine instrumentalists, four voices, and seventeen slides. Like ‘A’-24, it brings together a variety of mediums, but it does not attempt anything like a Gesamtkunstwerk. It is a ‘piece,’ standing alone as an object, yet not unpleasing to the ear. Though the visual element is important, listeners will get the sense that Among Men is composed to be heard. For the instrumentalists, the procedure is as follows: ‘instrumentalists perform scores created by superimposing transparencies of paintings and sculptures over excerpted musical notation. The instrumentalists play the notation as modified by the superimposed artworks.’ Tardos further explains how she ‘copied the music, and then carefully selected each sheet to fit under each of the transparencies. Parts of the music, clefs, entire lines, etc. had to be cropped to fit the images. I mounted them together and returned to the copy shop. There I made laser copies of each “sandwich.”’

The relation between music and painting here is simply that they must go one on top of the other. With the aid of a photocopier, musical scores are superimposed on paintings. This superimposition, in turn, generates the performance, its visuality scores and overscores the sound. Each art ‘sees through’ and indeed, intrudes upon the other in a kind of breaking through the surface of score and paint, paint and score. Though Among Men is deemed fit to appear in a book of poems, its general ekphrastic treatment of material and performance – and its impulse to gather, inseminate, obstruct, and block neighbouring arts – distributes its artistic work across three domains: painting, music, and poetry.

Anne Tardos, from ‘Among Men: Musicians Scores’ (1994). annetardos.com | Accessed 27/03/12

3. Analogous Music

Hazel Smith, comparing Stewart with contemporary Australian poet and poetic artist Ania Walwicz, notices that:

In Amanda Stewart’s performances there is a much greater gap between the text and performance than in Ania Walwicz’s work. The texts have a visual interest of their own which is often transformed into an aural effect, though it is not always the only aural effect one would most expect.

Not so obvious at first, this disjunction between text and performance becomes a crucial integer in Stewart’s poetry and thought, especially in understanding her relation to the letter. Keep in mind the radical manifestation of this in the way Among Men was to be performed (reading whatever notes are not obscured by the superimposed painting). For Stewart’s poem ‘phoneme,’ as I read it, speaks clearly to the collagistic, object-oriented nature of her attitude to the aural and performative dimension. In particular, how aural effects, or the poetic ‘music,’ seem to emerge from (or break through) the surface of text, and how visual interest transforms (or transposes) to aural effect. The poem reads:

music is how

we first remember

each thought carries the ruin

of a sound

the mouth

breaking the surface

This is a poem about music, and the thinking of thought in that relation. It is an astonishingly concise and yet suggestive poem. Articulation breaks the surface. Thought breaks through the sensuous surface of phonemic layers, leaving the ruins of sound. Or, one could disregard the enjambing of ‘remember / each thought …’ to uncover some of the associations of the singular ‘purity’ of music and thought. Zukofsky writes, in ‘A Statement for Poetry’:

music does not depend mainly on the human voice, as poetry does, for rendition. And it is possible in imagination to divorce speech of all graphic elements, to let it become a movement of sounds. It is this musical horizon of poetry (which incidentally poems perhaps never reach) that permits anybody who does not know Greek to listen and get something out of the poetry of Homer.

By no means was Zukofsky advocating phonocentrism. He was speculating on a curious paradox: the ‘musicality’ of poetry, or the ‘resonance’ of poetic form, is what draws poetry towards the impossible horizon of music. It is precisely the same dynamic that occurs in other forms of ekphrasis, like visual ek-phrasis: poems that go after paintings with talk. Poems never quite reach the painterly horizon (poems never quite become paintings). In ‘Poetry Ideas,’ Stewart’s own statement on poetry, we hear:

But I do have my own voice. It is located in the collage, in the points of juxtaposition in the arrangement of sounds. We become creatures of imitation. We are not. Breath, pause, pitch, volume are very important in the poems

Voice, for Amanda Stewart, comes to life via visual terms (collage, juxtaposition, arrangement). One makes one’s voice, but it is nonetheless your voice, or at least your choice of voice. As far as music and speech are concerned, Stewart’s configuration of voice marks a critical difference with Zukofsky’s. This can be detected also in Smith’s observation about the gap between text and performance in Stewart. Listening to Stewart, at a certain point speech is emptied of its referentiality. It becomes, so to speak, an analogous ‘music.’ Like the musical sign-system, in its relatively (but not entirely) non-referential condition, Stewart’s vocal sign-system metonymically shadows music’s. So, to summarize very briefly: the poet need not divorce speech of all its graphic elements. The voice is a collage tool that re-arranges and juxtaposes its sonic objects.

