With your languid pose, your elbow against a tree, your flute, and your costume cut into

diamond shapes.

Simultaneously for and against this tradition of minor failure, you have acquired a

cummerbund.

You said we have both a colony and a god.

Smudgy, thick, cold.

To spare myself I’m going to drop these you said.

So long big doors, painted with sea-light and honey.

To spare yourself the trouble you’ll explore beginner infinities.

So now you are an economist.

You meant that by remarkably indirect paths you’d understand one god simply in order

to let go of all belief.

So you came to nilling.

If life is your idea, it’s an idea with fur.

So you sent for some novels.

Sheet-lightening and large-dropped summer rain in short forays, 5am.

Socius rex.

Your misunderstanding stopped just short of thoroughness and this was your particular

charm.

Some believe you ought to assume a tone of sincerity.

It occurs in the smallest possible space.

Some have deep apartments, some have shallow apartments.

An idyll in a bungalow; a palpability; a loss.

Sometimes the concept of plenitude is a help.

A gate made of floral foam, beeswax, silver leaf, drywall.

Sometimes you need a record of your life.

How else do you construct a pause in cognition?

Speak, tiny expensive morning.

Grumblingly.

Still there was no solution for the fabulous problem.

With late style.

Still, at this late date in the political, you remain intrigued by fucking.

It’s time for your late style.

Still, you’re totally in love with subjectivity.

Mid-way along that line that marks the adjacency of description to perception you paused.

Such aesthetics are as unthinkable to you as they are necessary: memory and the present

are not in opposition.

You had more important things to do.

Such facts lie beneath the grasp of contemporary research.

At the edges of sensing, there is banality.

Such that flowers, skulls, tables, subvert the vanitas.

You craved the diurnal irregularities of the imagining life.

Supernatural, social and divine.

You sensed your future unfounding.

Tattered Europe caking up in corners of abandoned rooms.

Your goodness lifts like a cock.

Tell me if you haven’t had grief. Whatever grief is becoming.

You just adore its heavy beauty.

Tell me more about animals you said.

Free error is what you’d call it.

Temporary benevolent peripheries.

You burst to a skirty froth.

Was it enough?

You play and believe.

That love happened at all.

And so you hit upon your grandeur.

That morning in the hotel-bed, you experienced your thinking as moving surfaces that

intersected sequentially and at varying angles.

Then you lapsed in its observance.

That only your lovely arrogance permitted this.

You use speech to decorate duration for somebody. You stop just before it becomes a

shape.

That the snow prevented you.

Because it’s not a site, it’s a style and it hurts.

That they become their deaths you said.

Very easy and very desperate.

That year, all of your muscles became useful.

There you were, fucking gratefully near water because you could.

That your mouth lovingly damaged the language.

You went to the river just to gaze at the river, like an old man.

The act’s absurdity is balanced by its excess.

And you counted, you counted, you counted.

The balance changes, and you care less.

You almost thought.

The countess of prose in your abandoned orchard.

You said the market doesn’t merit belief.

The current place looks a lot like the world with its trees and houses, but, for example,

when you wake up, there is only one bird, and then that bird stops.

You wanted to make your tiredness into a surface.

The delicate coyote, the streetlights, the pungent night.

The houses you lived in, their porches, the bored women and girls working at the arena

snack bars.

The description takes over the inchoate category.

Where else can you think change?

The dry tree of your task, the citydogs cavorting.

You breathed for those who dedicated themselves to burning.

The feeling of your sex became more and more mysterious.

What’s the good of burning?

The form never extinguishes its own irony.

You are neutral, like an event.

The girl at the park fanning her hair in the sun.

Two doves in the pine; three, and a train; one gone and a dog in honeysuckle: how are you

to make choices when perceiving is arbitrary?

The grand law empties you of preference.

You moved the taxonomy around.

The houses you lived in, their porches, the bored women and girls working at the arena

snack bars.

Then you felt lyric obscenity, both erotic and rhetorical.

