Why are you here?

in response they say Softness

I still can’t tell if I find that answer satisfactory

In the middle of the night

in the middle of a shared pandemic

I lay on my back not falling to pieces

in the middle of the clay-pans

in the middle of three-ways

I am falling into peace

concealing my eyes in the middle of rapture

inhaling their Requiem of silence in D Minor

I frolic in the middle of denial

if it pleases the jury of midnight recovery

and all that glitters is not quite sold

I crave the cravings of my Jewish lover

her middle-finger figure-skating around

the outskirt of my arching sovereign mouth

over there, where – against the rocks of

somebody else’s songlines

she and her gather well-heeled in the middle of

an open fire-engine-red chaise longue

pressing if we must

into scalloped watercolours

dividing rehearsals all over again,

and again, and again

in the middle of a raftless desert-sea

I catch a fallen star from the ankle of a

petulant Milky Way

placing it firmly inside my lover’s middle pocket

in the middle of nowhere

yet someone else’s somewhere

remunerating each other’s unravelling limbs

in dialogue for spare body parts

suddenly, in the middle of an unordinary stanza

I choose to release her Hebrew stare

in the middle of a shared odyssey

halfway through mid-sentence

syphoning the foam

between Scylla and Charybdis

ego aside

my therapist survives

Whilst I, the sometime poet

by the bye return to my lovers’

unpublished womb

I’m honoured to announce that Rory Green will be taking up the helm of Games Literature Editor for Cordite Poetry Review, and to finally get back to using the online space and capabilities more consistently than we have the past decade.

Rory Green is a writer, editor and digital media artist living and working on unceded Gadigal land. Their interactive digital poetry has been presented at festivals including BLEED and Cementa, as well as published in Cordite Poetry Review, The Lifted Brow, Running Dog and Taper among others. They previously edited Voiceworks Online, a publication for experimental digital writing by young Australian writers, and facilitated Express Media’s online learning program Toolkits: Digital Storytelling. Their debut chapbook the attentions was published in 2022 through Slow Loris. Rory’s current ongoing project is to write a poem for every Pokemon via the email newsletter Otherwise Pokedex.

For Aunty Kerry Reed-Gilbert, 24 October 1956 to 13 July 2019.

I think I might see you when I walk out this morning along the street we used to share. Winter is bleak in Kambera. Icy winds off the mountains, sleeting rains, low-hanging sun-fired fogs bring birds down into the hollow of the suburbs.

They come in droves. Rainbow lorikeets, corellas, king parrots, crimson rosellas, galahs, gang-gangs, and sulphur-crested kuracca – your totem.

It was not meant to be. I turn the corner and the wind hits me cold and sharp in the face like the reality. You are not here in this house with jasmine clad front fence, lilies by the door. A place of grandchildren and Aunties, where us mob gathered to write. Talk our Blak lives. Dream our rainbow visions.

Early on the morning of your passing a thick cloud of kuracca swept in flying low above your old house, calling loud, taking your spirit home. Releasing all that was unsung of you across the open sky.

For Aunty Kerry Reed-Gilbert, 24 October 1956 to 13 July 2019.

In this valley,

generations of glistening gums reach skyward

Roots reaching deep,

Holding earth

I imagine lying here

Warmed by a fire

Billy tea, some damper

My dog and me

Whip birds call and respond

Flashes of sound,

Hisses and hums

Magpies

Shifting light,

Shadow dust, where dry cracked earth lay broken

Creeks now overflow

Food and medicines everywhere

Purple lily, fringe lily,

Casesia Calliantha, Thysanthotus Tuberous,

Daraban, Munong, Yam Daisies, Microcseris Lanceolata,

Mummadya, Cherry Ballarat, Exocarpos Cupressiformis

Cauliflower bush, Cassina Longifolia

I am searching for words, confused at the order, the correct naming

Elusive, beyond my reach, clumsy in my mouth;

Wrapping myself around the silver flesh of a tree

Eyes closed,

I float for just a moment

Suspended…. Kissed by the breeze

Dissolving, becoming, returning

As country sings

In partnership with FNAWN, we are proud to publish the winning poems from the 2022 KRG Poets Award. The award honours the life and creative work of Aunty Kerry Reed-Gilbert.

Said judges Marissa McDowell and Ellen van Neerven of the winning poems, they are ‘beautifully crafted, drawing breath and captured memories’.

The winning poem by Samia Goudie is Call me by true names.

The highly commended poem by Jeanine Leane is Unsung.

For OPEN, we’re interested in doublings, triplicates etcetera, and/or play and suggestion; we’d love to read poems that open meanings, spaces, possibilities and forms, that take open as their verb and move with it, into and beyond synonyms … poems that bud, unfold, extend, splay, drape, burst; poems that take up space and poems as lacunae: absence made palpable and present.

This issue was first conceived in mid-October 2021, when states were opening up in easing lockdowns and restrictions – but for or to whom is the world open; what kinds of lives are included and visible in these discourses and their assumptions, and what kind of view or vantage point can the Australian colony take on being open – on stolen lands, with stopped boats and borders, kids in custody or indefinite detention, detained off-shore or in Melbourne’s Park Hotel nine years and counting?

What does open look like to essential workers, frontline health workers, casualised workers, those in aged care or most vulnerable to sickness and health crises, and to social inequities more broadly? We’re interested in poems as portals, in the sense Arundhati Roy once described.

Fundamentally, we’re keen on crafted poems and crafty poems: writing conscious of its own making, unmaking, and making it new, of its contexts and antecedents, but we are obviously – and axiomatically – open to all kinds of apertures.

This podcast sheds some insight on how Cordite Poetry Review (and Cordite Books) works.

Submission to Cordite 106: OPEN closes 11.59pm Melbourne time Sunday, 3 July 2022.

Please note:

White Clouds, Blue Rain by Oliver Driscoll

White Clouds, Blue Rain by Oliver Driscoll

Recent Work Press, 2021

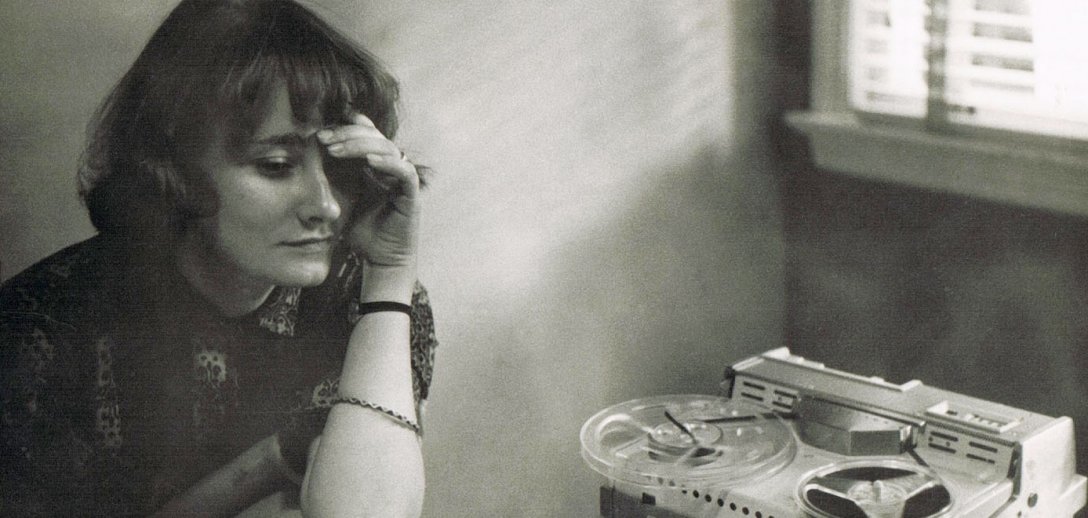

White Clouds, Blue Rain (2021) is Oliver Driscoll’s second poetry collection, appearing a short year after his 2020 I Don’t Know How that Happened. Like his earlier work, it is concerned with the everyday: small moments of domesticity and care; conversations both mundane and profound; fleeting interactions with, but more often, observations of, an outside world whose parameters are undefined, but which nonetheless feel tightly bound, contained. To say that this is a result of the pandemic, which has certainly imbued domesticity and its imaginary with a gravitas denied to it when it was considered womanly, would be incorrect insofar as Driscoll has always had an eye for the ordinary, has always been pulled by the intimate, the close.

