Diurnal by Jane Joritz-Nakagawa

Grey Book Press, 2015

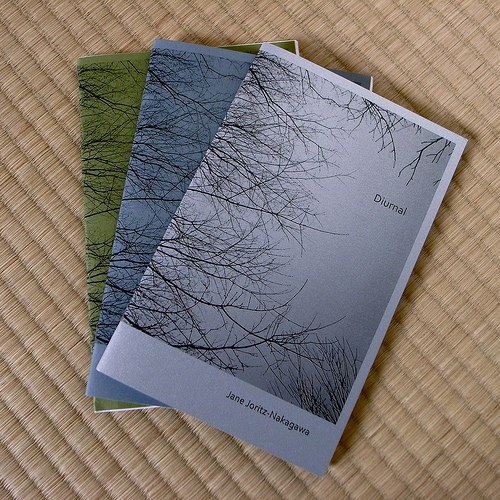

Jane Joritz-Nakagawa’s Diurnal is a slim chapbook of 24 numbered poems of seven two-line stanzas, which by my reckoning makes it a sonnet sequence. The cover of the edition I received is reminiscent of silver gelatin, with stark tree branches visible in the glooming (the chapbook comes in a series of three colours). The image is evocative of the tone of the poetry and while the title evokes the daily, it suggests that there are long, dark days of the soul, as well as nights. What of the noir of the day?

The sequence begins in media res, as if the reader is privy to a conversation addressed to a mother, lover or other; it’s never clear. The poetry seems underpinned by grief (there are recurring, fragmentary images of hospitalisation, illness, anatomy and death), though its focus is ultimately on a female lyric subject, or the ‘self’, at times speaking to the female grotesque: ‘womb crawling towards/a demonic mother’ (4).

It’s never clear who’s who. This from poem (2) may suggest a mother and daughter, though is the gown a hospital garment or a frock?

sleeve of abandonment dismembers the landscape silhouette gown stitched in space choreographed my childhood while averting my tongue purging the sublime blur or whatever buffet of disease sorts the garbage

The final two lines are emblematic of the kind of abjection that haunts this collection, in the Kristevian sense of the horror of things mingling beyond distinct catagorisation. As the speaker announces in the following poem:

i must continually throw up the see-through daffodils (3)

The interruption of directly denotative meaning is a linguistic strategy familiar to experimental poetics and there’s a meta-poetic at play throughout this collection – ‘a hex of language’ (11). It’s a long, virulent torrent of a sequence, yet when broken down into words it might have been written on flashcards or in hallucinatory fridge magnets.

Originally from the USA, Joritz-Nakagowa has lived in Japan since 1989 and the collection is peppered with Japanese images: ‘crowded train/empty shrine’ (18) and in the following poem a ‘monetized tree’ (19). There are also various more global references, creating ‘questionable bridges between worlds’ (6) such as ‘cowgirls with misshapen tails’ (6) and ‘bullets in shopping malls’ (9). While the external world (both natural and cultural) is part of Joritz-Nakagawa’s fleeting mélange, it often becomes a metaphor for interior landscapes:

a fine mist becomes despair in cautionary hypotheses (6)

And again, in the following poem, where a ‘panic of thoughtless trees/lurks inside’ (7). The break-down of distinctions between the inside and the outside of the body gives the collection a sense of flickering transparency, like an x-ray or avant-garde biopic:

strange machine drooling memory winding column overblown selfie (16)

The restrained precision of the sequence’s structure makes the language at once automated, and yet visceral and embodied. Dis-ease is at the heart of the poetry and this is a book of desolate aesthetics and daily repetitions, like ‘sweeping the sidewalk endlessly’ (23). At one point I thought that this collection might span a single day, but it is more likely a much vaster time period, a ‘system of time/with hollow doors’ (24).

This is a very seasonal book, a book of Winter, that I read with a hot pot of chai tea overlooking a stormy Pacific Ocean. I’m currently in the middle of writing my own sonnet sequence, set in Newcastle, and felt something of a kindred conversation from across the sea – ‘extremely aware of women / trajectories of bleak pull’ (4). If the traditional sonnet was built around the volta, contemporary sonnets such as these become almost all ‘swerve’, and the fractured meanings multiply within multiple contexts: the line, the stanza, the poem, the sequence and out into the world beyond. In (12) the idea of the self as an imposter, ‘je suis charlatan,’ is perhaps a desultory echo to the rallying cry for freedom of self-expression encapsulated by ‘je suis Charlie.’ Given Joritz-Nakogawa’s association with eco-poetics, the final two lines of the collections seem to gesture to the human and the non-human, and provide a fittingly succinct point of exit after the preceding disquiet.

drama of the street

empty hills, no one in sight (24)