Taken together, the three memories in my poem ‘Signs‘ denote my progression towards finding a voice as a deaf writer. The intense pain and sensory overload that I experienced on that early spring day was caused by meningitis. The doctor gave me a large dose of antibiotics to clear the infection on the lining of my brain, but this damaged the hearing in my left ear and half in my right. This was why I couldn’t hear my father’s words clearly.

I was obsessed with books such as Strawberry Shortcake when I fell ill. As I’d learned to speak by then, and I clearly loved words, my parents decided to send me to the local primary school, which meant that I was raised as an oral-deaf person (that is, a deaf person who uses her voice to communicate, rather than her hands to sign). I had speech therapy from a teacher for the deaf once a week, and now people rarely notice I’m deaf unless they see my hearing aid, or I tell them. This raises another set of problems: I pass so well as a hearing person (largely by dint of lipreading and sheer hard work), that people fail to accommodate me by speaking more clearly, or forget to include me in conversations. Consequently, it’s easier for me to read than to listen to and interact with people. Reading was a solace when I became sick, and has remained so ever since.

My deafness aside, the aura of those letters living beneath the dresser suggests that words were always going to be significant for me. Shuffling them into words presaged my decision to become a writer when I reached my late teens. I poured the stress, frustration and isolation that came with deafness into journals. Later, when I developed my literary ability, I crafted my emotion into novels, stories, poems and essays.

As well as guiding me towards writing, deafness also profoundly influenced my literary voice. The part of my hearing that survived is in the upper registers, so I hear women’s voices more clearly than men’s. This means there is less chance of confusion and mishearing when I listen to women, and less chance of being mocked if I miss something.

When I learned about feminism at university, my affinity with women’s voices exploded into a passion. I particularly identified with their historical efforts to find a voice, and to have that voice published in a world that was hostile to them. As Virginia Woolf, with her ever-elegant turn of phrase, wrote in A Room of One’s Own: ‘One can measure the opposition that was in the air to a woman writing when one finds that even a woman with a great turn for writing has brought herself to believe that to write a book was to be ridiculous’ (68).

Deaf people, too, have had a long and contested relationship with writing and speaking and, like women or other minorities, they have fought to be heard. The suppression of their voices is due to Western theology and philosophy’s association of logos, or reason, with the voice and the spirit with breath (Davidson 91). This association began with the belief that speech was of divine origin – that is, given by god. The Christian church decreed that if deaf people could not hear the word of their god, then it would be blasphemy to teach them. Gradually, through the efforts of monks such as Fray Pedro Ponce de Leon (1529–84) who taught the deaf children of aristocratic Spanish families anxious to keep their wealth by passing it on through these children, it was discovered that deaf people could be taught to speak (Markides 6). Two centuries afterwards, teachers such as the Abbé de l’Epée (1712–89) in France showed that deaf people could communicate freely and easily using sign language. His successor, Abbé Siccard, taught Laurent Clerc, who together with Thomas Gallaudet established what would become the first university for the deaf in America, Gallaudet University.

Despite these endeavours, the oral-education method of teaching deaf people to speak gained traction near the end of the nineteenth century. It was influenced by prevailing ideas on eugenics and prominent spokespeople such as Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone. Bell, whose deaf wife communicated through lipreading, believed that deaf people should marry hearing people to avoid ‘a formation of a deaf variety of the human race’ (4). Endorsement of the oral method was cemented at the International Congress for the Deaf held in Milan in 1880, where it was resolved that deaf children worldwide should be taught by the oral method and that sign language was to be discouraged.

The denigration and suppression of sign language, which has lessened only in the last 40 years or so, has placed considerable pressure upon deaf people to conform to the dominant hearing culture. This means pretending to hear when one cannot, speaking instead of signing and never disclosing that one has a hearing loss. However, for those who are born deaf, it is much easier to learn to sign than to use lipreading and speech, both of which require huge amounts of concentration and energy.

In tandem with this impetus, deaf people have been encouraged to write as well as sign so as to communicate with hearing people, even when writing has not come easily to them. Jennifer Esmail, in Reading Victorian Deafness, notes that ‘when deaf Victorians were writing in English, they were almost always writing in their second language. They were typically signers first and writers second, yet they were forced to use written English to represent themselves textually’ (201). Even at Gallaudet University a century later, as deaf rhetorician Brenda Jo Brueggemann writes in her 1999 text Lend Me Your Ears, students were expected to become skilled in both American Sign Language (ASL) and Standard Written English, even though ‘ASL and English differ radically – syntactically, conceptually, modally – in almost every way’ (50¬–51) and ASL has no written component. Despite these tensions, deaf writers have mobilised both written English and sign language to express themselves.