If the collection has been affected by the pandemic, it might be seen in a slight shift in focus between I Don’t Know How that Happened and White Clouds, Blue Rain – while both dwell on interactions between people, the former is briefer in this, whereas White Clouds lingers and returns. Relationships, as much as the quiet maintenance of home, are central to the collection in a way that cannot be easily disentangled from the isolation and distance imposed by Covid-19: relationships to kin, to neighbours, friends, a lover, as well as to writers and artists and their work; existing relationships, experienced either in memory or within a proximal radius, or one-sided relationships are entirely maintained in a contactless abstract. We meet few strangers in White Clouds, though we watch them.

The collection is structured in a series of triptychs: a poem, a piece of extended prose, a black and white photograph, all untitled. These images, especially, add to the collection’s sense of disconnected melancholia. Mostly, they are photographs of a domestic made eerie through greyscale: the acute corner of a roof against sky, the cluttered corner of a room, windows flooding light into an over-saturated corner. Corners, actually, appear and reappear in these images, betraying a preference, perhaps, for the clean lines of the geometric. Indeed, the triptych structure is rigidly maintained throughout, glitching only in the last section when paragraphs break into the poetry, temporarily jostling the stanzas aside. The effect is inconclusive; something is undone but nothing is loosened. The slip is not jarring because the poems, like the sections of prose, are direct, unassuming and restrained. At their best, they are spare – almost thin – yet dexterous and surprising, as in this stanza in the collection’s last poem:

By now we know that not only do

eggs and bottles not have to look like

eggs and bottles

but

they don’t need to be painted at

all

These poems are not the main event and do not pretend to be. They are the deep breaths before launching into speech.

Perhaps ‘before launching into a monologue’ is more apt, a monologue in which domestic mundanity is given sumptuous expression. Everywhere there is the enumeration of things tidied, cleared, fixed, put to order, of books read, conversations had, thoughts idly pondered. It is deeply comforting to read of Driscoll cutting back ivy on a fence, pulling rubbish out from the back of his property, feeding his neighbour’s cat or taking out the compost. To encounter such simple acts of care over and over is nurturing in itself. Likewise, his relation of numerous conversations feels like having the radio on, a constant, comforting buzz. The conversations themselves vary in theme and emotional resonance and, at times, can feel a little contrived – a little too well turned and clever. Whether or not they are faithful representations of what was said is often beside the point: when they work, they are elegant and profound, as when he recounts his mother’s reaction to her grandchild breaking one of her ceramic pots: ‘Some pots, she wrote, have a lifefulness, but most do not.’ Even when these reports feel as though the borders of truth have been bent, the bending can be dismissed for the grace Driscoll offers us. For example, when Driscoll describes a conversation with friends, he relates a young woman he hadn’t previously met saying that ‘When it’s raining heavily or just cold and damp, she has the sensation that memory is located on the other side of her apartment walls.’ I cannot bring myself to care whether or not this was actually said, it is too moving an idea to not be repeated.

Driscoll’s interest in the small and near, taken with his direct, sparse style, engenders a curiously untextured world, albeit not a flat one. It’s rather that his sentences are so unadorned and clear that they necessarily draw straight lines and distinct shapes. They have the effect of an Edward Hopper painting: simple, restrained, still, melancholic in a diffuse, unspecific way. Dreams, memories and observations are recounted in the same tone, and relationships are conveyed through conversations recounted at a consistent anthropological remove. Everything is drawn along the same perspectival plane, everything equally close while being observed from the same distance. Depth accrues over the reading, as a mood or general vibe. There is no meaning, per se, but it feels like it.

In my favourite prose section, for example, Driscoll deftly interweaves anecdotes about camping with his father with fragments about boys lost in a New York sewer, a friend pulled from a river by his father, catching yabbies to eat, going to call his mother and not calling his mother, a broken piano key and others, each turn building a gentle tension that reaches its climax with Driscoll deep in a cave, inches away from a hole whose bottom is far too deep. The section is exemplary of how the collection as a whole is disconnected from time, moving across years in graceful loops, dipping into dreams, ruminations on books or art, conversations and snippets of life, unsituated yet accruing. The digressions are many and at their best, they are tangible: grounded in a history that is intimate and lived.

Artwork by Bella Li, from ‘New Gods‘ (Liminal, 2019)

Liminal and Cordite Poetry Review are seeking poems by Asian Australian writers.

Send us your single best poem!

Poems can be written texts (including micro-fiction); visual, audio or video work; or a combination of forms.

In your submission, please include a positionality statement, confirming you are a citizen of, or residing in, so-called Australia, and identify as Asian Australian. We recognise the emotional toll in ‘proving’ one’s identity, but for this project, it is a necessity. We’re trying to avoid a Michael Derrick Hudson incident.

Submissions will not be read anonymously, and will be guest edited by Bella Li.

This issue will publish in concert with critical essays commissioned for Liminal Review of Books that respond to Asian Australian writers and artists that have been published in Cordite Poetry Review over the past 25 years.

Submission to Cordite 107: LIMINAL closes 11.59pm Melbourne time 24 April 2022.

Please note:

Cities by Petra White

Cities by Petra White

Vagabond Press, 2021

Petra White’s poetry has been highly and widely praised, celebrated for its seriousness, its engagement with poets like Petrarch, Dante, Coleridge and Donne, its ability to ‘recall’ these famous European names and their famous poems. She is presented as a serious poet, and has managed to get her ‘kind of Collected-poems-so-far’ (Duwell) onto the VCE Literature text list. I wonder what this says about poetry in Australia. Her poems are so good on one metric (studious, ‘clever’, instructive), and so bad, downright naughty, on another (stylistic and/or political ‘radicalness’).

Even before you open it, Cities has an aura. The cover has barely any textual support, an identical Anthropomorphic Deity (Julian Gordon Mitchell, oil on canvas, 2015) looms over the front and back and no blurb. Despite this openness, there is enough paratextual material to push us toward a particular reading. From the Vagabond website: ‘Cities makes playful and lyrical incursions into myth to explore the nature of grief for a mother while becoming a mother, and the difficulties of love … [And] “journal” poems [partially about the] strangeness of prolonged lockdowns’ for life in global cities. Quite a heavy load.

White’s poems are sombre little lights in darkness. I read them closely, slower than I normally would. I’m even compelled to speak the words aloud, a little treat. They feel old and demanding. (What are they demanding?) It is nice to slow down, something I’m not very good at, especially nowadays. Poetry ‘helps’. I’m wary of the therapeutic in art, but White’s decision to publish Cities suggests her belief in poetry’s usefulness for a troubled soul. The poet brings wisdom through elegy and eulogy in the first two of four sections:

The lights of the living are not lost on the bygone, they drink them up like baby birds with sinewy necks. Drink the light that swims through Hades, and are warm. Oh my dead, I will be your queen.