The huge sky over the working harbour felt home-like.

You had fallen upon the situation where the designation “speculative” functioned as insult.

The I-speaker on your silken rupture spills into history.

Feminism wants to expand the sensorium.

The overpass hums in you all night as you sleep.

Once again and with mild exhilaration you acquire a new surface.

The peculiar indwelling of rime was a roving organ.

In the old studio photograph your lipstick is black.

The perceiving is for yourself, but meets at no doctrine of the subject.

You’d rather be a dandy than a writer.

The pleasure in leaving those quiet rooms!

O Sir, you said, had I only been able to tell a quarter of what I saw and felt beneath that tree.

The pools of bile on the floor of the operating theatre glinting beneath heavenly lamps.

Now you know that all along it’s been the body that you don’t understand.

The present is all with you.

You won’t assume that in your century the darkness is necessary.

The problem is not your problem.

Your historical pleasure was metrically interrupted by the inadequacies of terminology.

The problem of solitude, what was it to you?

At dusk the light through the branches was enough.

The question for you becomes what are we doing with our bodies?

You haven’t enough time to believe anything but the comedy of sensing.

Cover art by Ian Friend

Cover art by Ian Friend

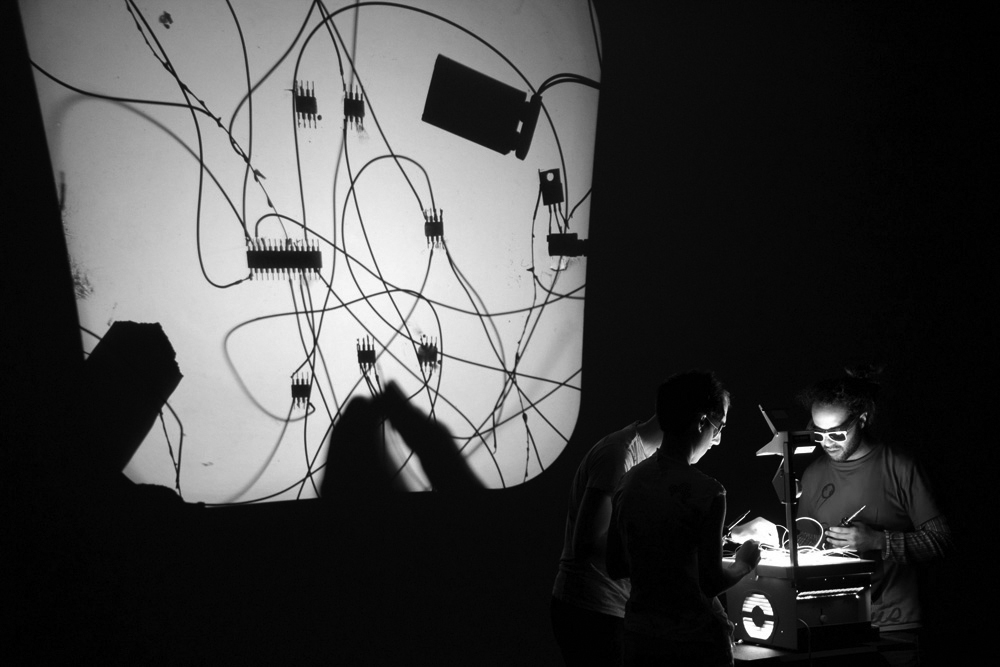

Image by Juno Gemes

Image by Juno Gemes

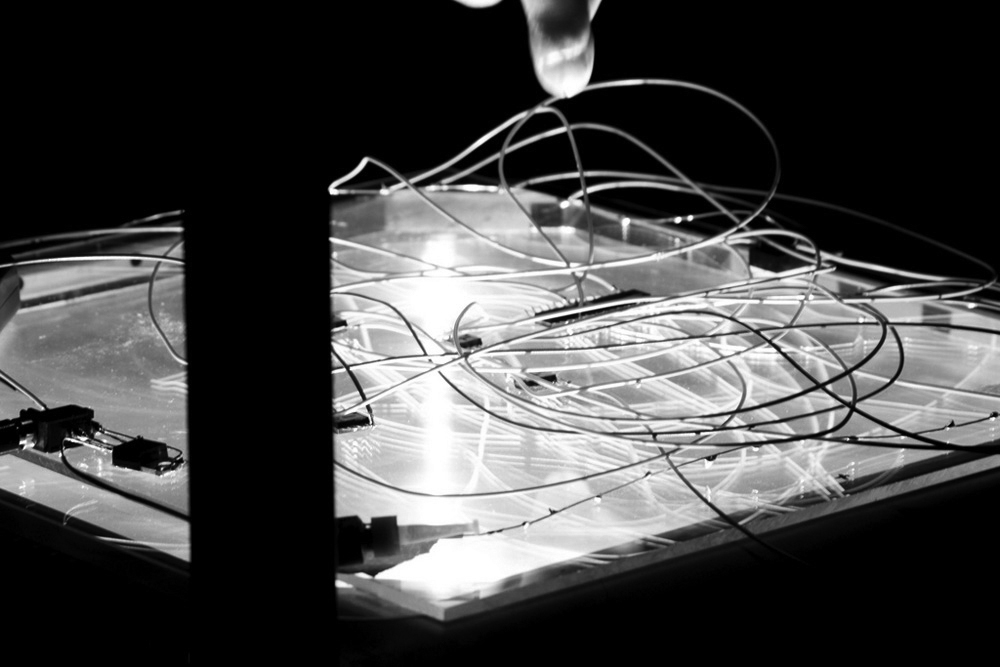

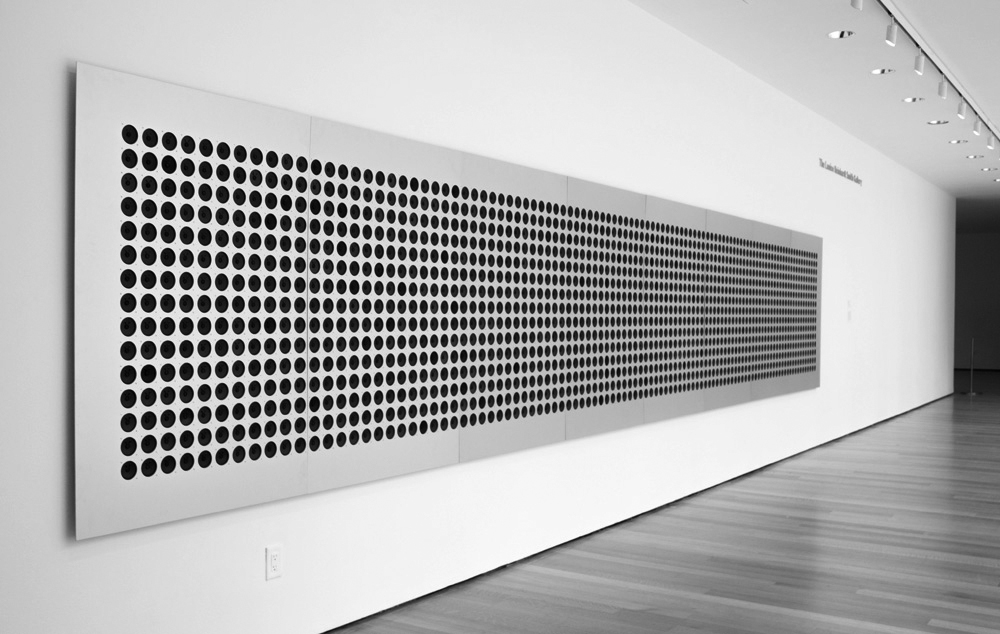

Image courtesy of Tristan Perich

Image courtesy of Tristan Perich

Image courtesy of Tristan Perich

Image courtesy of Tristan Perich