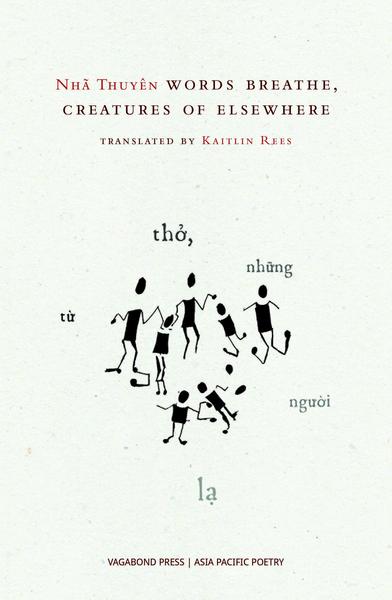

words breathe, creatures of elsewhere by Nhã Thuyên

Translated by Kaitlin Rees

Vagabond Press, 2016

The relation of place to identity and self-making is central to much poetry, indeed to writing more generally. It won’t be lost on the reader, therefore, that Nhã Thuyên, writing from Hanoi (‘river within / inside’) – a city built on lowlands; a city of lakes situated in the Red River delta, where rainfall is high – makes an impassioned plea for poetry (and thinking) that is fluid, unbounded, borderless.

In this, the author’s second full-length book of poetry and her first in English translation, Nhã Thuyên cautions that ‘ideologies can unconsciously lie in the life of our languages, and wish to frame us in narrow windows’ (12). A safeguard this poet proposes is the possibility of eschewing tradition, even form:

… poetry’s Vietnamese is where readers and writers strive to not give themselves over naively to the frames, to endlessly question those frames, with the possibility to leave them and not belong to them (12)

That said, the book elaborates rather than relinquishes structure. The prologue, ‘that intimate corner,’ accommodates five subheadings in a mere six pages. The body of the collection – just short of one hundred pages – encompasses a further five sections: ‘traces,’ ‘apparitions,’ ‘fire,’ ‘ash,’ ‘necromancy,’ and ‘words breathe, creatures of elsewhere.’ The number of poems in each section varies, from just a few in ‘ash,’ to a maximum of eighteen. Curiously, the contents page only contains poem-titles for three sections – absent are nine poem-titles from the ‘necromancy’ section and a further 18 poem-titles from ‘words breathe, creatures of elsewhere.’ The omission belies the extent of the collection’s aesthetic framework.

The poems, for their part, do articulate a desire to be unbounded and elusive, by gesturing toward that which might be said, or not; implied, or imagined. The language is frequently playful; its rhythms – marked by circling and questioning – exploratory. Nevertheless most poems utilise the entire line, and seldom abandon their prose poem form.

Early in the collection, the poetry presents as an exercise in free association writing. Journal jottings are indeed suggested by the dates in the right hand bottom corner of 12 poems. These textual features disappear halfway through the collection, at the section ‘necromancy’ – a turning point, for here the book’s earlier preoccupations are revisited but reinvigorated with a more assured tone. The body of the work, while still introspective, anchors more readily to the world through resonant imagery.

A stylistic feature of the collection is the accumulation of words and images. The impact of this varies. When disparate words create an amalgam the effect tends to be abstruse. Several similar in a row consolidate: ‘we were saturated in night smell, traffic smell, street smell, silent absence smell, in which i, nearly suffocated’ (39). In other examples, such as that below, words amass in a mushrooming formation; the effect of this hoard is dilatory:

at a corner of a wall stained sick fingernail yellow, we sat breathing in time, a tied breath, a calm breath, a sneering breath, a peaceful breath, a tingling breath, a hollow breath, a deserted breath, a euphoric breath, a penitent breath, an innocent breath (36)

In extended sequences, words and phrases cascade, gathering momentum, resulting in prose poems that are discursive, yet not lacking in poetic quality.

... puncutation marks exile themselves, a couple of scrappy words lounge around, a game draws to an end, a music is silenced, and edge of the abyss is thick with reeds, a sun rises, a bird flies from a bush, a wind fiercely blows at a precipice, the sound of your distant laughter ceased to make me wince, bit by bit letting each other go, not a single trace can be kept, not a single moment can be remembered, nothing can be carried, no-one can be called, nothing more of the early mornings, the noons, the twilights, the late nights of wild thirst for the moon, a panicked psychological disorder, an overwrought fever demands solace, this love will burn itself to death (97)

Discursive poems preoccupy the tail end of the collection; there are 18 in all: ‘discourse on distance,’ ‘discourse on reminiscence,’ ‘discourse on possibilities,’ on a storm, on a game, on water, on grass, on fire, on dreams, on a miracle, on light, on an explosion, on the call of the herd, on the body, on choice, on parting, on the loser, on the denouements – one after the other like a row of hurdles. Surprisingly, though a reader might anticipate a dull inventory, these prose poems are buoyant, in the main, and rich with sensual imagery.

Ironically, despite the intention to eschew form and keep meaning intangible, the recurrence of words throughout this collection proposes a narrative: Love – in so many metaphors. Love is a journey, a fire, a plant, the result of natural forces, unity, and exchange. To cognitive linguists, such metaphors demonstrate the conceptual systems underlying language, frameworks no less. Even the loss of love and its concomitant narrative of suffering – craving, lost attachment, anxiety, incompleteness, all that is unsatisfactory when love is unsatisfactory – is thrust into ontological correspondence. The biographical border of subject / lover is thus foremost of concerns.

‘an infinite ending’ is the translator’s response to the work and to the act of translation. These parting words provide an exegetical lead out of the collection – though with the promise of a continuing conversation.

That conversation seems likely, given the affinity between Nhã Thuyên and translator, Kaitlin Rees. Their collaboration for this collection achieves appreciable synergy.