But White is cagey in her extension of the self in mourning. To study her grief, she turns to the mythic figures of Demeter and Demeter’s daughter, Persephone, queen of the underworld. These two deities form a transcendental image of mourning, and point to immense feelings: ‘one goddess / in the sunlight of another’. Potent lines like this fill out much of the long poem ‘Persephone at 40’. Aside from one cheeky moment where Persephone takes pleasure in seeing another (Eurydice) suffer her own fate of eternal life in the underworld, the poem is austere, turning to classic themes with little innovation, flaws or tics – the seasons: ‘Ah, Winter, season of my mother …’ and solitude: ‘My mother cannot guide me / my husband ignores me’.

By contrast to the deities, White looks at human life and motherhood as being defined by its finitude, and made meaningful by it. While Persephone sooks: ‘I could love her more if I knew she would die’, humans ‘pray and cry and do all that’. Persephone’s mother is philosophical:

Tell me what a mother is, tell me for I do not know. Is it a ghost, a wound? A nothingness, an echo, as when she sang into the cave to hear her own voice--

‘Demeter’s Song’ is a dark nursery rhyme for adults, a quality echoed in ‘Mother On Men’, which begins with (and repeats) the annoying phrase: ‘Mother what is a man?’. ‘Demeter’s Song’ has only four more short lines which mirror the first four. We might think (concretely) of the bottom quatrain as the underworld, Demeter calling down:

for a huge-headed mother a sweetness hard to bear. Sing to me daughter, upwards through the darkness’.

This poem, like most of the very consistent Cities, trades in familiarity: ‘darkness’, ‘sweetness’, ‘mother[s]’, ‘ghost[s]’, and the extended universe of Greek myth. It has an aphoristic quality that holds the promise of profundity, wet-eyed, important.

We are a long way from cities, or, cities as we conventionally think of them are a distant backdrop. The city is figured as a mass of atomised grievers, who share stories, and together build the places we know as London, Berlin, etc. The poems, if they take place in the city, capture life inside it through a fisheye lens, everything around the speaker blurs and moulds to the centre, the speaker’s bug-eyes pleading, as in the obscenity of lines like ‘Sing to me daughter’. This language can never be broached in an actual city. To grieve, White shows, we have to turn to Poetry, away from the city. We have to write ‘To My Mother’s Ghost’. White affirms the power of art, but the actual writing to the ghost, ‘the numinous one’, is stylised and troped. It makes little use of the actual potential of poetry: ‘If you were down there / in the underworld I would look for you.’

There is so little flashiness, to a degree that feels sort of bold. Duwell lauded White’s ‘nothing superficial’ but I crave that – one quick thrill was the appearance of a chicken shop in a poem’s title, but you don’t feel the particular ambience of a chicken shop in ‘Chicken Shop’ so much as the platonic ideal of a place where you might accidentally leave your daughter behind, as the poem goes on to imagine, which is sort of funny actually, that ‘analytical’ mode of writing about a chicken shop. White is not eager to charm or flatter her audience. The difficulty produced by these unplaced, undetailed poems (in part I and II) suggests an attempted universalism.

Maybe I need to peel back. White’s caginess and ‘analytical’ mode must be partly due to the project’s personal nature: the grieving of her mother. Myth is a kind of self-protection; I feel inoculated from the grieving. So I’m left with the sense these poems voiced by ‘universal’ figures will never cut through to deep feelings. That is not their aim; their aim is to cloak grief in order to memorialise it. Sometimes White’s lines cling to cliché as a result, renouncing poetry’s duty toward inventiveness: ‘a mortal knows – / what you love you must lose. / But accept it? / Impossible as breath / under water.’ Cliché is not necessarily a bad thing. It can be good like a good pop song is good (a matter of opinion?). It can signal a timeless way of looking and acting (‘What I did, a mother would do’), and from this position, White makes lovely lines ‘… if I could hold / like flesh the empty air’. But is it bad to say: ‘What I did, a mother would do’, to speak timelessly, as a / the mother? This is an example of the conservatism of Cities: White is not signalling the fact that she is doing a critique of her own language while writing, and she writes to make sense by utilising familiar ideas and easy to understand ways of understanding those ideas.

I love White’s rejection of ‘rupturing language’ in theory, but find it alienating in practice. Occasional bursts of realism don’t help much. Anecdotes like ‘when she was a seventeen-year-old pantomime actor / and bowed to dark applauding space’ feel more like a stock photo than something living and breathing. Sam Langer, reviewing White’s second collection for Arena, referred to it as ‘honeyed’, both preserving technique and aesthetic gloss. Langer suggested the poems in The Simplified World demand ‘decod[ing]’. In Cities, any ‘private messages’ are to remain private, the poems less puzzles than prayer. They wear their meaning on their sleeves:

And at home I listen to the baby’s planetary breathing, each breath a second of her life and mine the impossible love that loves her every second.

Petra White stands out in that a lot of Australian poetry is so tongue-in-cheek when looking at canonical themes. From John Forbes to Evelyn Araluen, many Australian poets share a desire to defile the sacred myths of the west, an impulse White doesn’t have. Her poems are porcelain treats. These treats are part of a city, but don’t attempt to reproduce the feeling or image of a city. Why is White so far from the street, the workplace, the agora? In Cities, the real cliché is the hustle and bustle of avant garde art, from which the author turns. Nothing breaks: ‘For My Daughter Ten Weeks Old’ conserves the life of the baby, ‘Slumber in my wolfing gaze …’ She presents maternal relationships as if they were timeless:

Dark spirits of motherhood come with gifts of frailty, they say I will suffer, and fail, and you will not forgive me —

TAKE CARE by Eunice Andrada

TAKE CARE by Eunice Andrada

Giramondo Publishing, 2021

‘The actor is a heart athlete,’ Antonin Artaud wrote in 1958. He was writing about theatre, but I wonder if the same could be said of the poet. ‘To arrive at the emotions through their powers instead of regarding them as pure extraction, confers a mastery on an actor equal to a true healer’s. A crude empiricist, a practitioner guided by vague instinct. To use emotions the same way a boxer uses muscles. To know there is a physical outlet for the soul. (93 – 95).

Eunice Andrada’s second collection, TAKE CARE, demands its readers to become heart athletes too, as we proceed through poems about rape culture perpetuated by men in positions of power against Filipino women, care workers and poets alike. The poet is both heart athlete and fighter in a ring, like Oberyn Martell (Pedro Pascal) versus The Mountain (Hafbór Júlíus Björnsson) in the fourth season of Game of Thrones. The season ends with a trial by combat, where Oberyn demands that the Mountain confess to raping and murdering his sister and daughters. Oberyn almost wins the fight – until he makes the mistake of coming too close to an enemy who overpowers him with strength and size. The Mountain digs his thumbs into Oberyn’s eyes, admitting to the crimes. Dying in the Mountain’s grip, Martell’s demands meet an obscene satisfaction.

Sexual racism functions in a similar manner: announcing itself, narrating itself, calling itself ‘literature’, welcoming protection, parading its self-pitying subjectivity in front of a paying audience. It’s hard to imagine that catharsis is what this collection seeks.

Andrada’s opening dedication reads, ‘For kapwa, by blood and experience’. Kapwa is often translated into ‘neighbour’. In my own lived experience of the language, it feels more generous to translate kapwa into ‘kindred’. To be among kindred is to be among one’s own. The poetry here is about how class difference is experienced through a raced, gendered subjectivity from the Global South. The collection explores what it is to exist within the semiotic clusterfuck of what’s possible and impossible as a young Filipino working-class woman.

