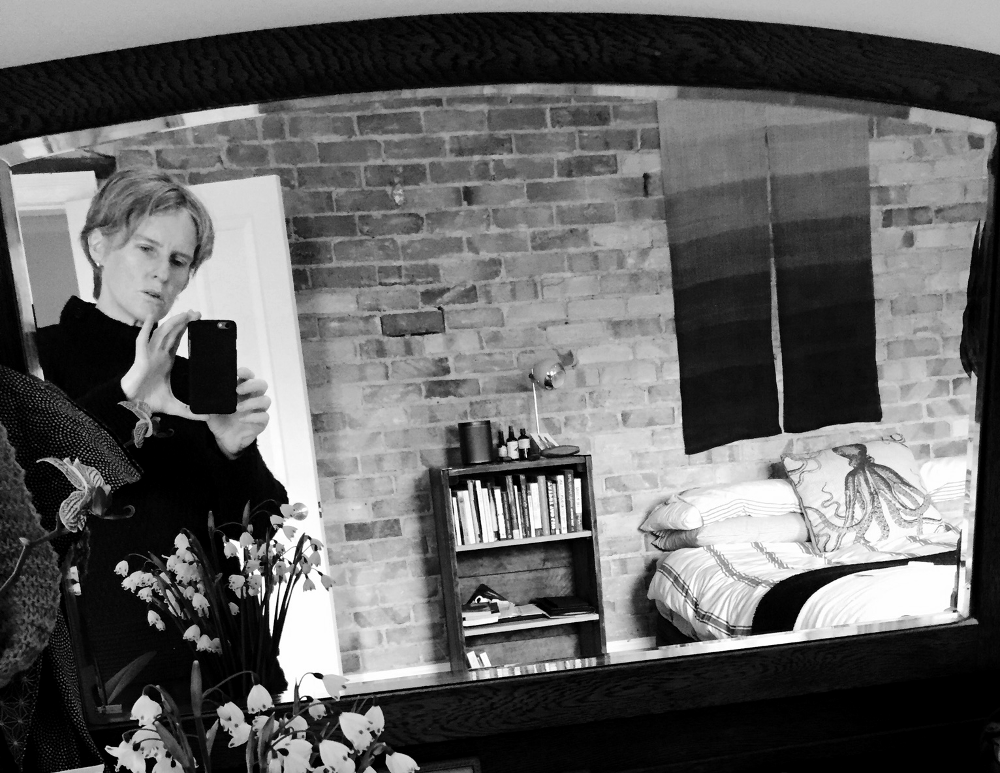

The central drama of post-internet poetry is that of disclosure, confession and self-creation.

– Charles Whalley

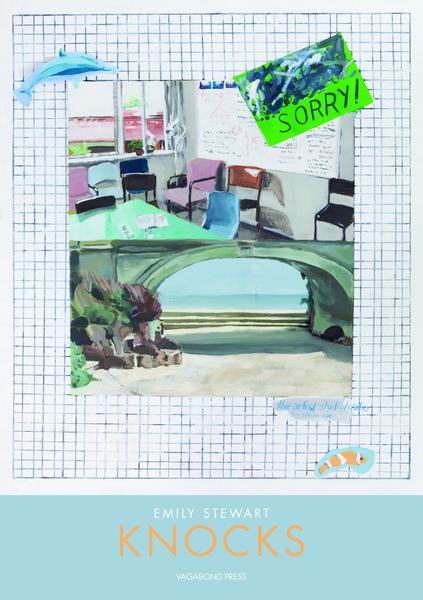

Charles Whalley’s essay on post-internet poetics ‘This has been a blue / green message exiting the social world’ takes its title from a Sam Riviere poem, which makes me imagine ‘blue / green’ text messages bubbling like algae blooms on a mobile phone. If communication and sociality are nothing new to contemporary poetics – a conversational style pervaded many of the poems by Australian poets who have been writing since the 1970s that I cut my teeth on, poets such as Ken Bolton, John Forbes and Pam Brown, themselves influenced by the earlier ‘personism’ of American poets such as Frank O’Hara and Ted Berrigan – it remains in 2016 where so many of our conversations happen online (whether directly messaged or indirectly posted). Digital media has become an intrinsic intercessor not just in the expanded ‘digital literary sphere’ (Simone Murray 2015), but also aesthetically.

When I chose the theme of ‘Confession’ for this issue, I wanted to see what meaning it might yet have in our contemporary digital dialectic, where we must increasingly navigate and present ourselves and our lives in a way that is, at once, privately public. After all, this ‘knowing’ sense of constructing a self for consumption has always been the domain of confessional poetry (think Sylvia Plath), and I suspected that there would be confessional poems galore in our ‘over-sharing’ era. It’s a conversation we are dropped right into in Eva Birch’s ‘The Last Time’, a psychogeography of trauma, memory and digital communication:

Keeping up with

Keeping up with all the different types of abuse in Melbourne

my brain runs out

I can’t remember anything

except

every email and every text every ex sent

While Sam Riviere has gone on to use some decidedly non-lyrical techniques – his most recent book of seemingly semi-confessional poems, Kim Kardashian’s Marriage, is actually entirely unoriginal (none of it self-composed) – when I read his earlier collection, 81 Austerities, I was struck by how, at heart, I sensed a sexually anxious, heterosexual male persona, no matter how mediated. Indeed, mediation can seem to promise a desired remediation, as in ‘Save’, his poem in this issue:

… and in her bed

luxuriously blurred, I finally feel able to author an

anonymity that is believable.

