After Naptime by Chris Edwards

Vagabond Press, 2014

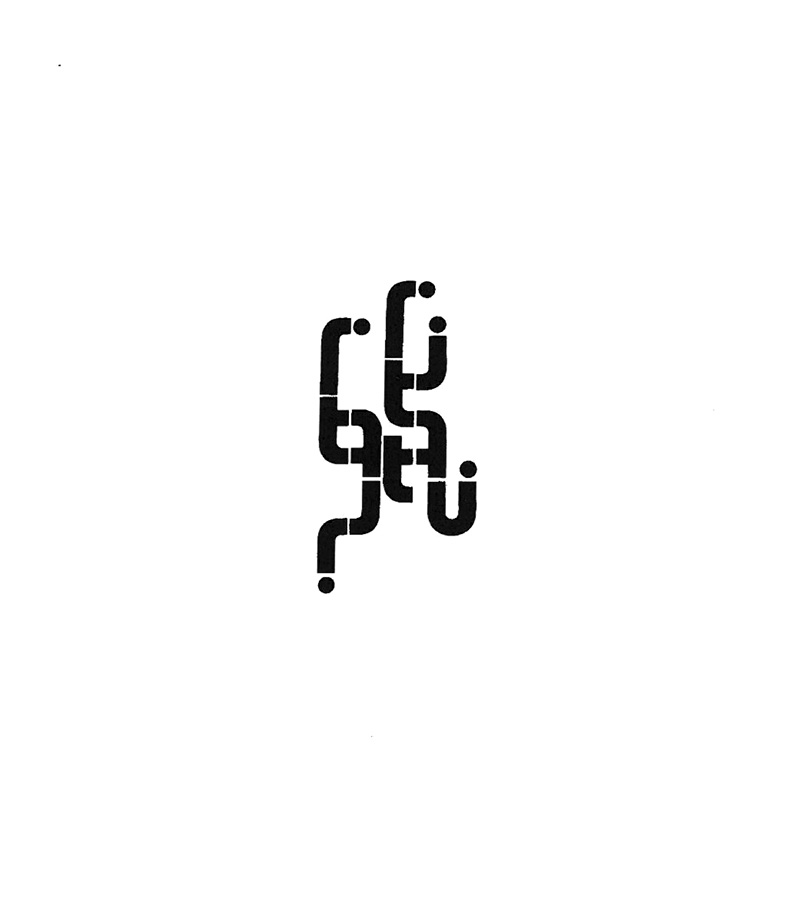

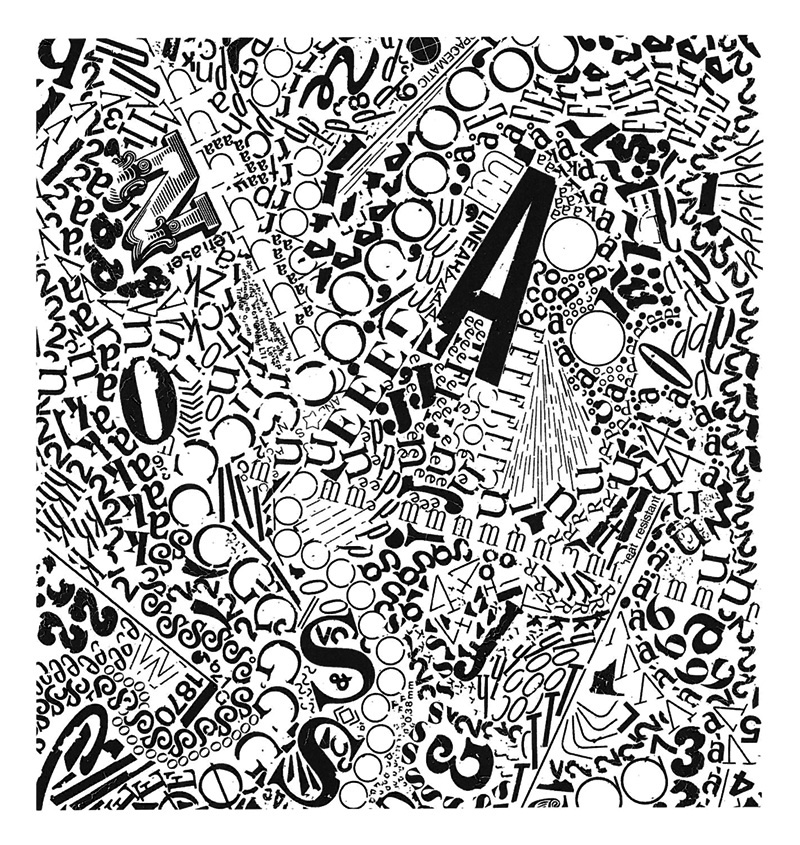

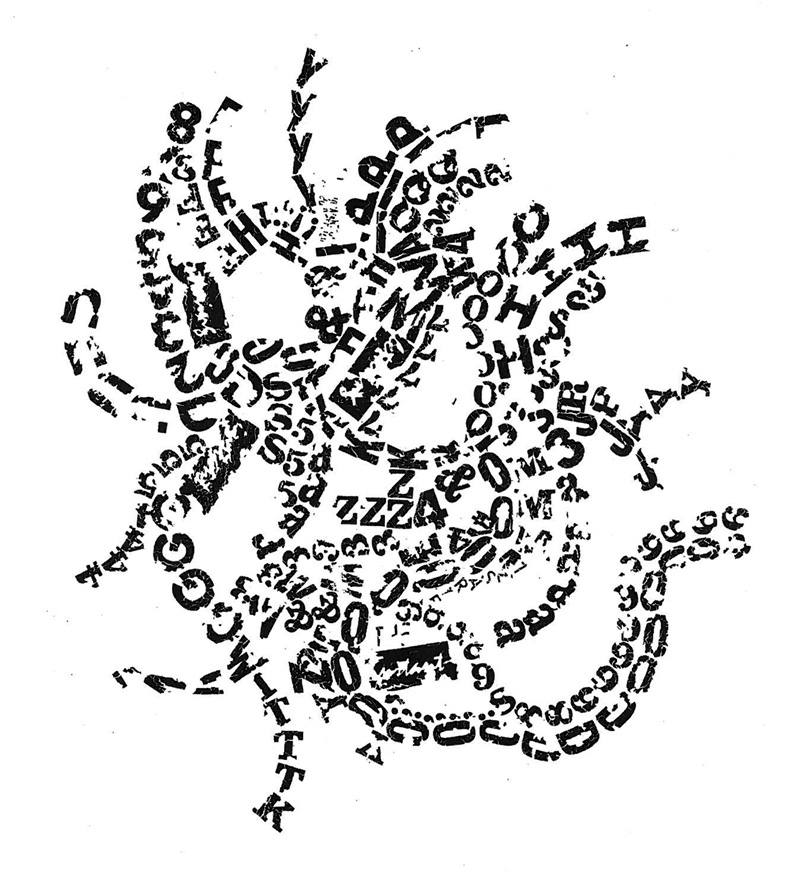

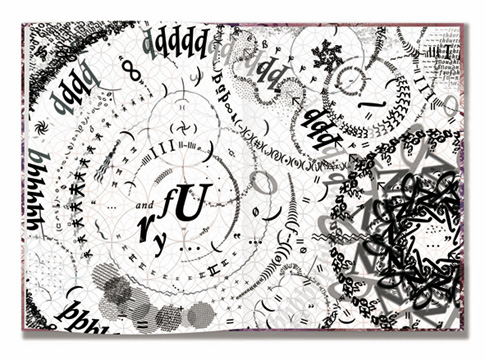

PREFACE Page references to Chris Edwards’ “A. N.”* are imposed—i–viii (Front cover–Contents), 1–22 (Text), ix–xiv (Sources–Back cover)—according to its Contents’ functionally reflexive bracketing. The central text operates, in the majority, through ten two-page spreads of apparently sourced (see “Sources” (x)) and assembled language and b/w illustrations and clipart that ‘invite’, through formal, typographic, scalar, and iconic cues, a handful of mutually interruptive reading strategies to convey a loose, visually intensified, and theatrically structured ‘story’ whose principal driver I interpret as a kind of adaptive, paranormal virus invested with a relationship to sexual desire by the detective-generic narrator. Although a source list is provided, any restrictive or procedural ‘commitment’ to these texts is indeterminate.

