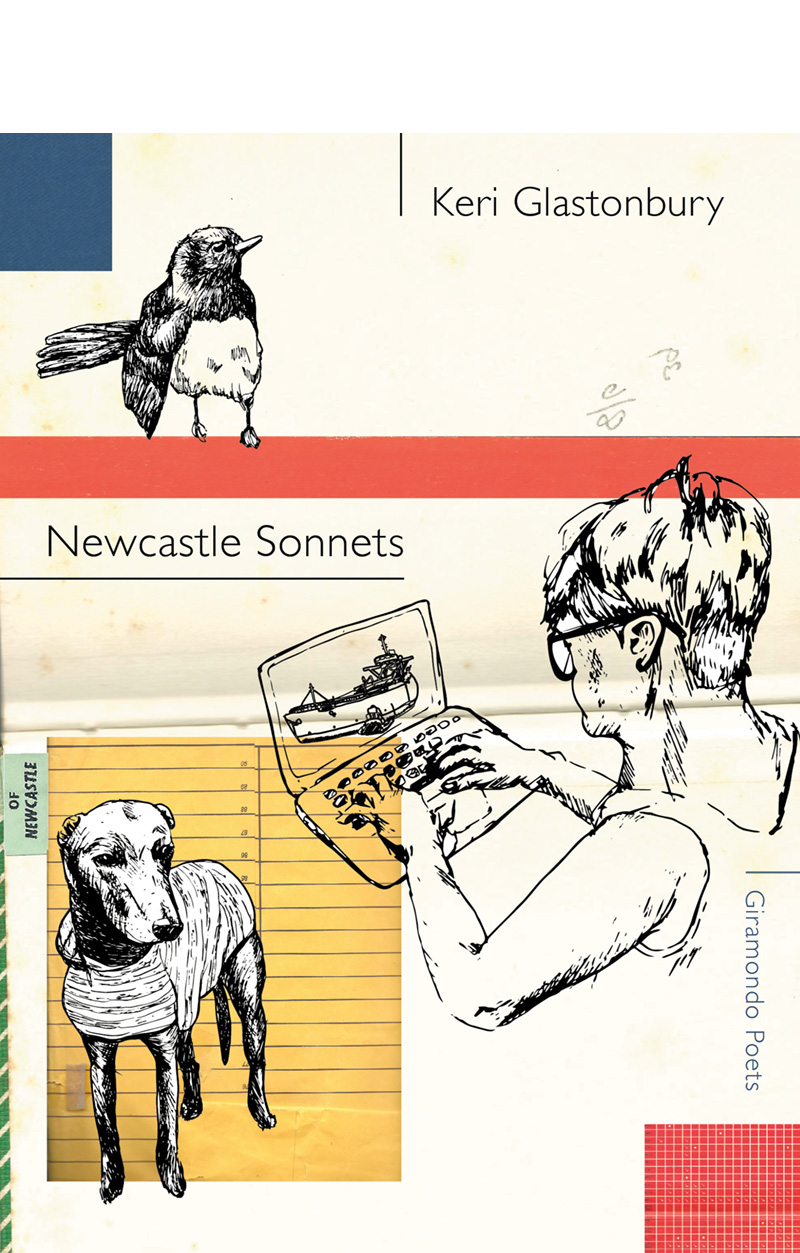

Newcastle Sonnets by Keri Glastonbury

Giramondo Publishing, 2018

What is it about the sonnet? How is it that the infinite possibilities of those 14 lines can remain as persuasive and perplexing in 2018, in Newcastle, as they did in fourteenth century Italy? The persistence of the sonnet – the fact that we continue to return to, remodel, and mess with the form – is part of its charm. On one level this speaks to the sonnet’s original function – to express desire, a desire that lusts not only for the other, but for the poem. In writing a sonnet, the poet exercises the will of the troubadour, that is to demonstrate one’s ability as a singer. The purpose of the sonnet then is not only to woo the beloved, but to woo poetry itself. For Keri Glastonbury this return to form, this return to court to prove one’s spunk, is designed to ask a question hanging over the crisis of late capitalism – where did our court go?

Like the spunks before her, in Newcastle Sonnets Glastonbury pursues this desire to make new, to do things better, to speak back to, and to reach further. However, this ‘making new’ is perhaps less interested in what the end product looks like and more interested in the process of this making, specifically as it relates to the construction of self and place within the post-digital. In traditional, formal terms these are sonnets in as much as they contain 14 lines and because Glastonbury tells us they are, but there’s no rhyme scheme or metrical measure. Rather, these sonnets speak specifically to the New York School (most persistently to Ted Berrigan and Frank O’Hara), and those poets who reshaped the form, struck out against its rules in order to redefine what desire looked like. The collection opens with an extract from Ted Berrigan’s ‘Personal Poem #9’:

I think I was thinking when I was ahead I’d be somewhere like Perry street erudite dazzling slim and badly loved

These lines astutely capture the kind of desire that drives Newcastle Sonnets; in this collection we find a desire for the other, for the self, and for place, but most importantly we find a willingness to dwell in the uncertainty of that desire (‘I think I was thinking’). Notably, this is an uncertainty that is characteristic of the self-conscious new-confessionalism established largely by the internet.

‘In Newcastle, in Tokyo …’, the collection’s opening poem, is in the grip of this uncertainty and offers a mapping of its process. It positions Newcastle, a city still in the beginnings of its technological expansion, still entering and absorbing modernity, in relation to Tokyo, the ultra-modern techno-hell/heaven (depending on what angle the light hits), the metropolis that has by now toppled over its own peak. There is the desire to be elsewhere and among the expanded world, as well as a nostalgia for a younger and more naïve self.

who knew when I read those sonnets in the library, that I’d later be penning them from an office in a world-class ‘gumtree’ university?

We also have Newcastle as it desires its own past lives, or, more importantly, the way in which this nostalgia is produced as capital: ‘a local shop / sells pannikins & Mason jars, the post-industrial / as an in situ conceit.’ There is the humorous quip of ‘Oh public transport envy!’ which signals a desire not only for Japan, but also for great poetry (the line being a reference to O’Hara’s ‘Meditations in an Emergency’).

There is the desire for immortality, or at least the desire for a long (but mostly importantly remembered) life, notable here in a reference to Misao Okawa, who was for a period the world’s oldest living person (and remembered because of this). Again, this is a desire that is placed in direct relation to the past as capital, a dialectic that Glastonbury presents throughout the book, reaching as far back as the stone age: ‘There’s a Misao Okawa / in us all, drinking paleo hot chocolates / the way our ancestors made them.’

In the end the speaker doesn’t get what she ultimately desires, ‘but there are small advances’. What we get instead is a willingness to exist somewhere between having and not having, an uncertain space, but a space that makes room for valuable and cutting critique. Glastonbury is willing to pause in process; these are poems that show us a willingness to exist in the ‘ums’, an ‘um’ that is both discerning (um, are you serious?), and unsure (um as stutter).