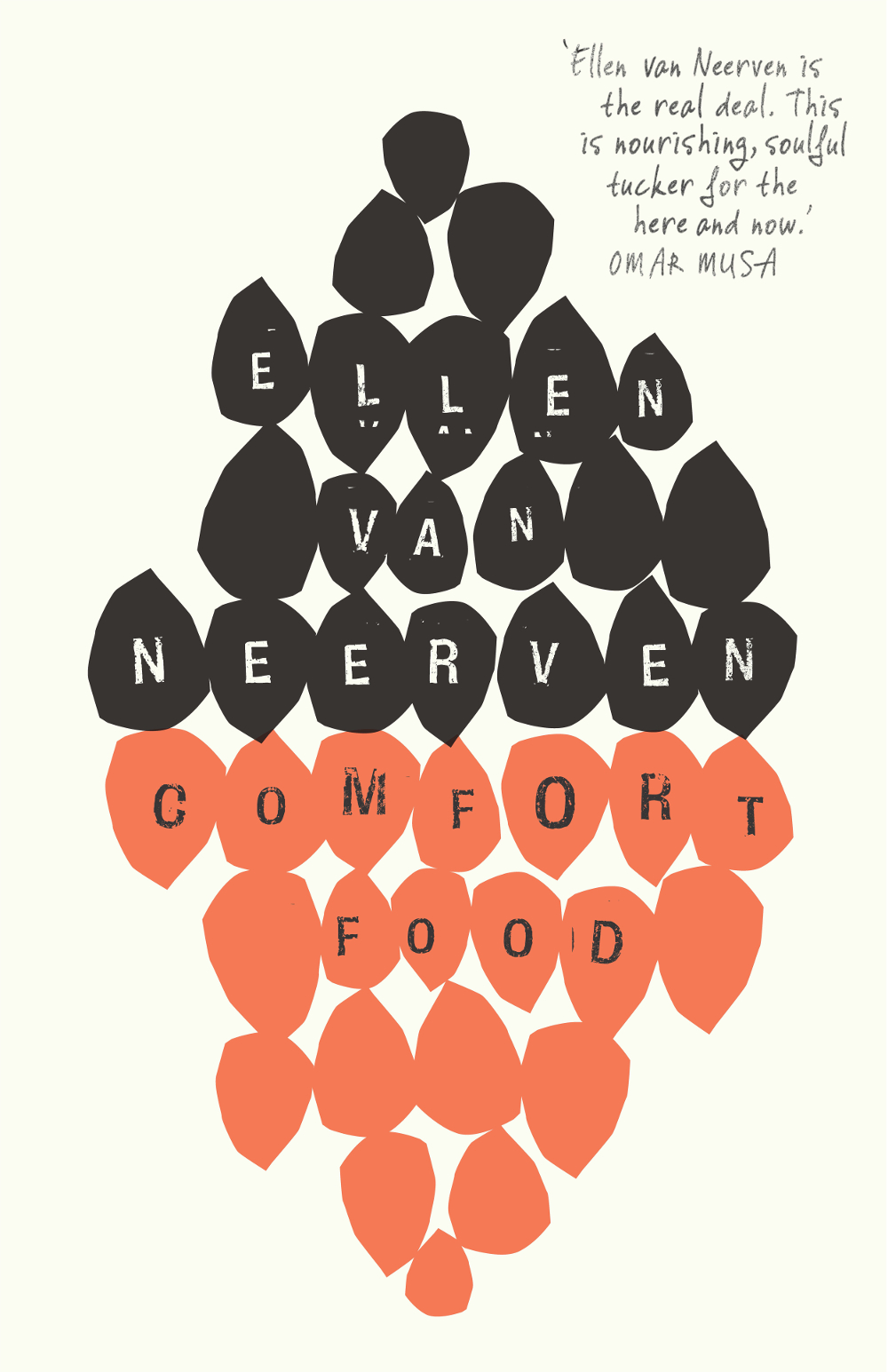

the leaves are my sisters by Jill Jones

Little Windows, 2016

that knocking by Andy Jackson

Little Windows, 2016

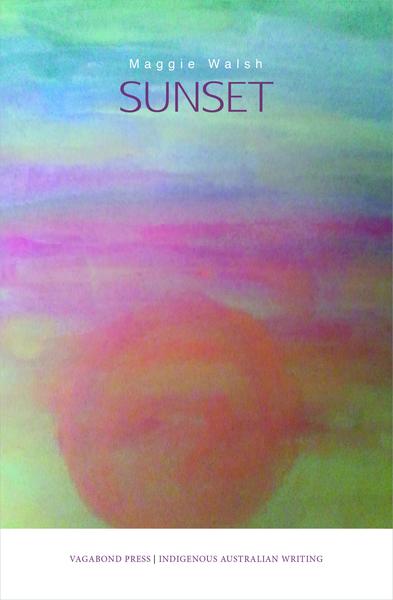

semiosphere by Alison Flett

Little Windows, 2016

empire of lights by John Glenday

Little Windows, 2016

Reading Jill Jones’s poetry I am struck by its skilful take on classicism: Greek for its entangled beauty, immortality and power; Roman for its urbane wit, its insouciant dealings with discourse and desire. For example, her poem, ‘they are about love’ recalls rapid Sapphic shifts: ‘Today begins colder, amid magpie scurf, bird mind’. In ‘the end of may’, the speaker’s colloquial quip echoes Ovidian word play:

Then the bloke in the truck

gets down and has words with another bloke.

I have words too, checking them on pages

as if getting past each line or sentence is something

achieved, or, that’s right, important.

These poems appear in Jones’ 2016 chapbook, the leaves are my sisters, one of four that form Little Windows 1 (LW1), an impeccably presented first series from Adelaide-based Little Windows Press. The rationale for Little Windows is to provide the reader ‘a “little window” into the oeuvre of each poet,’ pairing two Australians with two international poets. The line-up of this inaugural series features Andy Jackson (Victoria), John Glenday (Scotland), and Alison Flett (South Australia, via Scotland), alongside Jones.

The full set of LW1 arrives in the post like a present, a gift-wrapped bundle of square, slate-coloured books. It came to me looking so perfect, that a couple of days passed before I had the heart to a prise a chapbook from under the clear binding ribbon. This situation gave shape to a thought about the necessity of obstruction in order for words to seduce. Some form of this theory of desire continued to