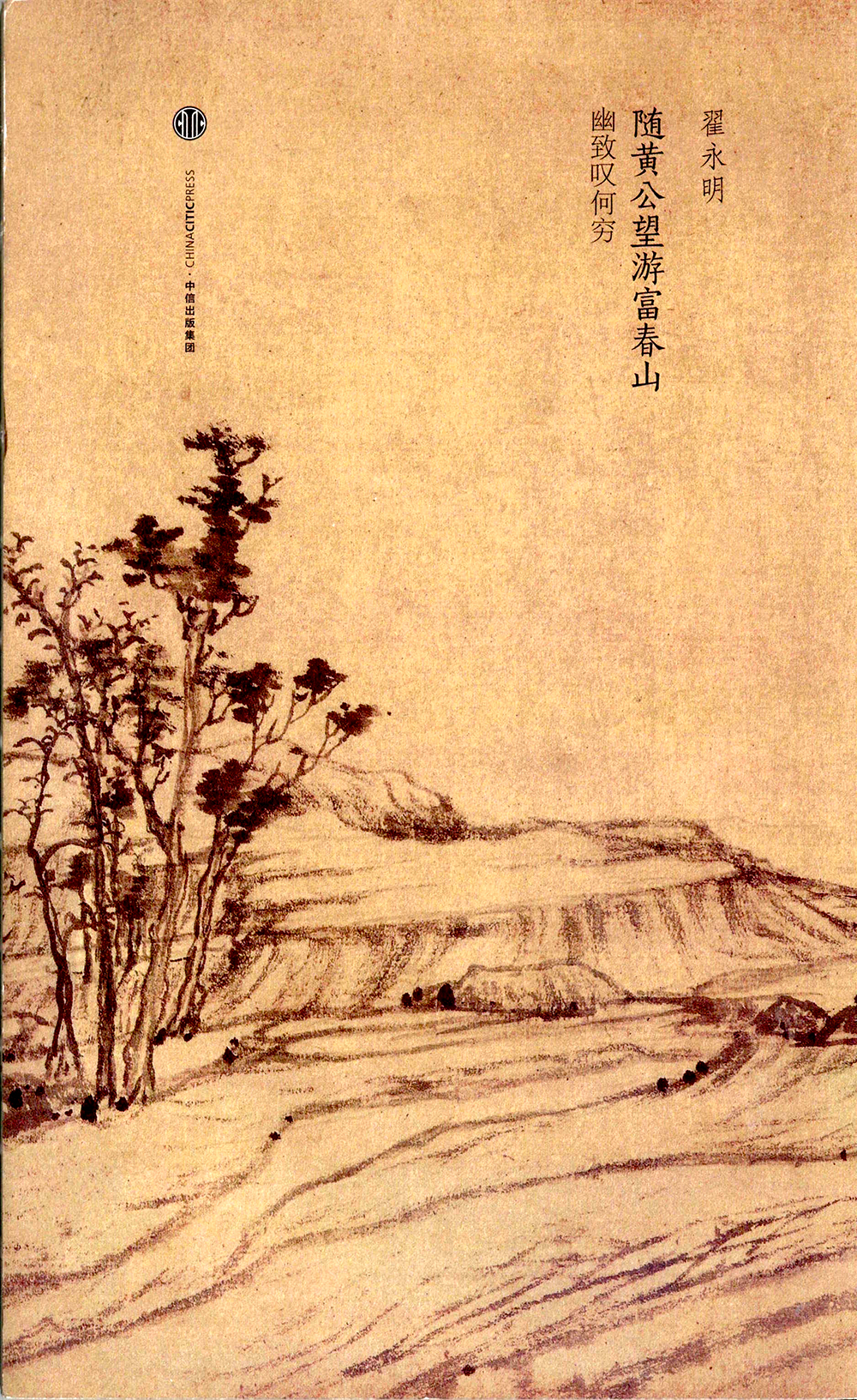

Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains is a handscroll by the Taoist painter Huang Gongwang from the Yuan Dynasty. It is now acclaimed as one of the ten masterpieces of Chinese painting. Inspired by Huang’s work, the renowned Chinese poet Zhai Yongming published her latest collection Ambling along the Fuchun Mountains with Huang Gongwang in 2015. Chen Si’an, a young theatre director and novelist, read an earlier version of the text and was inspired to create a theatrical adaptation. Sharing the title of Zhai’s poem, Chen’s play premiered in Beijing in 2014. This essay explores the life and after-lives of Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains.

The Painter (1269–1354)

When he was still a boy, the painter sat for the imperial examination for child prodigies. We don’t know whether he passed the test or not – his biographer doesn’t say – and, in fact, none of the biographers seem to agree with each other on the painter’s birth place. Some even find his family name, whether it’s Huang or Lu, disputable. He called himself many names. Gongwang 公望 and Zijiu 子久, the former given when he was born and the latter adopted when he received his cap, a symbolic gesture for reaching adulthood. Other names including Da Chi 大痴 ‘the biggest fool’, Da Chi Daoren 大痴道人 ‘the most foolish Taoist’ and Yi Feng 一峰 ‘one peak’, probably taken up when he embraced the Quanzhen School of Taoism after being persecuted for his involvement in a corruption case. Disillusioned but not disheartened, the painter joined the tradition of dejected literati who withdrew from society to live in nature. He retired to the mountains along the banks of Fuchun Jiang 富春江, the river of luscious springs.

He didn’t take up painting until he turned fifty, and that might be why the landscape in Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains was so unhurriedly spread. The opposite of action painting in the sense that there’s no sudden explosion in front of your eyes. Everything falls into place and stays, except the blankness left intentionally by the painter at the top and the bottom of the scroll resembling moving clouds and waters. He wrote in his Secrets of Landscape Painting that ‘a painting is nothing but an idea’. On the creaseless water near the mountain, a fisherman sits on a raft, bending towards an idea. An idea is a living thing that pulls your fishing rod from under the water.

The Collector (1650)

Paintings are dwellings. A seven-meter-long handscroll is even more inhabitable. Some say that the last collector of Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains became so obsessed that he kept the handscroll close to him even when he was having tea. When the Manchurians came, he fled with only two items from his extensive art collection, one was The Thousand Character Classic written by the Sui monk Zhiyong 智永 in the calligraphic styles of Zhen 真 ‘regular script’ and Cao 草 ‘cursive or grass script’. The other was Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains.

The more the collector dwelled upon the handscroll the more possessive he became. On his deathbed, he ordered his family to set it on fire, and they did. Except one of his nephews suddenly grabbed the burning scroll, lifted it out of the flames, and quickly chucked another scroll in the fire without being noticed. Paintings are dwellings that can easily be destroyed by fire. The scroll broke in half with a great section burned to ashes. Now the beginning half referred to as ‘Remaining Mountains’ 剩山圖 is kept in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Mainland China. The second, longer half, now known as ‘the Master of Uselessness Scroll’ 無用師卷, is preserved in the National Palace Museum of Taiwan.