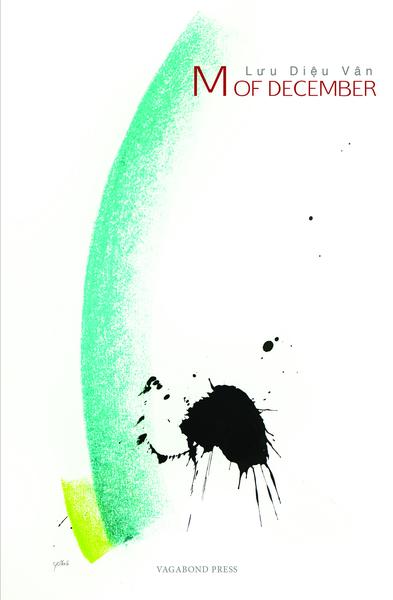

M of December by Lưu Diệu Vân

Vagabond Press, 2016

Reading M of December is rather like going to a spectacular exhibition at a gallery where images of all kind swirl, proclaim, collide and re-form – the viewer takes the opportunity of a brief leave to attempt to come up with a coherent response. Having gone into this gallery, and exited on a number of occasions, what I have come up with is a response to the formed fragmentation of its individual poems, travelling through discordancy via the robust vigour of forceful lines and sharp elisions.

In the first section of the collection, ‘December’, individual poems read as constructed assemblages with dazzling juxtapositions of imagery. In ‘B.C. bees’, perception is presented as molten, contested, as chthonically and chronologically unsettled:

the fire has eyes that glide through lies beyond B.C. and cunning centuries the sage offers secrets to the universe seeing is a plague the distance between heaven and death is a U turn

The artist at work then makes a selection process by constructing a verbal installation:

each century’s special promotion written in the DNA of people making headlines the telling bees dash for the wedlocked bedrock like thumbtacks on a topsoil cork board sucking out stories as big as Vesuvius’ pumice mortality preserves in conceding hives

This sense of poem as installation, or constructed artefact, is also on display in ‘micro exhibition’, where images of the artefact and that of the natural world play off each other, reflecting both boldness and uncertainty – wonderment in the faith of what the poet has created. The poem starts out with a strong image:

a religious artefact stands imposingly, sanctimoniously reflecting the recondite sea beneath

The imposing nature of the image could be seen to conflate into the act of perception itself:

the glass incrustation patiently collects black and white stones of uncertainty, downplays the six senses, magnifies the perception

This culminates in the final verse, where the act of writing itself presents ambivalently:

on top of the mountain lays a hesitating temple of ink, half wanting to leap, half keeping hold of subsistence

Essentially, Vân works herself out of hesitation; boldly placing the natural and the constructed to achieve a momentary interlocking of effect.

In ‘imaginary holy friend’, the robust somehow distils itself into an evocation of lyric, socially sanctioned violence. Here, the gendered de-formations of ‘people playing god’ merge into a joint reflection of the abused body and nature, with the short lines being particularly effec-tive:

god frolicking people elongated neck binding people playing god moon-blade foot binding slippers stumped by lotus ponds punctured meat of the bony flute meshes pain filtered cries hair side-parted slope of decisiveness gossamer crease hidden in plain terrain mountain goiter of the soil lake urethra of the deep volcano mouth of the inflamed smoke lung of the unsung a favourite blacksmith of mortal parts to play Operation with in the bedridden darkness

The poem ‘inside an armoured chrysalis’ pursues the vision of metaphysical clash in its expressionistic and apocalyptic tableau of war:

the cloak of war rips open like a caterpillar’s final grip on innocence seas of poppies barrage from rising towers

Its imagery is strong and confrontational, for instance: ‘stench of fresh fir’, ‘molecules of gassed up bodies’ and ‘thinning polyskies of barebones and sulking skulls’. The delicacy (and the shorter line) seen in ‘imaginary holy friend’ effectively returns in the final two lines, playing out the metamorphic import of ‘chrysalis and caterpillar’:

the rest of us frantically disperse in search of a butterfly that can cry

The section, ‘December’, continues with an enthralling juxtaposition of imagery from nature, the world of objects, and the body, all morphing into each other in unexpected combinations. ‘coiling forest’ presents a take on the Cinderella story, of ‘tales of a princess always needing rescues / of a prince.’ Vân portrays a set in motion, in which ‘a vanishing forest [is] coiling into itself’ and ‘doors are pushing upwardly silently within the forest like wild / mushrooms.’ The poet abruptly segues from this protean vision, into savage reflection:

Cinderella never made it that last second of the forest’s final new year’s eve when no one can own sadness but merely takes care of it for the next victim in line

In a similar vein, ‘melancholia of caramel afternoons’ moves from the mythical to the contemporary with spectacular elision:

nirvana the night’s cologne caging in missing hinges from its macho wings on the wall of memory Sabrina arrives through the urgent ringtone

The second section of the collection, ‘M’ is akin to work seen in Poems of Lưu Diệu Vân, Lưu Mêlan & Nhã Thuyên (Vagabond Press, 2013), extending Vân’s poetry both in theme and imagery, nailing the acerbic line. ‘to a younger poet self’ and ‘naïve writer’ respectively look back in sardonic reappraisal: of, firstly, an early love affair; and, secondly, of early flurries onto the literary circuit. In ‘to a younger poet self’, the ‘Big Heartbreak’ is framed with literary reference:

all your twenty-two self-pities a fatal infatuation for Rumi and e.e.cummings insomnias yet of age jolts of maiden pain love smog tints grays of verses laments vicariously postaged to Neruda

Its references morph into an effectively crafted take on writing and the body:

you shatter into creation the feminist phoenix way riding in the dark on the biro’s horn rendering poisoned sensations savable chastity’s optional to tame metaphors you jump through a needle’s eye avoiding the thread’s pull

‘naïve writer’ also sees the collection open itself up to some narrative savagery. In Vân’s view, literary PR appears as the selling of self, where ‘the writer’s skin must be as thick as their copious flows of / topless appearance on the fictional bed’, this ‘literary reception / bed, on which not a single space is deserted’, from which the speaker is suddenly excluded, ‘forever trapped outside’.