Deaf Poets

‘The deaf poet is no oxymoron,’ John Lee Clarke opens his essay ‘Melodies Unheard,’ ‘but one would think so, given the popular understanding that poetry has sound and voice at its heart … As a result, deaf poets are often objects of amazement or dismissal’ (165). This was particularly pronounced in the nineteenth century, when written poetry was linked with orality, often in terms of formal features such as rhythm and rhyme (Esmail, ‘Perchance’, 509). Undaunted, deaf poets of this era frequently created poetry. The network of periodicals created by and for deaf people included monthly poetry columns, while important events in the deaf community ‘were commemorated with poems written and signed by pupils’ (Esmail, ‘Perchance’, 510).

Hearing audiences, however, emphasised the seeming incompatibility of the deaf poet’s craft, and they marvelled that deaf people were able to produce poetry at all. In the first volume of the American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb (1848) is a poem, ‘The Mute’s Lament’ written by John Carlin. Preceding this is an article, ‘The Poetry of the Deaf and Dumb’, written by the editor who expresses wonder that the poet, deaf since birth, had produced a poem:

How shall he who has not now, and who never has had the sense of hearing; who is totally without what the musicians call an ‘ear’, succeed in preserving all the niceties of accent, measure and rhythm? We should almost as soon expect a man born blind to become a landscape painter, as one born deaf to produce poetry of even tolerable merit. (14)

The editor’s surprise notwithstanding, many deaf poets did reproduce rhyme and sound in their work. They also wrote poems that included birdsong, music, wind, the human voice and musical instruments, and invested these sounds with tone (Esmail, ‘Perchance’, 522). In Carlin’s poem ‘The Mute’s Lament’, for example, streams murmur ‘gaily’, the linnet’s song is ‘dulcet’ and the organ’s harmony is ‘sweet.’ These adjectives indicate that ‘deaf poets who do not have access to a sensory experience of sound … they have access to a textual experience of sound derived from conventional phrases’ (Esmail, ‘Perchance’, 524). Sound is conveyed to these poets not through their ears, but their eyes.

This seeming contradiction is borne out through the figure of the mute poet, Carlin’s narrator, who lists the sounds of birds and lutes, but brackets them with the refrain ‘I hear them not’. He also laments ‘My tongue is mute, and closed ear heedeth not’. Even as he proclaims he cannot hear, the very act of narrating is a speech act. Carlin’s narrator destabilises the concept that poetry must be spoken and heard, for here is a deaf person speaking and creating sound through the silent text. Esmail’s skilful analysis of this poem and its implications demonstrates that ‘the ear is only the imagined, but not the necessary, home of poetic ability’ (‘Perchance’, 576).

This distinction has been grounded further in the emergence of signing poets. These are poets who ‘do not write. After all, writing is not native to Deaf culture as is signing. They make poetry out of handfuls of air, their lexicon cinematic and giving rise to a new poetics’ (Clarke 169). Visible, or signed, poetry, gathered momentum in the 1980s when Ella Mae Letz and Clayton Valli, unbeknownst to one another, began to produce signed interpretations of poetry in America. At the same time, a 1984 workshop between Allen Ginsburg and deaf poet Robert Panara of the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID) in Rochester, New York, sparked a new generation of signing poets. In conversation with Ginsberg, Panara observed that ‘For deaf people, signing poetry is like “painting pictures in the air”’, to which Ginsberg replied, ‘The ambition of a good poet is to write something that is visually clear and bright … It’s fortunate that modern poetry is the closest verbal formulation to what might be useful for deaf people’ (Cohn 266). Cohn writes that this exchange ‘has historical implications for the Deaf because it validates the formation of a sign language poetics that in itself is not isolated but is part of a developing international poetic style based upon an awareness of the importance of the image’ (266). While Cohn’s desire for deaf poetry to be validated by a hearing poet is problematic, the exchange fortuitously gave rise to a series of signed performances at NTID under the auspice of The Bird’s Brain Society. Discussions about these performances revealed ‘a previously undocumented level of metalinguistic, and specifically poetic, awareness of sign language as an art form by the Deaf’ and included observations such as: ‘A deaf poet’s strength is in the visual expression of the poem’, ‘Sign language does not require English’ and ‘I’d want to see the deaf audience cry. I’ve never seen that happen’ (Cohn 268–269). That Peter Cook, who conceived the title after a poem of Ginsberg’s, is still performing is testimony to the strength of and interest in signed poetry.