occur to me as I read the books’ divergent visions. ‘Little window’ is a deceptively modest turn of phrase. The idea of a window is flashy, slippery, multiple. It lets light in; it frames a view; yet it also obstructs. To compose this view, it selects and rejects by contingency, including and excluding what may be shown. It might be thought of as a technology of presencing – a way of making a present moment visible. At the same time, there is a wishfulness about windows, which frame an ‘out there’ inexorably out of reach to the viewer: once entered, the view of the window disappears.

Poetry shares these frustrations of representation: in the poem, discourse and the object of desire can only nearly coincide. That the representations made by the poem cannot but mediate and obstruct reality is the basis of the perversion necessary to the production of poetry itself. Jones’s ‘having’ of words, ‘as if getting past each line or sentence is something / achieved,’ alerts us to a fundamental fetish of poetry. Her seeking of the productive stimulus for the writing of poetry echoes Ovid’s Amores, whose speaker demands the existence of obstacles in order that the lover-poet may be always thwarted, and thus be given the opportunity to deceive, outwit, seduce (in other words, to use words). These three terms are translated from Ovid’s original verba darem, which literally means ‘I give words.’

In the final stanza of Jones’ ‘the end of may’, the speaker catalogues:

That the leaves are also shining today.

That there’s still a golden sense in greying stonework

of the early twentieth century building

in one corner of the courtyard.

That there’s still dust on the plate glass windows opposite

and they never seem to change in any light.

That birds in all this time will sing longer than

the courtyard and the desk, the buildings and the squares.