PREFACE TO CORDITE EDITION

REVIEW [ … ] As adolescents know, ‘multistability’ is a non-durable baffler of liquid, ‘open-ended’, parental inquiry; without recourse to a sophisticated rhetorical composition, lethargic or unresponsive to the face of interrogative contingency and capable of sublimating registrations of referential ambiguity upon formal self-closure, real (situational) escape is required, lest the “subnormative” creativity of a protective testimony—its provisionally illegible honesty—manifest as the ‘joke’ it virtually is, bringing “forward what is hidden”: the fact of an alternate stability (Virno 73, 79). This dissemblance—a demotic, interpersonal mode of InfoSec—is not the manipulative ‘simulation’ of a fiend or apathetic amoralist; it manifests, instead, within an aghast, puritan logic where any ‘omission’ that takes place is, crucially, of the (‘called-for’) lie; it is underwritten by both a tacit accusation that an inquirer would have the dogmatically honest subject generate falsehoods and an understanding that any dismissal of this integrity as duplicitous or legally spiritless (refusing mediation by operating ‘to the letter’) precipitates a (claim to possess a) ‘right to know’ that itself founds ‘spiritless’ (despotic) law. Although the youth-dogmatist requires that hir testimony “sustain ambiguous readings”, a capacity attributed to the “gestalt principle” of multistability and co-terminus solely with an absence of vivid feedback that continues to characterise circulated texts, s/he further requires that “all the elements of the work [be] directed toward a single reading of it”, such that it both enunciates the ‘case’ according to ‘juvenile’-personal law (or an absence of authority in the mature world) and remains singularly interpretable (‘closed’) by adult power as innocuous (e.g. ‘I am going out’; ‘just some friends’; ‘yes’) (Drucker 9; Hejinian 42).

Is it an error to interpret proffered ‘adult’ dissemblance and multi-stability with provoked vernacular-‘juvenile’ security frameworks? Consider, for example, (a reading of) Melanie Klein’s speculative account of infantile defence mechanisms. Upset by internal agitation, possibly due to an occasion of negative relations with the (~ only) object, I defensively project (spit up) or externalise this ‘negativity’ onto (some element of) my surrounds; to protect myself from the negativity now in my environment, I defensively introject (consume, devour) this negativity, internalising it as an agitation; upset by internal agitation ( … ). Although this wreath of logic appears to be founded, in part, on an irrational column of fear, that of retributive consumption of the infant by the breast-function (subtended by the hybrid-parent-function), Sianne Ngai’s analysis of the ‘cute’ as “an aestheticization of powerlessness” grounded by an “aggressive desire to master and overpower the cute object that the cute object itself appears to elicit”, a “tie between cuteness and eating”, and edibility as “the ultimate index of an object’s cuteness” evokes a genuine, if disavowed, provenance of terror subject to infantile intuition (64, 78–79). Something does want to crush and consume the pseudo-entity and it is precisely what s/he has identified, through hir first act of differentiation, as a threat.

(Fig. 1) Concordance pp. 1–3.