From this, we can prepare a reading of her Xerox art, or what I term ‘xerographesis,’ where Stewart presents a radical limitation to the aforementioned notion of generalised ekphrasis. This mode of ekphrasis was concerned primarily with the collagistic collapsing or convergence of art forms. In contrast, xerographesis reduces what we know of the poetic to the very barest of means and empties it out to the negativity of both its visual trace and its graphic subtraction. Xerographesis, I claim, radically reverses form into itself. Should the poetic artist dedicated to ekphrasis participate in this ‘breaking through the surface’ we would have before us some of the first signs of the writing of ‘xerographesis’, and of the universal or general ekphrasis it both inherits and expels.

4. Xerographesis

‘But it suffices to listen to poetry, which Saussure was certainly in the habit of doing, for a polyphony to be heard and for it to become clear that all discourse is aligned along the several staves of a musical score’.

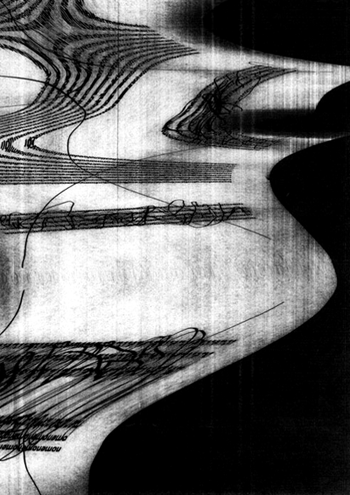

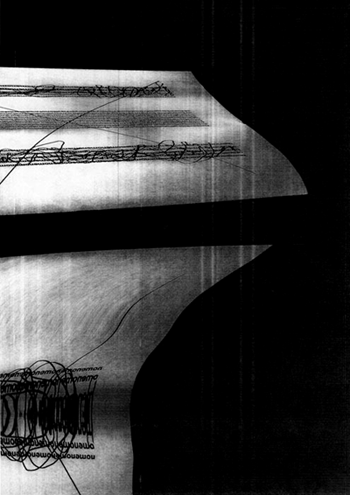

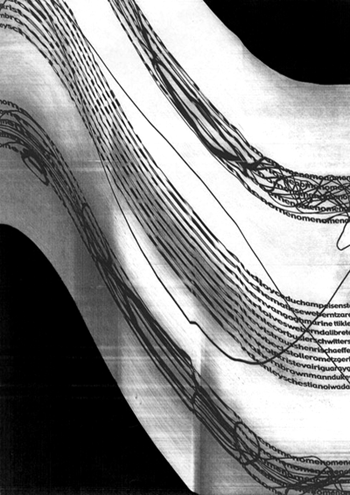

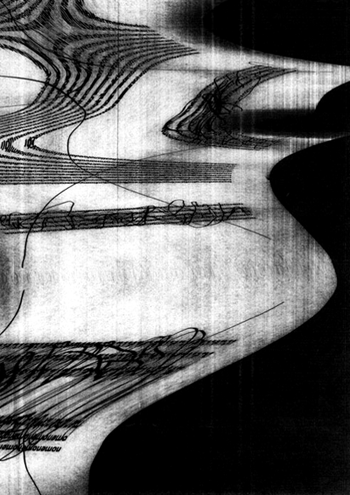

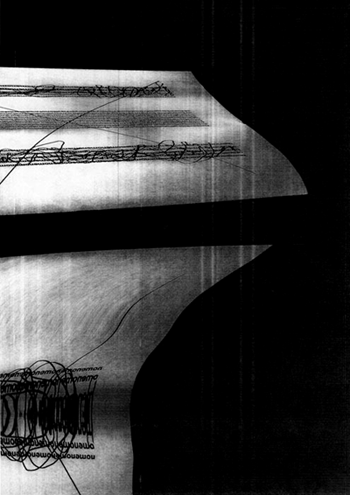

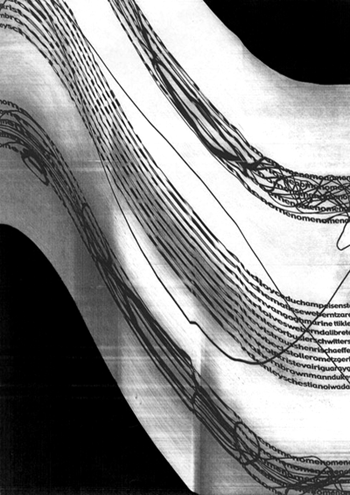

Marie-Rose Logan defines ‘graphesis’ (drawn from the verbal root grapho, ‘to write,’ and ‘grapheme’ [the written object]) as the ‘nodal point of the articulation of a text.’ It is in this mode that I read Stewart’s use of the Xerox machine in ‘Photocopy Poems.’ There is a cinematic element in their articulation. A motion. Stewart uses the photocopier’s toner as a means towards the photo-grammatic ‘freeze-frame’, performing the surface of the page by submitting its sensuous properties as object to the movement of the image in time. Two of the photocopy poems Stewart published in the online poetry journal ekleksographia bring this to light. We see the words stretched out almost as if they were becoming staves on a score.

If meaning is generated by the stillness of the page against the movement of the scanning eye, what would it mean to install the toner as a proxy eye? Here we would have the subjective movement of the paper, by the poet’s hand, against the stillness of the toner’s static gaze. Less than a simply subjective account of the gesture, a poetics of xerography introduces a visibility of time brought about by the reversal of roles given to the object. In this case, the gaze becomes an object: the toner looks. The meaning of such a reversal says something about the surface of the page as it acts upon the static surface. What does it mean to have an eye that does not move, that stays put as a landscape or a text shifts in front of it? Stewart, in her xerographesis, her photocopy ‘writing’ does the equivalent of vocal inflection for speech: she inflects the toner with a polyphony that at times resembles a musical score.