‘The Chismis1 on Warhol’ opens with a quote from a poem by Alfred A. Yuson, an award-winning Filipino poet whose career has included prestigious placements in highly regarded Philippine and American universities. The poem is titled ‘Andy Warhol speaks to his two Filipino maids’. Andrada’s poem is about this poem. She quotes Yuson’s lines: ‘Art is the letters you send home about the man you serve.’ Andrada writes:

Wonder what he eats at home, What Nena and Aurora must prepare For his guests. While he’s with guests, who cares For his mother? And while he slurps Oysters with Imelda? Didn’t they tell him to be careful of Imelda? Who cares for their children while they’re gone?

Where We Are is about place (where), people (we) and the present tense of existence (are). The place could be two, Scotland and Australia, but really it’s one: wherever we find ourselves. The people could be poet, family and friends, poet and reader, or all of us on this drowning, burning earth. The present tense could be this moment, or a past so intensely remembered, or a future so powerfully imagined that past, present and future are simultaneously here.

Conditional responses to the poems seem not only possible, but necessary. There’s much that slips in and out of light, and Flett’s poems have a zero-sum gaze: where there’s not light, there’s darkness. In ‘Wherever This Is It’s Where We Are’, there is ‘thedarkthatsurroundsus’ and ‘the labyrinth of dark streets’ and ‘the crow’s black heart’. There are the hunting shadows of Tenebrae, the service of falling darkness. And the fox’s ‘wet black pavements’ and ‘red-black fur’ and ‘black-red eyes’ in ‘Semiosphere’ (shades of Terrance Hayes’s ‘black-eyed animal’.) The fox slinks in and out of darkness, in and out of sight and comprehension. Darkness isn’t always threatening – it’s just that we can’t understand inside it.

We read some of these poems as stories, because inventing narrative lines – that may not be there – makes sense. ‘Seen Through’ is six window views, from living room to B&B to Hilux to tent to pub and home. We read the ‘to’s into this, they’re not written in, making it a traveller’s tale, a road trip up the ‘Oodnadatta stretch’ and on to Uluru and back. ‘Still Life in Library with Keys’ might seem like a painting, as in Kelman’s version of Cézanne’s ‘les joueurs’, but it’s alive – it’s still life, not a picture of it. It’s the story of a poem being written, or unlocked, or emerging, among the millions of words shelved in the library. Brand-new text born out of old but also out of the library’s pigeons, passers-by, line dancers, self-talkers, soup-eaters. ‘Nothing but noise’? Nah, we hear poetry.

Tomas Tranströmer haunts Irvine Welsh in ‘Liminoid’, a prose-poem yarn in Edinburgh Scots: ‘a tousie bunch’ of partygoers glimpsing a fox (that doggone beast again!) out of the corner of an eye. There you go: a second Scottish prose writer, but not a poet in sight, because there’s no glimpse of contemporary Scottish poetry here. Twenty-five years ago, Flett’s work moved in tight formation with Tom Leonard, Margaret Hamilton and Ian Hamilton Finlay. Now, having flown half way round the world, she’s in an orbit with Ken Bolton, John Forbes, Jill Jones, Eileen Myles.

In ‘There Is a Bigger Telling That Moves Around the World’, words make the world go round: language is ‘the ultimate thump thump’. ‘Telling’ is counting, what a teller does after elections. The vote here was a choice between ‘a song of YES’ and the ‘cold NO’ which won. But there’s hope for YES next time because ‘we have all the words’. Those Australians at their barbecues talk so much that words form a ‘tumulus’, ‘mounded over us’. The great heaps of ancient civilisations are tells. Is that what the builders are shouting about? When we read ‘something/that might have been done was not done’, we catch the echo of Scotland’s many hill fort duns – Dunbar, Dundee Law, Dùn Èideann. The story goes round: we could have built a castle, but cold NO won, and we didn’t. Still, the builders are busy, they’re opening the ground. Maybe they’re digging to Australia. Or maybe I’m digging up far-fetched meanings. And? You want to make something of it? Go ahead: build.

Here we are with a poet who knits intricate patterns of sound and image, line to line, poem to poem; a poet who pays attention to W=h=e=r=e=W=e=A=r=e and makes it heartbreaking, breathtaking, beautiful.

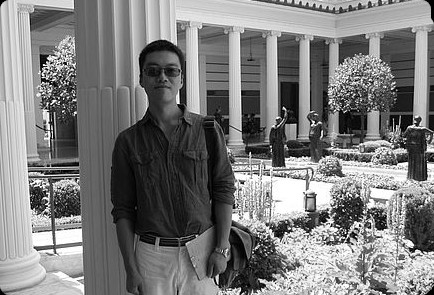

In this work of a mature artist, Kim Cheng Boey’s characteristic style – literary, allusive, memoirist, with a flâneur’s sensibility – is on full display. The book’s triptych staging – ‘Little India Dreaming’, ‘The Middle Distance’ and ‘Sydney Dreaming’ – unfolds as a bildungsroman, in which place and time generate itineraries that signify more than the pleasures and travails of travel or the sociopolitical content of the émigré shuttling along the spectrum of departures, arrivals, exile, immigration, and in-between states.

The three groupings sound distinctive emotional notes to encompass imaginaries that approximate Asia (Singapore and its neighbours), Europe and the Americas, and the Pacific Cosmopolitan. The last is situated specifically in Sydney, where the poet-subject is reborn with his first child, conceived in Singapore; where Nature and Others, recognisably self-constructed, conclude the narrative of Becoming.

In the first part of the book, the presences of father and mother are also the shadows of their absences. Memories of idyllic moments are barely grasped before lamentations of loss follow, such as in the introductory poem, in which the speaker ‘see[s] … [his] face multiplied, split between lives and places … All gone now. Diaspora. Dispersed. Disappeared’. The romantic lyricism that vivifies images of lush tropical vegetation in ‘The Botanical Garden Suite’ articulates the primary paradox in the experience of transience: what can be remembered if memory is of absence and disappearance? The poems are layered over indeterminate holes, not material histories, patterned as filigree rather than palimpsest.

This poetics of paradox, grounded in vivid imagery, follows the becoming of a ‘lost’ subject in ‘The Middle Distance’, which hinges Asia and Australia. These travel tales, unabashedly erudite, mix the past lamented in ‘Little India Dreaming’ with particulars from foreign lands: sacred sites, domestic scenes, and ordinary folk going about lives that ‘gleaned echoes of our true home, /and the translations that made us neither this nor that / but the people … in the home / that has found us’. Here, the eighteenth-century Romantic ideal of travelling in ‘antique’ lands is repurposed as an existentialist sensibility: I travel, therefore I am.

The final part of the book, ‘Sydney Dreaming’, offers a reversal of the absence, loss, death and paralysing transience present in ‘Little India Dreaming’. ‘Staying Alive’, the opening poem, with allegorical vivacity riffs off songs and figures in Western popular culture – such as the Bee Gees, cosmopolitan Australian émigrés who, like the poet, sing of returning home. Poems of settlement arrive in this new country, where labour wins bounty from an Edenic Nature, and the housed self, freed of the past, lives in the moment. This subject, holding to no religious or political ideology, shakes off the solipsism of the lone traveller in the Australian collective: ‘We are all from somewhere else, bits of Asia transplanted,/ grafted’.

The collection never loses sight of its rhythmic pace in the walking itineraries that thread origin, middle and end. ‘Sydney Dreaming’ is dominated by a first-person flâneur who emerges as Australian Asian, finding a filial self still haunted by the old Singapore. Boey’s itineraries of place and time in Sydney, however, transcend the themes of stasis underscored in Lee Tzu Pheng’s iconic Singapore poem ‘My Country and My People’, which declares: ‘[they] / are neither here nor there’. Walking out of a dream that constrains, the émigré Australian is ‘walking into this story, this dream, this map of longing drawn under the arriving stars’, which liberates and wins the future.

