In another poem, Nguyễn Thị Hoàng Bắc reverses the situation of women who are by nature nailed into the figure of ‘she whose piss cannot surpass the tips of grass’ with a bold reinterpretation of this act. The poem ‘Tips of Grass’ first appeared in Hợp Lưu in 1997, and was later reprinted in the aforementioned anthology, breaking out a scandal of feminist ‘pissing poetry’:

Tips of Grass

the sound of piss

dripping drops

trickles in a toilet

warm liquid quivers

amber

streaming from my body

yeah

I’m a lady

the category of she whose piss cannot surpass the tips of grass

now

able to chill on the impressive throne

in the future won’t it be that we

slacken our pot bellies

a trickling like rain

wind’s game trembles the grass tips

This poem stirs much emotion for me; scornfully proud and truly intimate, mocking and sympathetic, tender even, it’s both a challenge to and a confession of one’s plight. The image of a woman listening to the sound of her own trickling piss, the image of a quivering amber liquid streaming out of her body, her self-described ‘impressive’ posture on the toilet, and the re-performance of her bodily gestures without the slightest bit of shame all produce the effect of a coquettish playfulness, of a comic and intelligent negation of feminine principles that tend to govern by means of a masculine gaze and female allegiance. The pleasure of playing with one’s own excrement (piss), the self-observation and the exhibition of a private space (the bathroom) creates a complex of images and acts that reveal naturally wild and freely expressed joy – perhaps quite different from the works using similarly “dirty” materials in contemporary art in order to manifest ambitious and more shocking ideas.One is reminded of Merda d’Artist / Artist’s Shit of Pierre Manzoni or Shit Show of Serrano for example. The grotesquely imagined and exaggerated image of a woman ‘slacken(ing) (her) pot belly’ as a result of ‘chilling’ on the toilet, producing a ‘trickling like rain’ liquid stream, perhaps can be read as an allegory of disobedience, but it is one with the sense of lightheartedness leading to wonderment. As well, it would be impossible to comprehend all the nuances of this poem’s humorous images without reimagining the more traditional daily space of Vietnamese women in old villages, where the modern bathroom had yet to appear and toilets might be a deserted space in the middle of a field. Thus, privacy performed in the middle of a public space, as opposed to a toilet’s private space in modern life. Following this thread, the poem creates a contentious liminal space between private and public, traditional and modern, rural and urban, and the act of a woman’s gazing at herself here is clearly not detached from a sense of reinterpreting the past and the space of the past. If this process of unmasking is understood as a form of antagonism, then it is an attack with many targets, among which include not only the masculine gaze and reinterpreted societal structures, but the living spaces themselves, and further, a tacit reinterpretation of the oppressions embedded in language. The act of writing poetry, the self-revealing of one’s condition through language, is not a treatment for the individual psyche. Rather, it can incite further acts of upstream swimming in pursuit of one’s nature. Endeavouring to demolish the prison walls surrounding an individual becomes no less important than the work of demolishing the prison walls surrounding a wider community.

Red Flag of the Pelvis & Exiled Bodies

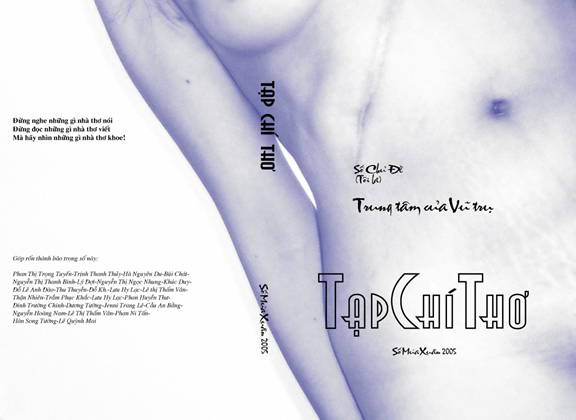

One point that sparked a feminist debate within the Vietnamese writing community in 2005 – regarding an incident of appropriation of the (female) body in writing – was a series of games following on from ideas the editors of Tạp Chí Thơ’s themed issue – ‘(I am) the Center of the Universe’ – concocted; exercises that asked the navels of 26 poets (male and female) to tell their poet’s story. This was done with freely written poems about the body, in conjunction with a ‘Guess Who’ quiz on the publication’s website (now deactivated), and operated as a game for readers to guess which poets ‘happily flaunt their navels to the world’ by clicking on those ‘navel-written’ poems. Other games included the use of body images, such as ‘Body Stall’, ‘Pelvic Gates’ and ‘Red Flag of the Pelvis’ o – each creating an animated party on the body and to provoke certain contrary reactions.