(A) 1, 3; (a) 1, 1, 2; (aah-choo) 1; (accompanied) 3; (acquainted) 2; (actually) 1; (all) 1, 3, 3; (already) 1; (amazed) 3; (among) 1; (and) 1, 1, 1, 3, 3, 3; (anti-) 3; (arranged) 3; (arriving) 2; (as) 2; (ask) 3; (at) 2, 2, 2, 3; (B) 1; (be) 2, 3; (be-keepers [sic]) 2; (because) 2, 3; (becoming) 2; (bee) 1; (been) 1, 2, 3; (began) 3; (begin) 2; (believe) 2; (born) 3, 3; (branch) 3; (but) 1, 1; (by) 1, 3, 3, 3, 3; (catalogue) 1; (certain) 1; (checked) 1; (civil) 3; (clock) 3; (Clockwise) 3; (closed) 1; (coming) 2; (communication) 1; (companion) 2; (corner) 1; (cottage) 2; (cow) 1; (cry) 3; (day) 1; (deposited) 1; (destined) 2; (Detective) 1; (did) 3; (discovered) 3; (during) 1; (e) 1; (either) 3; (Enter) 1; (exhaustless) 1; (falsified) 3; (father) 3; (fifteen) 1; (first) 2; (flax-plant) 1; (fling) 3; (followed) 1; (for) 1, 3; (garden) 2; (gender) 3; (germs) 1; (ghost) 1; (ghosts) 3; (gifts) 3; (gone) 1; (had) 1, 2, 3; (have) 1, 3; (having) 1; (head) 2; (her) 1; (here) 2; (highly) 3; (his) 3; (hours) 3; (human) 1; (I) 1, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3; (if) 2; (in) 1, 2; (inarticulate) 2; (inclination) 3; (informed) 3; (inhabited) 3; (innocent) 2; (inquiries) 3; (Inspector) 1; (iron) 1; (irritated) 1; (is) 1, 1, 1; (it) 1, 2, 3; (king) 1; (Lady) 1; (less) 1; (letter) 1; (life) 2; (little) 3; (low) 3; (m) 1; (made) 1; (manner) 2; (me) 1, 2, 2, 3; (means) 3; (meet) 2; (Mercury) 1; (merits) 1; (mind) 3; (mirror) 1; (money) 3; (more) 2; (my) 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3; (name) 3; (No) 1; (no) 1; (nothing) 2, 3; (o) 1, 3; (of) 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3; (On) 2, 3; (on) 2; (open) 3; (or) 3; (our) 2; (out) 2; (ow) 2; (oyster) 1; (papers) 3; (person) 1; (personally) 2; (pockets) 1; (point) 2; (posting) 1; (prearranged) 2; (price) 3; (purse) 1; (question) 3; (result) 3; (retreat) 3; (ringing) 1; (sailors) 1; (sculptor) 3; (sealed) 1; (second) 3; (secondly) 3; (see) 3; (servants) 3; (shall) 3; (shared) 3; (she) 1; (sheep) 1; (silkworm) 1; (simultaneously) 3; (small) 3; (so) 3; (something) 2; (sounds) 2; (spirits) 3; (stare) 2; (still) 1; (successful) 3; (telephones) 1; (Temple) 1; (that) 1, 2, 3, 3; (The) 1, 1; (the) 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3; (their) 1; (Then) 1; (Therefore) 1; (this) 2; (those) 2, 2; (Thousands) 1; (To) 2; (to) 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3; (touched) 3; (turn) 3; (turned) 1; (unlucky) 2; (until) 3; (up) 2; (upon) 2; (verified) 3; (virulence) 1; (w) 1, 1; (wardrobe) 3; (was) 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3; (were) 1; (Whether) 3; (which) 3; (whose) 1; (with) 1, 3; (years) 1; (yes) 3

(List 1) Unordered list of plausible reasons for the ‘meaningfulness’ of variable letter capitalisation (‘a’/‘A’) in the title leading to its unreliability as a piece of citation *[“after Naptime” (i), “AFTER NAPTIME” (iii), “after Naptime” (v), “After naptime” (vii), “AFTER NAPTIME” (8), “After Naptime” (xiv)].

List 1. Edwards is an editor according to external biographical notes and is credited here with “design and typography” (vi); the uniformly lowercase utensils in a landscape (2001) is consistently cited as such and listed in an “Also by Chris Edwards” section (iv); the sometimes non-standard lowercase a following the colon in A Fluke: a mistranslation of … (2005), listed in the same section (weak); (?).