The more I think

The more I think about it the bigger it gets

The bigger I think about it the harder it gets

The harder I think about it the sharper it gets

The sharper I think about it the pointier it gets

The pointier I think about it the sorer it gets

The sorer I think about it the sicker it gets

The mirth I think about it the laughter it gets

The bisque I think about it the lobster it gets

The morgue I think about it the deader it gets

The years I think about it the older it gets

The sage I think about it the wiser it gets

The sound I think about it the louder it gets

The money I think about it the richer it gets

The think I get about it the better it gets

The gets I better about it the thinker it bets

The better I get about it the thinker it mores

The more it thinks about it the lesser I’m for

The less I know the more it gets

The less I am the more I know.

KIN explores how kinship, our understandings of who we are and where we come from, engages with dynamic senses of Country and belonging to Country. Country is storied, we are storied and kinship is nurtured and sustained by living and emergent stories about place and belonging. As Kaya Ortiz teaches us in ‘Naming ceremony’:

i am the long finger of country pricked with a needle to get to the blood where the stories live

The collection of stories within the issue recognise Country as a holder of knowledge, stories and memories about how we are interconnected. They trace how we have become kindred to Country and cultures. They account for diverse and complex understandings of kinship which collide, converge and unsettle.

Weaving together the stories within the collection, we listen deeply to a heartfelt yarn about navigating senses of place and belonging which patterns the mosaic of our global homelands. The yarn is unbound, artfully criss-crossing boundaries of homelands, generations and histories. It relocates the intimate, the domestic, and the ordinary from the periphery of cultural resonance to its centre. It asks the reader to reflect on fleeting moments of time, which hold living and beating histories of love, loss and yearning, and to feel their reverberations within our own chests. In ‘Mami Wata’, N’Gadie Roberts writes of such emotions:

dwelling in the crevices of my memory

The collection is imbued with a melancholic yearning to return to lost homelands, as well as a vivid agency of thought and expression to return in the words on the page. It impresses on us the significance of storytelling to give voice to desire, recognising and accounting for loss on the one hand, and hope and imagination on the other, to renew and rematriate our cultural life ways, and enliven self-determined futures.

The yarn about senses of place and belonging is grounded by First Nations understandings of kin. In the collection of First Nations writing within the issue, Country is kin. In ‘Yamaji Kin Songline’, Charmaine Papertalk Green reflects that:

I am kin to the old people now sand grains My barefoot lifting their spirits into my being

Country is living. In ‘Rivers’, Yeena Kirkbright writes of Country:

Three rivers run in my blood, where my mother takes me home

Country is sovereign, expressed in Samuel Wagan Watson’s powerful repetition of ‘I will not be moved’ … in ‘A Scorched Earth’.

The collection of stories within the issue move in time to an intimate rhythm of shared humanity. They teach us about an instinctive longing for home, family, kin and a sense of belonging in an ever-changing world. It has been a privilege and joy to guest edit KIN. I have been deeply moved by the daring vulnerability and honesty of the writers, and the creativity and experimentation within their writing practices. I would like to thank all of the writers who submitted their writing for the issue and generously shared their stories with Cordite Poetry Review.

door of air

eight of us under this ceiling, seven standing, one

supine then four sitting, three standing, one

supine, fingers interlocked over ribcage

seven people speak between dumplings

of quiet, not all of them entered with us

some left by the family before, they

filed out like a rosary of sorrow

room has two lungs, not like a heart

with its lop-sided cross, two lobes, one

curtain, one doorway of air at its left edge

nobody has ever, nor ever will

this division

because a world on one

side dreads the world on the other, though

One is the umbra of the other

this is a case of human

breaking at the threshold

of the door of air

Jorge Luis Borges Imagines China

A sandglass. A second. Touch of the finest skin.

Jade of joy. An itch. Secrets in books you have read

sans a page number sans a punctuation mark.

Chapter of the sun. Chapter of the moon. Chapter of the sea.

A pantomime script. A palindrome poem by an anonymous

author more beautiful than a chandelier, a rotating brocade.

A lady-in-waiting advising the emperor on Night of Devotion.

A chapter from Erya or a hexagram couplet from I Ching.

Wounded feet and iron shoes of Yu the Great. Waters rushing.

Shu Hai walks barefoot to measure the world, as prototype of K.

(Kafka knows he will never reach the two poles.)

Two gates to Hangu Pass, on the table sits

the first version of Tao Te Ching, ink still wet.

Affluent vacuity. Return of disappearance.

A tear from an ancient mermaid drips into a pearl.

Li Shangyin writes an untitled poem to some Daoist lady.

An Argentinian ant climbs up Mount Tai.

Sailors row in unison on Jianzhen’s boat.

Matteo Ricci draws in Zhaoqing’s Map of World’s Kingdoms.

The Great Wall of China seen from a spacecraft.

An ancient coin symbolises round sky square earth.

The sound of snow falling on the Grand Bell of Yongle.

The opulence and decadence of oriental Venice in South-of-Yangtze.

Archaeologists’ tweezers. Puppets’ pulling strings.

Unheard-of mysterious creatures in Classics of Mountains and Seas.

Silence of Terracotta Army. Furnace and sword of the Chinese alchemists.

Before a stele in Japan I read through the palms

of my hands the immortal inscriptions of the Middle Kingdom.

A bronze doorknob in Buenos Aires calls out to

another bronze doorknob in a Shikumen from Shanghai.

博尔赫斯对中国的想象

沙漏。秒。最细腻的皮肤的触觉。

玉如意。痒。你读过的书中

既无页码又无标点的秘籍。

太阳的章节。月亮的章节。海的章节。

哑剧的脚本。一首比枝形吊灯更美的

佚名作者的回文诗那循环的织锦。

宫女在奉献之夜对皇帝的规劝。

《尔雅》的一个章节或《易经》的一个对卦。

大禹的病足和铁鞋。滔滔江河。

徒步丈量世界的、作为K的原型的竖亥。

(卡夫卡知道,他永远到不了极地)。

函古关的两扇门,桌上摆着那

字迹未干的《道德经》的第一个版本。

空虚的富足。逝去的回归。

南海鲛人的一滴变成珍珠的眼泪。

李商隐写给某个女道士的无题诗。

爬上泰山的一只阿根廷蚂蚁。

鉴真号水手划船时整齐的动作。

一张利马窦在肇庆绘制的坤舆图。

宇宙飞船上看到的万里长城。

象征天圆地方的一枚古钱币。

雪落在永乐大钟上发出的声音。

江南那东方威尼斯的富庶与颓废。

考古学家的镊子。木偶的提线。

《山海经》里闻所未闻的奇异动物。

兵马俑的沉默。丹客的炉与剑。

我在日本的一块石碑前

用手掌阅读过的天朝的不朽铭文。

与布宜诺斯艾利斯的一个铜门环对应的

上海石库门上的另一个铜门环。

In the summer of 2015, Grzegorz Kwiatkowski and his friend Rafal Wojczal made a gruesome discovery. Walking through the forest outside what was once the Stutthof Concentration Camp, where Kwiatkowski’s grandfather had been interned during the Second World War, the two young men came upon several thousand old shoes. They were grimy and grey: single shoes, shoes in pairs, men’s, women’s, children’s shoes, all of them tattered, weather-beaten, many decades old. As Kwiatkowski and his friend cut their way through the undergrowth, they were to find many thousand more. These were the shoes that had been gathered en masse by the Germans during the war, taken from people murdered in Nazi concentration camps throughout Europe, and brought to Stutthof for a macabre recycling project, to be reworked into an array of practical leather goods.