Justin Wolfers’s ‘Backchannel Norms’ picks up the theme of masculine insecurity in lines so short they could have been composed on a phone screen:

I’m sorry, I

tell her later,

sorrier than

I can say

into such a

tiny chat box

The persona of this poem is called ‘Justin’, which suggests the kind of flat affect that Oscar Schwartz argues in his essay ‘Can I Have your Attention Please? Poetry in the Age of Social Media’ is familiar to readers of Alt-Lit (a loosely defined literary community that draws its motifs and modus operandi from online culture). It’s at once ‘detached, unaffected yet existentially absorbed and emotional’ (Schwartz). I’m not sure if Wolfers is interested in emulating or parodying poets like Tao Lin in his waxing anti-lyrical about a hypothetical long poem that

… simulates

the feeling of

disappointment

without delivering.

The poem acts as a meta-poetic orobus while performing what it is otherwise about.

Kafka once wrote,

I tell her, I solve

problems by letting

them devour me.

Yeah, she replies,

But I don’t think

he meant that

as advice

It’s a prime example of an on-going conversation with recent American and UK poetics happening in Australian poetry, engaging with established tropes such as gender, poetry’s relationship to film, music, literature and popular culture, and most compellingly, the question of voice.

Justin, a linguist would say,

violates backchannel norms.

While it seems there will always be the obligatory male masturbatory poem, it’s herein updated for the end of the anthropocene in Adam Ford’s ‘I’m Worried That My Increasingly Complex Shower Masturbation Routine is Unethical Because of The Amount of Water I Use’.

One criticism of Alt-Lit has been along gender lines, though in this issue the post-internet confession is decidedly queered, as non-binary poet Rae White writes in ‘tweets I never published’

& there are days i hate

polyamory – it makes me

more tired than i thought possible

Relationships between self and other also provide the fodder for some other younger female poets new to publication in Cordite Poetry Review, like Alice Chipkin, whose ‘Lung Rubble’ charts the demise of a same sex relationship –

we hold hands and walk back to st kilda. I stare at the kids staring at us. Let

them think we are girlfriend & girlfriend. it’s not a lie, just fucked up

chronology

and Talia Chloe, a 21 year old poet whose list poem ‘21 Ideal Dates’ is riddled with projected anxiety such as solastalgia –

Ideal date: you tell me about meromictic lakes and melting glaciers. I am

nervous and say that you would make a pretty glacier.

though Ellen van Neervan’s ‘Water on Water’ ends more affirmingly:

I am loved.

Other poems are more engaged with the self (away from others) such as Ali Jane Smith’s anti-social ‘Clodhopping’ and Jill Jones’s riposte to contemporary culture ‘My Skeptic Tremor’. Some are built around the refusal of the self (Ann Vickery’s ‘On Not Giving an Account of Oneself’) while others compile portraits of others, such as Kathryn Hummel’s ‘Being Astrid Lorange’:

I’m round like a kitten and my kitten teeth too.

So soft, my white jumper like any boy’s beard.

This issue compiles work that is decidedly diverse in gender, sexuality and culture, and includes ‘Making Instant Noodles at the End of the Rainbow’ by Indonesian poet Norman Erikson Pasaribu (translated by Tiffany Tsao) writing a eulogy for a transgender friend. In another gastronomical ode, Jamie Marina Lau’s ‘Disgusting Landscapes’ creates an abject cornucopia that begins ‘The West has been kneed in the gut’ and ends ‘Some dairy wobbles’.

The relationship between music and the lyric is another strong theme. There’s the ‘Norwegian nu-disco’ of Alexandra Schnabel’s ‘aphex twin grin or, r.i.p Mercat’ through to Gareth Jenkins’s ‘There’ll always be music’ making the obligatory Leonard Cohen reference (turning him hygge!)

whom she’s translating into Danish

with the writer’s group she’s formed in the asylum.

In the year that Bob Dylan wins the Nobel Prize, Toby Fitch has composed ‘Illiterature’ with a nod towards Kurt Cobain and Ian Curtis, and for 80s fans there’s New Zealand poet (in an issue featuring the work of a number of both Maori and non-Maori poets from New Zealand) Stephanie Christie’s ‘Unfinished Objects’:

Today, hearing Classic Hits, I realised what’s going on in

the lyrics to ‘Total Eclipse of the Heart’. I had to step out

of my place in line and hide in an aisle with the diaries.

We’re living in a powder keg and giving off sparks.

More traditional confessional subjects, such as grief, are also covered. Kate Lilley’s ‘Mortalities Memorandum’ is about the death of her mother, Dorothy Hewett.

Name a prize after her call it the sad and lonely prize