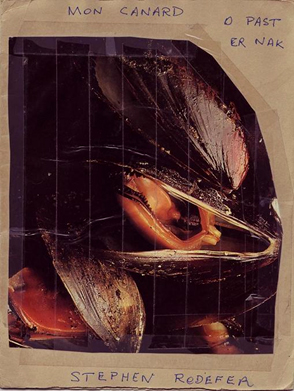

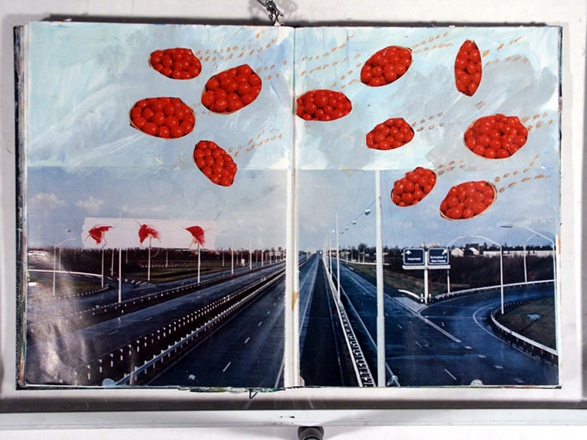

A quality-luxury continuum, invoked by the scarcity of an Edwards-‘contacted’ edition—“a limited edition of 111 copies / numbered and signed by the author” (xii)—and the sub-titular phrase “profusely illustrated”—gleaned, it seems, from the final provided source title—is interrupted by the blatantly ‘poor’ reproduction of an oil lamp image on the cover (i) and title page (v). Outline asperities, beyond prefiguring a ‘real’ underlying lack of smoothness and enclosure that will be taken up as a key predicate of all content within the text, preyed upon there by a phantasmic-biological entity represented by pictographic and illustrative collages of ‘enhanced’ (close-up) fibrous nerve endings and ‘distant’ (small) human-animal bodies, confirms that Edwards’ materials have ‘passed through’ the bitmapping of digitalisation; ‘edges’ of elements appear jagged because of resizing rather than collage-‘cutting’ issues; included visuals exist as transmittable image files, elsewhere. Nine dots left open for edition numbering (“number . . . . . . . . . of” (xii)) ‘call back’ to the coupon dashes-and-scissors that frame the text’s preface (1)—embedded prompts for physical transformation of the object by the reader and author-publisher-function respectively, the latter of which, if intended to be constituent with Edwards’ hand, takes up the commercial-language gesture of an ‘I’ speaking of ‘oneself’ in third person (“signed by the author” (xii)); this copy states, for example, that “‘Edwards’” is “the narrator” when narration and the perspectival accounting of emotional investment implied by this position are occupied from the outset by an ‘I’ that references an “Edwards” (e.g. “[ . . . ],’ says Edwards” (9)), a figure or position that continues to potentially, jokily, multiply (e.g. “E at work” (7) or “Ed. Note:” (16)) and a reference to the common inter-community practice of providing requested biographical notes in third person.

Drucker, Johanna. (2009). ‘Entity to event: From literal, mechanistic materiality to probabilistic materiality’. Parallax, 15:4, 7–17. Pdf.

Drucker, Johanna. (2012 [1984]). On writing as the visual representation of language. New York Talk, NY, June 5, 1984. PennSound. Mp3 file.

Hejinian, Lyn. (2000). The rejection of closure. In The Language of Inquiry. University of California Press. Print.

Mitchell, Juliet, ed. (1987). The Selected Melanie Klein. Simon and Schuster. Print.

Ngai, Sianne. (2012). Our aesthetic categories: Zany, cute, interesting. Harvard University Press. Print.

Scalapino, L. (1993). Objects in the terrifying tense longing from taking place. Roof Books. Print.

Virno, P. (2008). Multitude: Between innovation and negation. Semiotext(e). Print.