Today there is a museum on a small part of the sprawling terrain of the Stutthof Concentration Camp. Grzegorz and his grandfather would go there when Grzegorz was a child, and his grandfather would weep. As part of the exhibit there is a great mound of shoes. But, as Grzegorz realised after his discovery in the forest, the mound of shoes exhibited in the museum is just a token. It is not indicative of the ‘mountains of shoes, bigger than houses’ that Sarah Hannah Matuson Rigler, who had been interned in Stutthof as a teenager, reported in 2010. ‘Mountains. I’m talking about as tall as buildings.’ She said there had been notes in many of the shoes – as they faced death, people scribbled last messages, hoping they would not be forgotten.

The many thousands of shoes Kwiatkowski and his friend found in the forest had been dumped and buried in the 1960s by a Polish government that felt it was better not to dwell on the painful and controversial years of Nazi occupation. A manageable number of shoes had been selected for the Stutthof exhibit; the rest were thrown away.

For Kwiatkowski, these actions and actions like them are symbolic of society’s preference for silence in the face of history’s terrors. In the poems translated here, he brings together the stark voices of victims, perpetrators and collaborators, all bearing witness – in very different ways – to the brutal crimes of Nazi-occupied Poland. The voices in these poems are woven together in a subtle and ruthless tapestry: farmers speak of recurring massacres as if they were seasonal crop cycles; German soldiers remember the droll image of desperate people foolishly running in circles as they are hunted down in the fields; a woman, about to be murdered, weeps in the forest with her son. The poems are frightening testimonies: short, distilled, often cool and cold. Particularly frightening are the narrations of the perpetrators and apologists, voicing in drab banality acts of sudden and devastating brutality. As Kwiatkowski warns: ‘We must not forget our tragic past because it might well return. The mechanism for its return has already been set in motion.’

(women are prized for their beauty)

women are prized for their beauty

men for the shadow of their long lashes

and poets for hiding flocks of aquamarine emotions

in a word

oblong night — under a kneecap moon

the poets walk the hills bursting with bone-white light

they kneel before the dead bird of silence

whispering prayers swollen with tropical pain

above them, opposite the motionless moon

mosquitos chirr their wings of dread

later it rains — and the poets return home

cradling word-eggs under their pea coats

(kobiety ceni się za urodę)

kobiety ceni się za urodę

mężczyzn za cień od rzęs długich

a poetów za to że w słowie

kryją ptactwo wzruszeń seledynowych

nocą – podłużną od smukłych kolan księżyca

wychodzą na bardzo biały światłem porosły pagórek

klęczą nad martwym ptakiem ciszy

szepcząc modlitwy nabrzmiałe tropikalnym bólem

ponad nimi naprzeciw nieruchomego księżyca

komary lęku brzęczą przezroczystymi skrzydłami

a potem pada deszcz – i do domu wracają poeci

pisklęta słów chowając – pod zmokłymi płaszczami

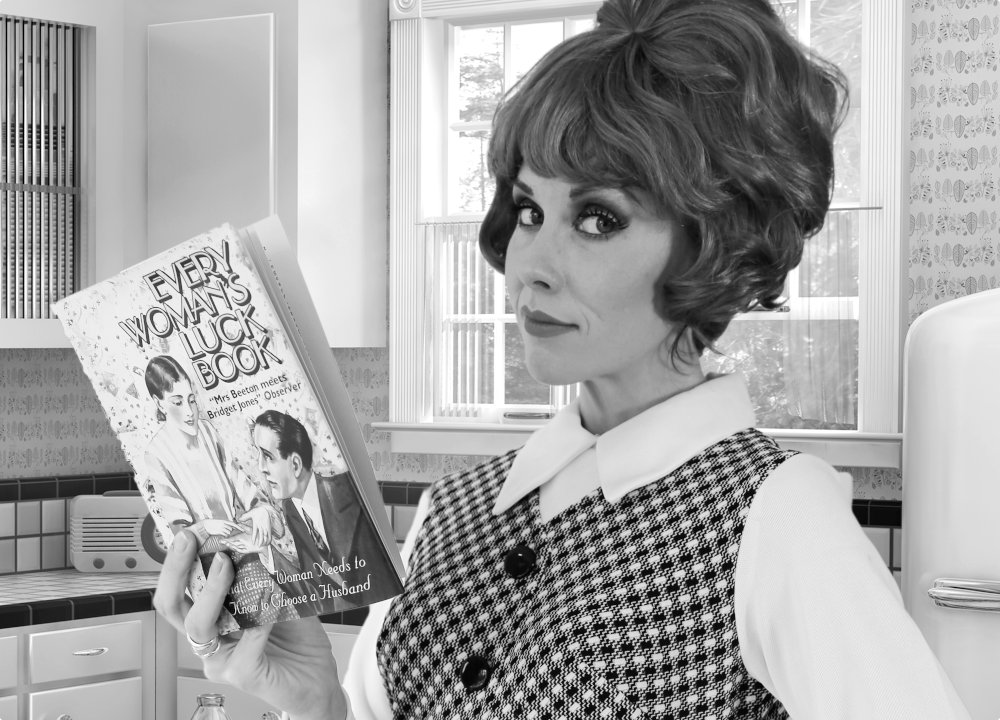

Perhaps I’ve spent too long in the self-help sections of bookshops, expecting to find the secret to long life and enduring happiness written down somewhere. As a poet, I am preternaturally worried about poetry running out on me: the inspiration drying up, the fun of it going out for a pack of cigarettes one day and never coming back, leaving me with nothing but a sink full of dishes and a manuscript full of melancholy poems about birds.

When I first read Ken Bolton and Peter Bakowski’s 2019 collaboration The Elsewhere Variations, I laughed. At first because of the humour – a truck sends the poem’s speaker into a ditch where they marvel at the names on the passing shipping containers ‘Tranter Parisian, Murray Australian Pie…Adamson and Fish… Judith Beverage, Bolton Drivel’ – but secondly, at the idea of two poets a generation older than me writing poetry to make each other laugh, as much as anything else.

I became interested in how Ken and Peter worked with one another, with an eye to discovering the conditions which allow poetic collaborations to remain fresh and full of humour, in the same way people examine the diets of people in Blue Zones, like Okinawa and Ikaria.

Pulling this interview together had its own, unique process, given that Peter and I both live in Melbourne, and Ken in Adelaide. Conscious of Omicron which was sweeping Australia in summer 21/22 and all suffering from Zoom fatigue, we decided to conduct the interview via email. I sent the questions to Peter who sent his answers to Ken, who sent them back to me. Like the poems themselves, this collaborative process took place ‘on the page’.

Throughout the two weeks of the interview’s lifespan, Peter emailed numerous black and white images of old race cars being driven recklessly around tracks with subject headings like ‘Ken Bolton races to the shops to get bread and milk’, and ‘Dom records Bakowski and Bolton on the home stretch’, I caught Covid at a wedding, and Ken very kindly corrected my spelling and grammar, which I was unable to blame on the virus.

Dom Symes: My first question is how did you become aware of each other? What was the early part of your relationship like and how did this develop into a working relationship – roughly up until when this collaboration became a possibility?

Peter Bakowski: I first became aware of Ken being the editor and publisher of Otis Rush and formally submitted poems to him. Ken accepted three in 1989 for Otis Rush #5. As one of my poems was about listening to Olé by John Coltrane, a correspondence started, then I mentioned that Helen and I were coming to Adelaide and could we please be billeted at Cath (Kenneally) and Ken’s, to which they agreed. While staying with them I perused Ken’s library of contemporary American poets and subsequently delved into the poetry of Frank O’Hara and Ron Padgett who became influences. There were subsequent stays at Cath and Ken’s with more talk about admired and influencing countries, music, and poets. In my 2014 poetry collection Personal Weather there’s a poem titled ‘Some lines are straight, some bend a little’ in which I praise both Ken and Ron Padgett’s ability to successfully detour in a poem. I sent a slightly different version of the poem to Ken, a version which mentions cufflinks as in my mind Ken had mentioned cufflinks in one of his poems. I suggested (without pressure) that Ken ‘respond’ directly or obliquely to my poem ‘Some lines are straight, some bend a little’ and he did with his poems titled ‘Phew’ and ‘Roadtrain’ to which I then responded. Our thought but not overthought accumulated responses to each other’s poems became a book length collection of poems, The Elsewhere Variations which was published in 2019 by Wakefield Press. Personally, I considered our fun and uncharted collaboration begun when Ken responded via a poem to ‘Some lines are straight, some bend a little’.