From 'The Twentieth Century Never Happened' (2010) NZEPC

From 'The Twentieth Century Never Happened' (2010) NZEPC

5. Xerox Objects

In her poem ‘absence,’ Stewart writes that ‘the act of observation becomes the object itself.’ This discernibly Lacanian approach to the object and the gaze can be traced through her work. Objects in xerographesis occupy a unique status. We are not left with a ‘synthesis’ of the sonic and graphic, but rather a disjunction, a jarring. Ella O’Keefe writes:

… the various components of Stewart’s works, whilst being inextricably interrelated to one another, do not strive to make sense of the other. The poems that straddle graphic and sonic field of inscription do so in order for language, and our varied ways of experiencing it, to be interrogated … Often in I/T the edges of sonic and graphic fields pull apart when language becomes less recognisably itself, existing as a memory or premonition, an inarticulate mark. Stewart’s ‘Photocopy Poems’ are the result of language that has been repeatedly processed through technology (the photocopier) so that the shapes we are left to examine can only be an imprint, a warped photogram that makes neat print into ambiguous light and dark forms. ‘The Photocopy Poems’ are the after-effects, the excess, of language in use.

Or, instead of writing on the page, warping the photogrammatic freeze-frame over the toner’s surface turns the page itself into a writer. Yet Stewart is not so much concerned with the collapsing of, say, sonic and graphic boundaries, so much as exploring the mistakes, inconsistencies, or excess of their combination. Against collapsing as such, excess becomes the defining factor in her use of language.

One thing is clear. It is a strange use of language, pushing language to the edges, but not quite off. We are left with the excess, or trace, of the literally performed word. Articulated in a sensuous region between process and the object, that is, by testing the sensuousness of the worded page against another flat surface (the toner), this work operates on a principle of articulation that performs the sensuous properties of real objects. To further illustrate this, I want to focus now on section from Stewart’s longer poem ‘ICON’. In the Selected, it is published (to great effect) beside one of her photocopy poems. This poem, as I read it, takes the lost object as its point of departure, or ‘subtraction’, through the image:

7.

the movement throughout the image

of body, whole, gathered and real.

begin. end. sense.

like a likeness, a sign, the ritual,

repeat. To focus becomes the object

is disappearing.