The most extreme reaction was that from a feminist group of female writers named Nguyễn Trần Khuyên (a combination of Nguyễn Vũ Khuyên and Trần Minh Quân) with an essay entitled ‘A Literature Constructed by the Masculine and Serving the Masculine’1. It presented two clear arguments: a criticism of the phallocentric works of male authors appearing in the online forums of Tiền Vệ and Talawas, and criticism of the female authors who participated in Tạp Chí Thơ’s games, asserting that their work was representation of ‘a literature serving masculinity – the lack of a feminist consciousness and culture in female writing’. Regarding phallocentricism, the group provided a critical statistic from their research, being that ‘images invoking sex and female body parts in order to express political and social views comprise around 70% of writing … Thus, one risk in the struggle for freedom and innovation is the direct insult of women by male authors who treat them as mere sex things, no more and no less.’ As for feminine acquiescence, the group contested that the act of female authors flaunting their navels as a manifestation of superficial feminist consciousness, was one trapped inside and reinforced the ‘tradition of phallicism.’ Subsequently, Nguyễn Trần Khuyên then initiated a petition to collect signatures in her Against Misogynist Literature campaign, demanding that Tạp Chí Thơ remove the abusive images that ‘expose the female body as packaged goods to satisfy male sexual instincts’2 from their website. Putting aside these sharply conflicting ideas among male and female writers, I found that this essay raised insightful points that could be further debated. It was a distinctly feminist voice – in conversation with previously initiated debates and ones that would follow, as with the female authors in Tạp Chí Thơ in the late 1990s, Tạp Chí Việt’s themed issue of ‘Love, Sexuality and Gender’, Tiền Vệ’s theme of ‘Love and Sexuality in Literature’, the criticism put forth by the Ngựa Trời group, themes of sexuality appearing in Da Màu and so on – which indicate the marked impact of sexual encounters on the overall literary landscape of this period.

Consider the compatibility of an idea put forth in ‘Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy’3 by Nancy Fraser. By identifying the idealised nature of the bourgeois public sphere and the blind spot of gender and masculinity in Jürgen Habermas’s conception of that public sphere, Fraser acknowledges the coexistence of competing public spheres of marginalised communities, including those that are excluded, and as exemplified in the women she categorises as ‘counterpublics’. The spontaneous feminist groups mentioned above represent one way to remain visible in Vietnam’s literary public spaces. I wonder, within reason, and in the pressurised political contexts of Vietnam’s human rights writ large, if there is a wider dispersal of individual voices on gender or race issues, such that they become weaker, possibly misinterpreted or pushed impossibly far aside?

Returning to works of female poets, we see the outbreak of narratives about / from the human body, and with themes of sexuality shaping experience and rediscovery of the exhibited self as a means of effectively awakening to – and thus confronting – the suppressing power of social bias. To a certain extent, the liberated body voice – emerging in both gleeful rediscoveries and in manifestations of pain – could be read as a textual strategy to attack popular Eastern patterns of beauty and femininity that often value silent suffering and the hidden. Making more or less grotesque aesthetic choices can disrupt the habitual use of decorative images of female beings and, necessarily, disrupt the enjoyment / consumption of female beauty according to the preferences of the male ‘customer’. How does it feel for women to expose a perceived taboo part of their body? Is it a joy to discover and master one’s own flesh? An embarrassment? Worth bearing a look of cold indifference? Or engaging the feeling of a struggling warrior? Lê Thị Thấm Vân has displayed the little hairs of her armpit in a playful way with a photo of her body:

Raise your hands if Thank you to the poet Đỗ Kh I have (had to) raise my hand to ask please may I to say here to agree to surrender to express a view among so many other whys. Now I (am) lying down raising my hand to proclaim the little hairs as newly sprouted from my armpit, that’s all.

Five female poets of the Ngựa Trời group appear on the cover of the Dự báo phi thời tiết poetry anthology, intended to be visually shocking and one of the reasons that the Vietnamese cultural censorship office issued a ban on the book’s circulation after its release.

- Archived in Talawas (2005, Vietnamese only) ↩

- Information archived on Gió website. ↩

- Fraser, Nancy (1990), Rethinking the Public Sphere: A contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy, Social Text (Duke University Press) JSTOR 466240, reprinted in Calhoun ed. (1992) Habermas, and the Public Sphere, Cambridge Mass: MIT press, pages 109–142. ↩