Ken Bolton: That’s about my memory of it too. It was a year or so on that I finally responded with two poems – and suggested two more by him then one by me would round it out as a unit of six, a ‘sixpack’.

Catching COVID-19 didn’t stop Sara Saleh from showing up to this discussion about poetry, place, and the place of poetry in the present moment. The exchange took place between 21 – 25 January 2022, quickly expanding into a 7,000-word conversation. The below interview reveals a condensed version of this chat without removing the essence of our exchanges.

Sara has walked many roads, traces of which are present throughout her published work: she is an eldest daughter, child of migrants from Palestine, Egypt, Lebanon, community organiser, Juris Doctor graduate, editor, future novelist, advocate, Bankstown Poetry Slam board member, Scorpio Sun, Virgo Rising, Sydneysider, multiple award winner, oat milk drinker, Banksia Bakery apologist, and poet.

Together, we explored Sara’s journey through the often-contentious world of poetry.

Angelita Biscotti: Hello Sara!! How has your day been? These have been interesting times, to say the least.

Sara M Saleh: Bed-ridden this week unfortunately, coming to you from day 10 of COVID, a stockpile of tissue boxes, vitamins, ibuprofen tablets, lozenges, and Hydralyte (COVID survivors toolkit). Yesterday I may have gone back to working from home too quickly, so I decided to give my body the rest and hydration it needs because clearly, it’s in overdrive. It’s been a precarious time. I feel grateful to be supported right now.

AB: I’m so sorry to hear that, Sara. Please do take the time to recover. The thing about mission-orientated humans is that there’s an incredible energy to push beyond the limits of what’s possible – and succeed. But the body and the mind have real limits. If you ever need a rest and recovery playlist, or Netflix recommendations to help with the lie-down period, let me know.

[A space between communications while Sara takes time to recover from the virus and continue with her other commitments]

AB: In a 2012 Cordite Poetry Reviewinterview, Emily Stewart asks Astrid Lorange: ‘What kind of a place is your Sydney? What are your key coordinates?’ I’d like to ask the same of you.

SMS: I don’t think I have ever been asked this question before and I love/hate it … probably because I love/hate ‘Sydney’.

I love it deeply. It is a city that has looked after and grown us, it holds so many people and places I love (Banksia Bakery is the best – fight me), the proximity of country – being in bodies of water, in nature, and of course, any place with books, including my local library, is often where you will find me.

But really people hold the coordinates down for me – my mentors and teachers and elders. Cup of coffee around the kitchen table with them is my starting point. You bring your problems and they have an answer for everything. There’s caffeine and accountability and a whole lot of mockery and laughter. It’s perfect Arab Aunty Energy.

But … I hate the city because how do we ignore the ugly side? The unsafe side? Taxing people out of their family homes, the profiling of us in department stores, the over-policing of black and brown communities and the ‘areas of concern’ rhetoric we recently heard during the lockdown, rhetoric that is an inevitable, logical extension of our elected officials and their racist policies, the fact that even public spaces like parks and stations and benches are made with the intent of keeping the public out! It’s cold and cruel. This is the social theory of space, architecture, and place as power … and it’s playing out daily.

Ultimately, it’s hard to reconcile anything ‘good’ with the fact that we are on stolen land. Hard to ever be truly at peace knowing this.

If people don’t see the cosmetic façade of the city – they are not paying attention. And that’s deliberate.