It suffices. An Astronomy of power,

implicit, subtle, carnivorous,

bureaucracies serenade their untied shoelaces

not being able to

possess:

not being able to

(I/T, Selected Poems, p. 50)

What is the thought and the effect of this poem? A reader could imagine she is describing the process of making the Photocopy Poems. ‘To focus becomes the object/is disappearing.’ Forming a sentence, these lines ‘subtract’ the object from its real presence, like the eidetic writing of the toner. The writing’s curvature is exacerbated on the one hand by the sensuous properties of the object (the writing on the page that writes both sensuously and without sense on the toner) and on the other the real object (the original writing on the page), which escapes possession, and representation as such. What is left is certainly a trace, but a trace of the perceptual emptying-out or subtraction of the object in its disappearance, leaving its negative imprint.

6. On the Political Aesthetics of Xerox

… I copy and copy

and copy, dead paper

flies out like dry tongues, craving

the art of a poem you want

about peace.

[. . .]

. . . It’s a choice

of no choice, this art in me

that wails . . .

— Doris Safie, ‘Meditations by the Xerox Machine’

Previously I have suggested that it is a certain approach to medium that signifies poetic art as poetic art, and allows, in a metonymic turn, what would usually not be called poetry to be called poetry. But within what specific situation can Stewart’s experimental praxis of poetic art be understood? For Stewart, we must include America as an important influence on her work, particularly her role in the aesthetics and politics of the group ‘Machine for Making Sense’ in the late eighties and early nineties. In an excellent interview with Sydney poet Astrid Lorange, Stewart cites her American contemporaries as highly influential:

Chris [Mann] and I both knew John Cage and Bob Ashley, Annea Lockwood, Phill Niblock, Richard Titelbaum, Kenneth Gaburo, Jackson Mac Low and Anne Tardos. Some of these people are no longer with us, which is really sad. I remember our tours in America so fondly, because people were so responsive to what our project was and that generation of people who are in their 70s and 80s and 90s now I just found absolutely mind-boggling. They’d come through this incredibly rich period of culture. I felt so fortunate to have engaged with that. And although I wouldn’t say that we were directly influenced by any of those people, of course, indirectly they’re part of the substructure of our being as well: the wonderful tradition of American composition and writing.

To compare Stewart with Tardos makes sense both historically and in terms of their shared versatility with medium. This transnational context gives credence to the shared attitudes and practices that make them poetic artists. Given that Stewart cites poets who are all outside what Charles Bernstein calls ‘Official Verse Culture,’ we may surmise that their shared poetic artistry forms a nexus in a countertradition of experimentalism and procedure in the US poetry scene of the late 20th Century. Not simply poets, and not simply artists, their work operates on a principle of formal transposition which dominates the work under the situation of more than one art (music, visual art, poetry) and thus signals the generality of their ekphrasizing. Xerographesis, or ‘xeropoeisis,’ on the other hand, presents a radical departure from this practice.

For Jacques Rancière, the key connection between politics and aesthetics is what he calls the ‘distribution of the sensible’ – that which ‘establishes at one and the same time something common that is shared and exclusive parts.’ For Rancière, it is not only the interface between different mediums (say, the concinnity between the flatness of the page and non-representational painting), but even something as general as connections forged between poems and their typography, that generates new forms of life and politics. To be a political reader we must be attuned to ruptures in the logic of representation, or clear instances where there has been a drastic reconfiguration of given forms of perception. This does not immediately signal a direct correspondence between aesthetics and politics, but is simply to say that we can read politics into the distribution of formal practices, commitments and differences. For this reason, the poetic art of xerographesis, the articulation of written forms on the toner, and the radical reversal of writing itself in the subtraction of the written object from its trace, has to be recognised as politically significant. But what about Sydney, Stewart’s immediate context? Lorange writes of her encounter with Stewart in the Jacket2 interview:

Stewart was sympathetic to my intuitions about Sydney, and the way the city seems to lose, or lose track of, its materials. She felt that there was something about Melbourne that supported a culture and ethos of documentation, whereas in Sydney there was a tendency to forget, or misplace, its emissions. I told her the slant of my project, emphasising that the recovery of materials need not be an exercise in nostalgia, it can be a process of construction, where new relations of arrangement support new methods for dealing with material in the first place. She obliged by digging through her bookshelves and talking through memories, relation to relation.

