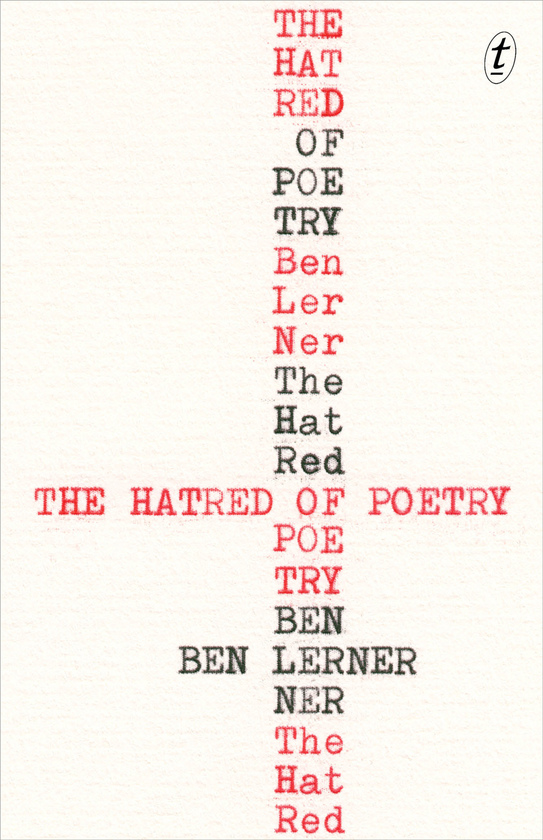

The Hatred of Poetry by Ben Lerner

Text Publishing, 2016

Reflecting Ben Lerner’s considerable reputation as a novelist and poet, this essay speaks in a voice both sure and self-deprecating. At this level it has already fulfilled a conventional definition of its genre – the effort of rhetoric to explore an idea or problem. The problem that Lerner considers – why is poetry a subject of hatred? – is hardly urgent, and he is quick to admit this. After all, the essay’s topic is an inverted defence of poetry, a tradition with a long history. The pleasures of this contribution, therefore, are Lerner’s unashamed and confident belief in poetic form, and the sympathetic truth to be found in his conclusions.

The ebook of Lerner’s essay presents a narrow, condensed column of text, which we could see as a nod to enjambment (visually, not rhythmically – this isn’t a lyric essay). The margins in the print version, while still generous, are less of a feature. Nevertheless, in both formats this padding (the Projectivist field) feature paraphrasings of the body text, a bit like pull quotes, little echoes or a chorus (and sometimes hecklers) of resonant metaphors. As an extension of its content, this essay’s form is a reminder of the author’s own poetic craft, and a simple but pointed interruption of the familiar prose paragraph.

What is expected of poetry, and what should be expected? Lerner’s discussion revolves upon the sentiment found in Marianne Moore’s ‘Poetry’, specifically, that to read poetry with honest contempt it is to uncover its workings – and its alchemy. Using Moore’s insight, Lerner insists that the hatred of poetry is necessary in order to read and write against the poor examples and traps of the form. That is, to hate poetry is to understand ‘the gap between the actual and the virtual’ which constitutes the poetic treatment of language. As Charles Bernstein asserts in his defence, ‘The Difficult Poem’, ‘a poem may be easy because it is not saying anything.’ The hatred of poetry is to see the failure of poetry, and that is a good place to begin loving it.

In examining this ‘gap’ or failure, Lerner sets ‘the abstract potential of the medium’ against language that does not call itself poetry. We might compare that abstract potential to the way that paint, clay, fibreglass, the body or the voice are used in other art forms. It is often most starkly visible in works that draw attention to their re-contextualisation of the medium, such as Marcel Duchamp’s readymades or Kenneth Goldsmith’s uncreative writing. Perhaps what distinguishes poetry from those other art forms is that human language occupies the thing we consider the least abstract of all – consciousness. Lerner does not address this distinction or condition of poetry, however – perhaps because it would require fattening the essay into fields of biology, speech act theory, art history and more, which would ruin the svelte line of that unbroken, inarguable column. His essay’s intense focus and economy are as much proof of the author’s poetic flair as its ideas.