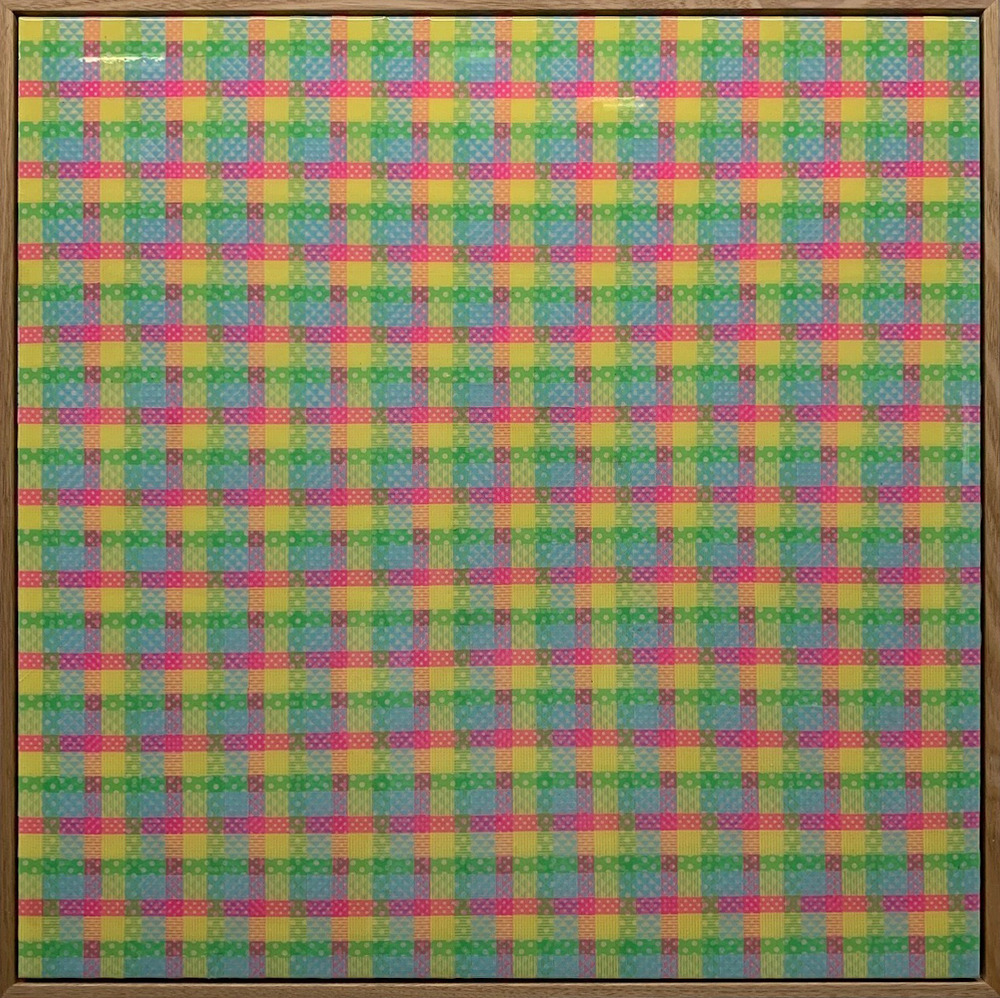

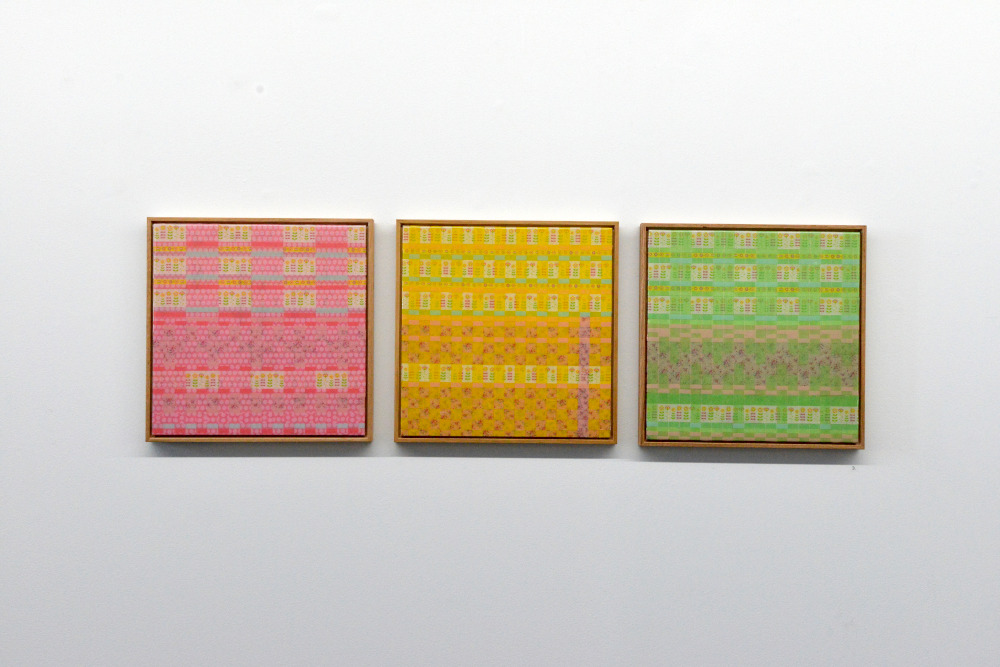

Maxxi Minaxi May | Tarting the Tartan | 2019 | 622mm x 622mm x 56mm (framed) | Washi tape (paper), glue and epoxy resin on board| Pattern Clasher (solo), Art collective WA

I am a multidisciplinary artist predominantly working with sculpture, mixed media, print and installation. By interconnecting representation, consumerism, and mediated culture, I remix perspectives of the Anthropocene, moving towards a more Symbiocene standpoint that is optimistic and harmonious. Themes related to the industrial, the everyday and the environment are frequently embodied through or by objects or collected materials that typify a Zakka (the savvy in the ordinary) aesthetic. Process and materiality are integral to my work. My art has a slick minimal or a decorative maximal quality, details resulting from repetitive action, components and patterns. Colour, play, humour, duplication, objects, craft, design, childlike nostalgia, humour and juxtaposition are often seen in her works.

Maxxi Minaxi May | Flower Patch – Morris, Ashley, Broadhurst, Marimekko | 2019 | 317mm x 317mm x 20mm (framed) | Washi tape (paper), glue and epoxy resin on board | Pattern Clasher (solo), Art collective WA

I am a pattern clasher. Mixing up designs in my clothing, my penchant is for the decorative. Combining collected boards, previous artworks and found objects with weaving, wrapping and decoupage, these works are quotidian, ornamental weavings – hinting at Maximalist, Zakka, and Expanded Painting theories.

This body of work (for Pattern Clasher) continued my research into Zakka art – a Japanese term, explaining when mundane ‘things’ are elevated, selected or used to improve lifestyle – both the ornate and functional. Washi tape is an example of this. Japanese masking tape, traditionally organic materials with glue, imprinted with varied colours, patterns, symbols and pictures, has become a staple of hobby-craft – a Western commodity widely used for DIY embellishment.

In the Pattern Clasher exhibition, masking tape is elevated from a media of ‘masking-off’ to become the actual ‘paint’ surface. Through these materials, I engaged with my affinity for stickers, stationery, global fashions, and fads that permeate culture. Materials such as Washi tape hybridise and augment popular cultural artefacts.

TextaQueen | Conveyor | Pigment ink on archival cotton rag | 420 × 597mm | 2016

As TextaQueen, I have been widely and wildly showing work for over twenty years in independent, commercial and institutional spaces around the world. I’m a queer, disabled, non-binary, second-generation Goan Indian settler, living on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation, in so-called Melbourne, Australia.

Known for using the humble fibre-tip marker to draw out complex politics of gender, race, sexuality and identity in detailed portraiture, I also investigate these themes via photography, painting, printmaking, video, performance, self-publishing, curating, music, writing and murals. Collaborating with other displaced and diasporic people, I examine our existence and empowerment in dis/connection to our own and others’ ancestral lands. With these intentions, I am currently creating TheySwarm, an artist residency for diverse and disabled artists, in Collingwood on Wurundjeri land.

Here is a selection of my work.

John Kinsella | Dante Optics Failure Purgatorio 15

What is more?

As part of my decades-long Graphology poems cycle, I have created many drawing-poems that (to my mind at least) exist between/around/across written text and visual images, and which hopefully test and blur semantic delineations and category definitions. Mostly, they exist in my journals, and co-exist with many different forms of ‘writing’ that possibly contextualises ‘legibility’.

I see ‘writing’ in everything around me, and do not think ‘script’ is the definitive form of ‘writing’. When I first read Ray Bradbury’s ‘The Illustrated Man’ at twelve, I thought that body images conveying/telling stories like movies seemed logical: when I see a ‘still’ visual image, it always moves, it is always active, and is always an act of writing and being written. I look at a ‘natural’ swirl in sand caused by wind, erosion, the movement of creatures, as being a form of writing: a record, a telling, of what has been and how that sand has interacted with the ‘world’, and how it has been interacted with.

Handwriting, something I do poorly but am infinitely fascinated by, always conveys more (to me) the more it breaks away from its system/s of constraint. ‘Scrappy’ handwriting is often an illustration of so much more than the symbols it’s supposed to replicate, and thus so much more than what it is intended to represent. Meaning exists in the incident as much as the intent. My work pages are often covered with doodling.

Also, over the decades, I have been writing different versions of Dante – Divine Comedy: Journeys Through a Regional Geography which responded to a specific region of the Western Australian ‘wheatbelt’ on Ballardong Noongar country; On the Outskirts which responded to Blake’s illustrations to Dante’s Comedy; and The Musical Dante which responds to musical interpretations of Dante (especially Liszt’s), but also bringing other music into vicinage with Dante’s Comedy. The Dante Graphology Drawing Poems are a fourth part of my engagements with the work of Dante (and in all of these works I also engage with other aspects of Dante’s life and practice, especially La Vita Nuova), and constitute an engagement with the historical approaches to Dante that impress on contemporary readers so much of their visual perception of Dante (e.g. Botticelli, Gustav Doré, Blake, the 1911 Italian silent film L’Inferno by Francesco Bertolini-Adolfo Padovan-Giuseppe De Liguoro).

But the Dante drawing-poems are mainly concerned with ‘reading’ the Comedy through a series of different personal lenses over a period of time. They are visual-temporal distortions. In an archive somewhere, there are a number of my earliest attempts at drawing-poeticising Dante’s Comedy, maybe done when I was around 22, which predate the beginning of the Graphology poem cycle by some years. Anyway, autobiographising aside, the drawing-poems around Dante exist as a kind of extension of what I’ve been doing for so long – try to find different ways into reading Dante, especially what I call ‘the ecological Dante’.

Here is a selection of Graphology Dante Drawing Poems. I have created many dozens of such works in which text is either overtly part of the images, or is sublimated through signs or even drawn over to make it ‘vanish’, with traces remaining in abstracted ways. Or, the images are words. Really, the images are an orthography – they are ‘how’ the words come out in this reconceptualising: a rebus, a semaphore, a denial of any primacy of ‘written language’ that denies the separateness of ‘illustration’.