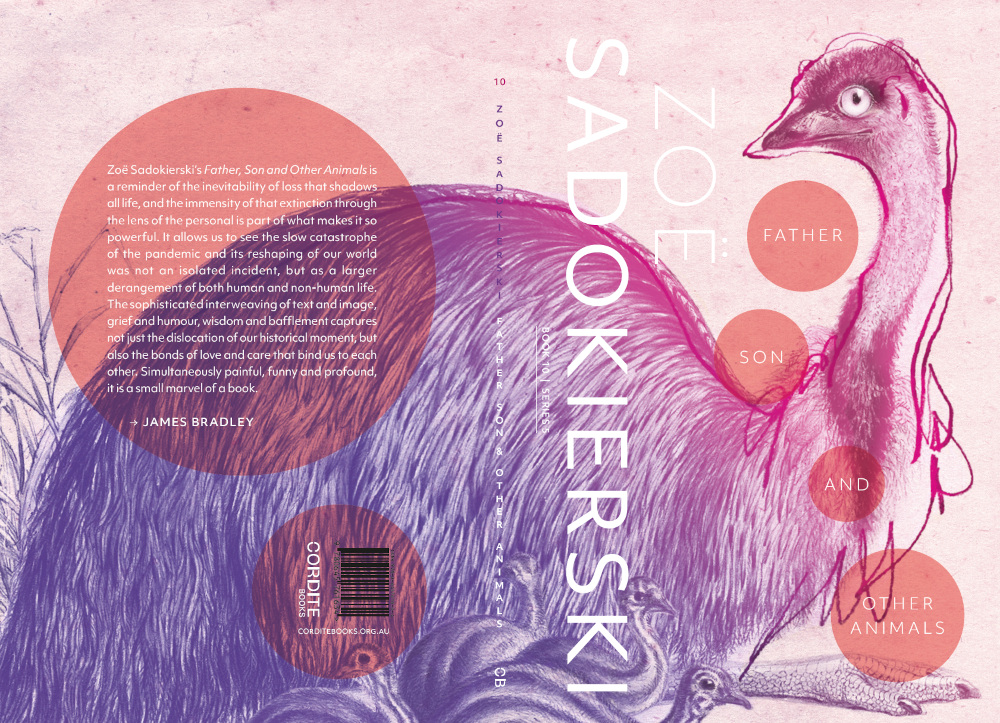

Zoë Sadokierski’s Father, Son and Other Animals opens with a moment of disconnection, as she describes her father’s tendency to retreat into himself when they are together, disappearing into imaginary golf practice. ‘Sometimes when I’m talking to Dad, he’s not there. I look over and see that he’s gone.’ In keeping with the book’s broader interplay of humour and darker concerns, Sadokierski uses it as an excuse for a moment of black comedy. ‘When he’s like this, I could say anything,’ she continues. ‘Dad, I’m really struggling being a working parent. I’m drinking at breakfast.’ But, like the animal skull he later presents her, her father’s distraction prefigures the larger absence that will eventually overtake him, transforming the scene into a sort of memento mori, a reminder of the inevitability of loss that shadows all life. And, no less importantly, it suggests a larger kind of extinction, one summoned up by the mute images of feathers and bones sketched alongside the words.

This refraction of the immensity of loss and extinction through the lens of the personal is part of what makes Father, Son and Other Animals so powerful. In the same way its sections move from historical events to the minutiae of parenting during the pandemic, the glancing and fragmentary nature of its structure, and the marrying of word and image, allow it to give shape to the inner dimensions of unsettlement and loss that define life in the Anthropocene.

Some of these dimensions concern an awareness of non-human and more-than-human presences, and the unsayable grief of the gaps their disappearance leaves in the world. Father, Son and Other Animals allows us to glimpse the degree to which the slow catastrophe of the pandemic and its reshaping of our world was not an isolated incident, but part of a larger derangement of both human and non-human life that is being driven by human activity.

Sadokierski is eloquent about the fears and uncertainties of parenting in a time of crisis, capturing the degree to which parenthood is a process of unsettlement in which we are unmade and reassembled, our former selves suddenly out of reach and strange to us. Likewise, children reveal themselves to be fundamentally unknowable, their lives as inaccessible to us as those of our parents.

These ideas echo through the book, reflecting off each other in unexpected and often startling ways. An accident during a swim in Sydney Harbour offers a reminder with the corporeality of the body, underlining the murderous potential of the axe wielded in the burglary in an earlier section. A description of the fate of the dwarf emu collides with the loss of a plastic KeepCup in a nature reserve. The unthinking violence of the natural world is balanced against the smaller detonations of family life. And shadowing all of them is the unspoken brutality of Indigenous dispossession.

I want more books with the complexity and intelligence of Father, Son and Other Animals. Not just because we’re going to need them if we’re to find ways of processing and commemorating the transformation of the world, but because we need to find ways to live and celebrate as well as to mourn and rage. The book’s sophisticated interweaving of text and image, grief and humour, wisdom and bafflement does just that, capturing not just the dislocation of our historical moment, but also the bonds of love and care that bind us to each other. Simultaneously painful, funny and profound, it is a small marvel of a book.