It is important to point out that this essay, while agreeable to poets, is not an exclusive address to them. On an intuitive and observational level it is hard to disagree with his theory – surely Aristotle would not – that non-poets are fallen poets, that is, those who have ‘poetic capacity as all language users do, but who have let its art leave them.’ For Lerner this condition explains the mutual embarrassment caused when the adult poet announces their art: the poet wants to efface her backwardness, and the non-poet feels ashamed of his lost self. Here, Lerner treads soft anthropological territory: ‘The ghost of that romantic conjunction makes the falling away from poetry a falling away from the pure potentiality of being human.’ This seems to pick up on the closing stanza of Moore’s poem:

if you demand on the one hand,

the raw material of poetry in

all its rawness and

that which is on the other hand

genuine, you are interested in poetry.

It is a little difficult to reconcile this vision of the human condition – and when or where the fall occurs is not indicated by Lerner – with the narrow cultural scope of the essay’s textual examples. Lerner draws mostly upon modern, Anglophone poems, so we must assume that ‘poetry’ in this essay refers to the modern, Western tradition that calls it such. By extension he suggests that the hatred of poetry is a normal condition of Western readers. In this way Lerner limits the texts and readers to which his thesis may refer; a clever rhetorical manoeuvre, since a broader cultural or linguistic field of reference requires a scholarly depth and breadth that, once again, would turn this essay into a different creature altogether. Lerner embraces the essay for what it is allowed to be – a snake-hipped gambit – but in doing so he protects his discussion from its own gaps.

Lerner implies his awareness of this, when attempting to understand what a defence of poetry is about. It is, he says, an ideal way to write about what poetry is or should be without having to go through the actuality of struggling with a poem. In some ways the genre of the defence (and the manifesto, as he later argues) has worked counterproductively, by simply alluding to the qualities of poetry without forcing the reader to engage directly with them: ‘Which is not to say that defences never cite specific poems, but lines of poetry quoted in prose preserve the glimmer of the unreal.’

This cannot be said for William McGonagall’s ‘The Tay Bridge Disaster’, which Lerner analyses. In such an example, this gap between the poem’s virtual and actual success can be perceived by those with even the least interest in or knowledge of poetry. In a very bad poem like this one, the difference between intention and result is palpable:

we feel the immense ambition – the impossible ambition – internal to a poem like McGona gall’s, feel it all the more intensely because of the thoroughness with which his ambition outpaces his ability. A less bad poet would not make the distance between the virtual and the actual so palpable, so immediate. Nothing mediocre: The more abysmal the experience of the actual, the greater the implied heights of the virtual.

As Lerner is at pains to point out, the late critic Allen Grossman is a key critical source for this argument. In his essay, ‘The Poetics of Union in Whitman and Lincoln’, Grossman sets out what is to become the thesis underpinning Lerner’s essay, including Lerner’s own lengthy analyses of McGonagall and Walt Whitman. Grossman writes:

One reason we turn to criticism of poetry is to bring to pass projects that become possible only when we make statements about poetic texts … In this sense, we do not intend the poem; we intend the intention that brought the poet to poetry … Our judgement upon the poem is an assessment of the likelihood of the coming to pass of what is intended.

Grossman’s argument is that poetry tries to imagine its better, impossible self – the place where language is abstracted from structure and yet can be received like a telepathic bolt – a poem that leaves no footprint. So when Lerner arrives at the central conclusion of his essay, the chosen metaphor completes his extension of Grossman’s theory: ‘The hatred of poetry is internal to the art,’ writes Lerner, ‘because it is the task of the poet and poetry reader to use the heat of that hatred to burn the actual off the virtual like fog.’