It could be said, for those familiar enough with the city, that Sydney fears the sensuous life of its objects – the ‘staling’, going-off of its materials. Or trash. As many of my generation would, I remember still the thrill of visiting the tip as a child. I remember scores of dis-used objects, the tin cans, soggy teddy bears, magazines, and shredded sofas … all at the edge of visible memory. To wit, Sydney has taken the removal of rubbish-removal to mind. These are legitimate complaints about Sydney’s relations to its objects. And this would be as much a criticism as simply a sounding out of the situation art finds itself in Sydney, or more generally in commodity capitalism. But Stewart’s collagistic voice welcomes the duration of objects as they puncture time in their appearance and linger in their disappearance. By paying close attention to the sensuous and shifting surfaces of objects through the coalescence of technology and language, the poetic artist dwells on the excess of material, on the shadow of truths left behind from the perceptual and sensual disappearance of objects.

7. Truth, Appearance, Articulation

According to Alain Badiou, truth in poetry is both a power and a powerlessness: ‘The mystery is, strictly speaking, that every poetic truth leaves at its own center what it does not have the power to bring into presence.’ While in the scheme of these ‘inaesthetic’ readings Badiou is not at all advocating outright realism, we can read here the absent thing, the absent object of the poem, as the beginning of the procedures of the poem’s truth. Referring to Mallarmé, for Badiou the poem is ‘centered on the dissolution of the object in its present purity. It is the constitution of the moment of this dissolution’ (Handbook of Inaesthetics, 29).

Emptying the image of its object, and subtracting the object from the image’s movement, both the photocopy poems and ‘ICON (Part 7)’ seem very much to agree with this calculation. By itself, hybridity does not produce poetic or artistic power. If the articulation of truths remains at the crux of Stewart’s feminist politics and poetic language – and I think it does – her procedural xerographesis shows how truth, and the objects of poetic truth, can be made visible via their dissolution. Nodding to the Hélène Cixous of The Laugh of the Medusa, some lines from Part 5 of ‘The Truth about Bisexuality’ articulate these truths:

the feminine,

becoming, becoming,

always in future, always

a sum, absence squared,

on the tip of the tongue, appearing

(I/T, p. 24)

Pairing the making-visible of appearance with ‘absence squared,’ feminine becoming is ‘always in future’ – an event to come. Why squared? Exponentiation in language? A future, surely, in the ‘patheme’ of language. On the tip of the tongue and at the edge of language, writing, and articulation in speech, her becoming is a jouissance of the feminine. Not lack so much as excess. A becoming also in which the truth of bisexuality, of horizontal bonds in sexual difference, cannot be separated from the objects that define it by virtue of their dissolution. That is, in their withdrawal from the visible.

Andrew Carruthers, Sydney 2012

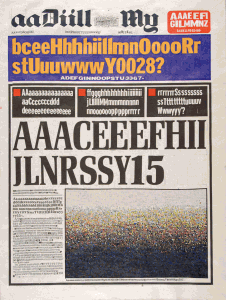

With surgical blades and a meticulous hand, Kim Rugg dissects and reassembles newspapers, stamps, comic books, cereal boxes and postage stamps in order to render them conventionally illegible. The front page of the LA Times, for example, becomes neatly alphabetized jargon, debunking the illusion of its producers’ authority as much as the message itself. Through her re-appropriation of medium and meaning, she effectively highlights the innately slanted nature of the distribution of information as well as its messengers. Rugg has also created hand-drawn works alongside wallpaper installations, both of which toy with authenticity and falsehood through subtle trompe l’oeil.

With surgical blades and a meticulous hand, Kim Rugg dissects and reassembles newspapers, stamps, comic books, cereal boxes and postage stamps in order to render them conventionally illegible. The front page of the LA Times, for example, becomes neatly alphabetized jargon, debunking the illusion of its producers’ authority as much as the message itself. Through her re-appropriation of medium and meaning, she effectively highlights the innately slanted nature of the distribution of information as well as its messengers. Rugg has also created hand-drawn works alongside wallpaper installations, both of which toy with authenticity and falsehood through subtle trompe l’oeil.