Where We Are is about place (where), people (we) and the present tense of existence (are). The place could be two, Scotland and Australia, but really it’s one: wherever we find ourselves. The people could be poet, family and friends, poet and reader, or all of us on this drowning, burning earth. The present tense could be this moment, or a past so intensely remembered, or a future so powerfully imagined that past, present and future are simultaneously here.

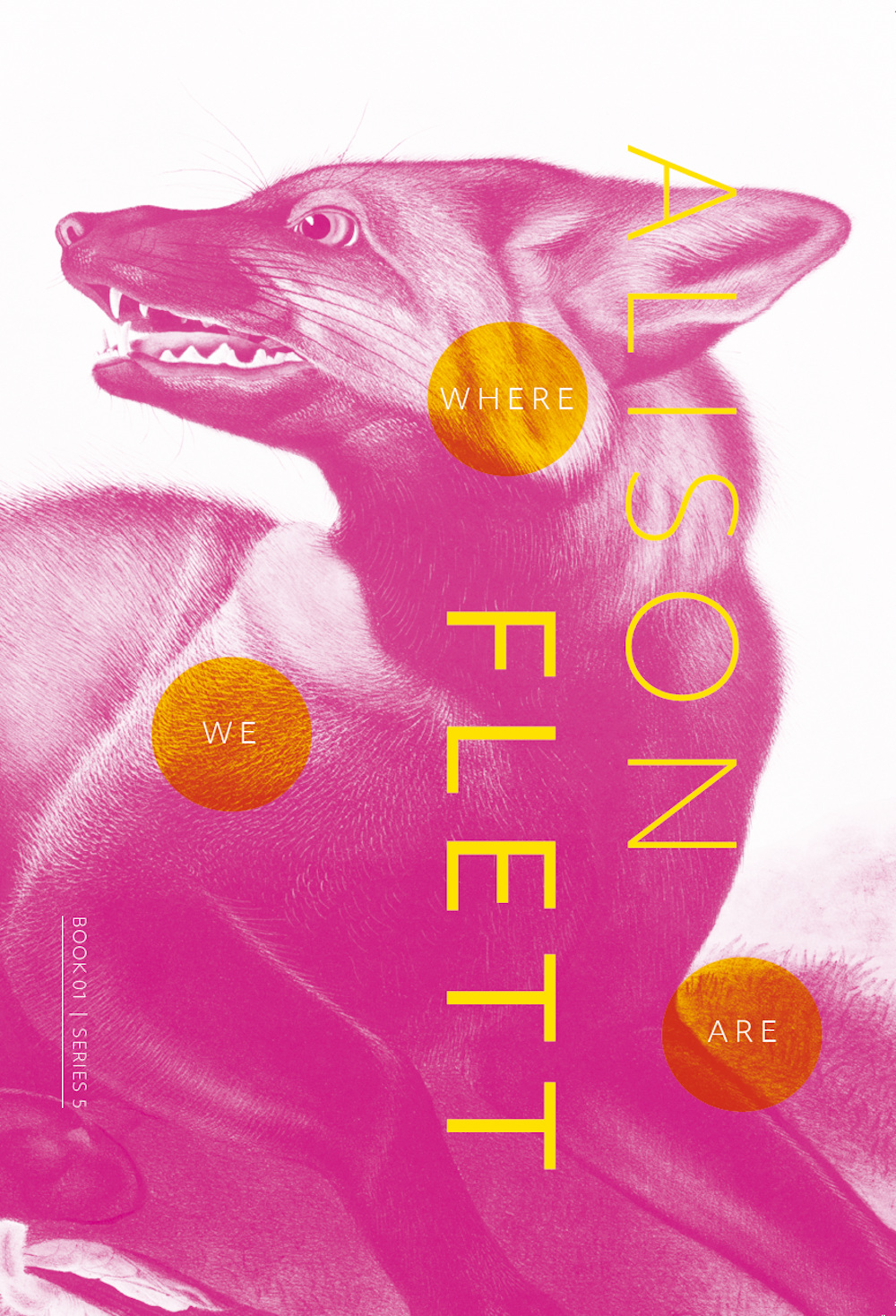

Conditional responses to the poems seem not only possible, but necessary. There’s much that slips in and out of light, and Flett’s poems have a zero-sum gaze: where there’s not light, there’s darkness. In ‘Wherever This Is It’s Where We Are’, there is ‘thedarkthatsurroundsus’ and ‘the labyrinth of dark streets’ and ‘the crow’s black heart’. There are the hunting shadows of Tenebrae, the service of falling darkness. And the fox’s ‘wet black pavements’ and ‘red-black fur’ and ‘black-red eyes’ in ‘Semiosphere’ (shades of Terrance Hayes’s ‘black-eyed animal’.) The fox slinks in and out of darkness, in and out of sight and comprehension. Darkness isn’t always threatening – it’s just that we can’t understand inside it.

We read some of these poems as stories, because inventing narrative lines – that may not be there – makes sense. ‘Seen Through’ is six window views, from living room to B&B to Hilux to tent to pub and home. We read the ‘to’s into this, they’re not written in, making it a traveller’s tale, a road trip up the ‘Oodnadatta stretch’ and on to Uluru and back. ‘Still Life in Library with Keys’ might seem like a painting, as in Kelman’s version of Cézanne’s ‘les joueurs’, but it’s alive – it’s still life, not a picture of it. It’s the story of a poem being written, or unlocked, or emerging, among the millions of words shelved in the library. Brand-new text born out of old but also out of the library’s pigeons, passers-by, line dancers, self-talkers, soup-eaters. ‘Nothing but noise’? Nah, we hear poetry.

Tomas Tranströmer haunts Irvine Welsh in ‘Liminoid’, a prose-poem yarn in Edinburgh Scots: ‘a tousie bunch’ of partygoers glimpsing a fox (that doggone beast again!) out of the corner of an eye. There you go: a second Scottish prose writer, but not a poet in sight, because there’s no glimpse of contemporary Scottish poetry here. Twenty-five years ago, Flett’s work moved in tight formation with Tom Leonard, Margaret Hamilton and Ian Hamilton Finlay. Now, having flown half way round the world, she’s in an orbit with Ken Bolton, John Forbes, Jill Jones, Eileen Myles.

In ‘There Is a Bigger Telling That Moves Around the World’, words make the world go round: language is ‘the ultimate thump thump’. ‘Telling’ is counting, what a teller does after elections. The vote here was a choice between ‘a song of YES’ and the ‘cold NO’ which won. But there’s hope for YES next time because ‘we have all the words’. Those Australians at their barbecues talk so much that words form a ‘tumulus’, ‘mounded over us’. The great heaps of ancient civilisations are tells. Is that what the builders are shouting about? When we read ‘something/that might have been done was not done’, we catch the echo of Scotland’s many hill fort duns – Dunbar, Dundee Law, Dùn Èideann. The story goes round: we could have built a castle, but cold NO won, and we didn’t. Still, the builders are busy, they’re opening the ground. Maybe they’re digging to Australia. Or maybe I’m digging up far-fetched meanings. And? You want to make something of it? Go ahead: build.

Here we are with a poet who knits intricate patterns of sound and image, line to line, poem to poem; a poet who pays attention to W=h=e=r=e=W=e=A=r=e and makes it heartbreaking, breathtaking, beautiful.