That this doesn’t matter, that it does.

The coy equivocation in the final line highlights that the more the speaker talks (‘I have words too’), the less is achieved. Jones’ giving of words eroticises a world at once close and remote, caught in present-tense nostalgia: greying stonework is ‘golden’, the light on the dust unchanging. Nothing happens, and there is everything to say about it – the profusion of beautiful lines affirms logophilia as a brilliant perversion through which to try, and fail to touch the world.

With an authorial intensity to match Jones, Andy Jackson’s that knocking delivers the most knockout opening of a poem I’ve read this year:

you are disabled

whether you admit it or not

did you know that? (‘unfinished’)

The muscular use of the second person is arresting, stunning. Staccato lines crack, cajole and wound the textual body back into the physical: ‘can’t speak / your mind without your body // being twisted into some other / locked-in meaning.’. Poetry of such a brutal order might nearly be up to facing the ‘truth’:

but don’t get carried

away – your failure is not

at all the same as mine

each map of scars

leads back to the world

no words can hold

what has been done to us

Like Jones, Jackson boldly addresses the failure of words to signify, work, make happen, or ‘hold/ what has been done.’ But only by means of the ironic proliferation of words against failure – broken, breathless, twisted lines – could such a point be expressed. The relationship between the speaker and the addressed anatomised body brings to mind the disturbed, yet unpredictably empathic vision of Patrick White’s artist in The Vivisector. By comparison, Jackson’s that knocking’s abstract renderings of Australian spaces might also be seen to chime with White’s oeuvre. In ‘blue mountains line’, body and machine collide at high velocity: ‘the carriage is the colour / of tendon and bone.’ Familiar landscapes glide by in a green menace, drawing violence and tenderness by equal measure into the poem. The poem wobbles and knocks – and openly fails to signify – with the motion of the train. As the speaker of ‘circling home’ says, ‘the ways me miss our lives / are life’: cynicism is discarded at the outset, giving way to bittersweet fragments of life-debris.

Alison Flett’s semiosphere follows a similar principal to yield, in this case to a post- (or para-) anthropocentric world populated by foxes. Flett’s book is structured around a series of deft, elegant perspectival shifts, charting a sequence of experiences that oscillate between encounter and symbiosis. Language is playfully de-civilised, perhaps with the intention for rehabilitation to the wild. The opening ‘votives’ is a graceful prose poem of long, solemn lines, with a final stanza that invites the reader to:

Look deeper into the forest’s dark heart and you’ll see the tapetum lucidem

of many creatures looking back, amongst them one who has been waiting there

for you.

The following poem, ‘fox 1: umvelt’, immediately surprises with its short stanzas stepping across the turned page. The lines have diffused and spread out, like a pack of wild animals on the run, their wildness hiding in the city’s plain sight:

I have seen a fox move

in silence through the city

and this I know

the trees breathe the fox

and the wet black pavements

shine for him

‘fox 2: corporeal’ shadows this stylistic direction, the stanzas’ typographical separation emphasised by their thematic organisation according to synecdoche (eyes, tail, heart, feet). But another wild shift arrives in ‘fox 3: liminoid’, thick with hectic prose. The run-on lines perform the panting, unpunctuated swagger of partying twenty-somethings loose on a wild city night of their own:

with the music of the club still beating in our blood and the thought of the

party pumping in our veins and the freedom of walking along the middle of the

road because it was early morning and there wasn’t any traffic yet and it was one

of the streets that if it had been daylight

The speaker is the only member of the group to see a fox crossing the road, and a hitherto quotidian memory gives way to another order of experience, belonging to an ungraspable, deep ecological memory. Can such a deep memory survive its retrieval by words? Through its insistent animal presences, semiosphere speaks of a world haunted by speechless living. Flett’s tightly structured, experimental text is impressive beyond her facility for stylistic variety. Woven through her tropes of encounter is the question: how can humans remember they are animals? And subsequently: can language be made to speak this fact? Can language be wild?