Bauman, Nelson and Rose, in their text on American Sign Language literature, Signing the Body Poetic, articulate how signed literature differs from traditional prose and poetry:

Poetry often conjures images of lines not quite reaching the right margin and the musical incantations of the speaking voice, whereas prose evokes images of justified margins, indented paragraphs, chapters, and books held by silently engrossed readers. But in sign literature, the same hands, face, and whole body used for everyday eating, sneezing, and lifting are transformed into the kinetic shape and skin of the poem. Here, reading becomes viewing, books become videos, and paper becomes a performing body. In a most literal sense, this is a form of ‘writing-the-body’. (2)

Examples of such bodily writing and reading can be found on the website of the library of The Rochester Institute for Technology, with which NTID is now affiliated. A subject guide for ‘Sign Language Literature and Poetry’ includes a list of YouTube and online videos of signing poets, such as ‘The Stars are the Map I Unfurl’, a British Sign Language poem by Gary Quinn which celebrates the first deaf round-the-world solo yachtsman, Gerry Hughes. The piece, performed by Quinn and interspersed with images of Hughes on his yacht, is accompanied by written versions of the poem in English and Shetlandic. Kyra Pollitt, a British Sign Language interpreter, poetry researcher and artist, collaborated with Christine de Luca to create the literary interpretations of Quinn’s poem. David Bell provided kinetic titling, providing another layer of translation, but also making the film accessible to an audience that does not know sign language (‘Signed Up’).

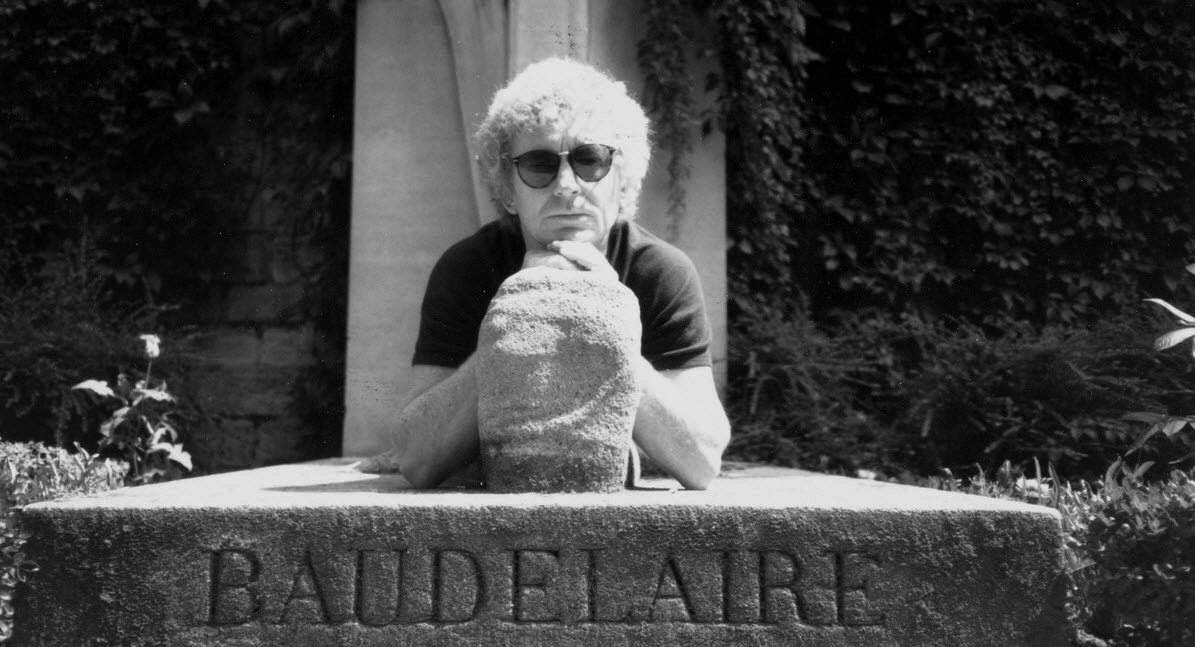

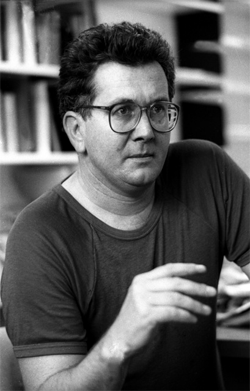

Writer in residence at ANU with Robert Adamson and Nigel Roberts, 1987 | Image © Juno Gemes

Writer in residence at ANU with Robert Adamson and Nigel Roberts, 1987 | Image © Juno Gemes

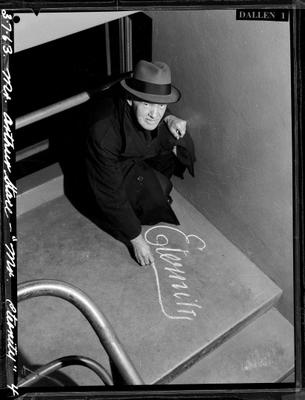

Writing written over writing

Writing written over writing