Image courtesy of The New York Times.

The Poets

(Extract)

Poets who love.

Poets who love Greece.

Poets who want to be loved and when they are, immediately leave poetry, relieved.

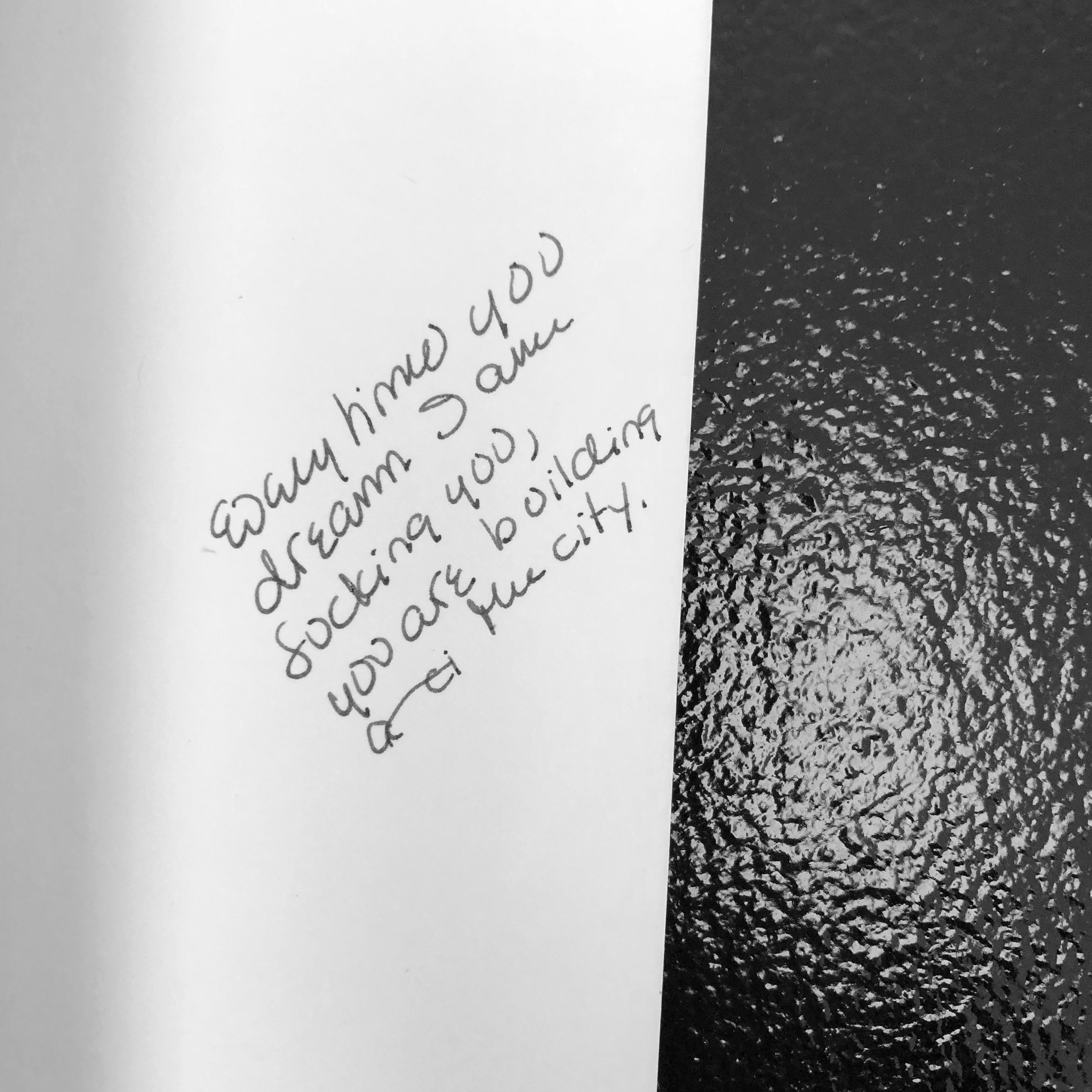

Poets who write their phone numbers into poems.

Poets who have no words for it.

Poets at parties dreaming of bright solitary spaces.

Poets in bright solitary spaces dreaming of parties.

Poets cutting lemons in the dark.

Poets in long columns on a long march.

The poet’s fascination with snails, which have both penises and vaginas and stab each other with calcium arrows before they mate.

The poet’s tears when he takes her sex in his mouth.

The poet who wants be tough, so she buys a leather jacket and sits on a motorcycle and fucks a girl who comes from a little village and writes poems about it, feeling the power crackle from her fingertips like lightning.

Poets who plan bank robberies with their poet friends. 10 downtown banks are to be robbed at the same time, so at least some of the poets can escape in the confusion. In the banks they plan to leave poems (bad idea).

…

The poet smiling at grasshoppers.

The poet investigating the poetics of hotels.

The next destination always seems more appealing to the poet than the place she is in. The previous stops seem more attractive the further away they are.

The poet’s face when she realises that she can never come home. That there was never a home to begin with.

The poet holds an important post at the institute of longing.

The poet feels bored, wherever she is.

The poet’s noble melancholy, one final remnant of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The poet imagining the future of golf pants.

The poet in his bathtub, like a cruise ship anchored in a deep fjord.

The poet, with the superiority of the penniless, towering like a lighthouse on the outermost point of her feelings.

The poet, with the anxiety of the ill adjusted, writhing like a worm in the intricate maze of his mind.

The poet with milk in his beard.

The poet with her foot on the gas.

The poet with his young male assistant.

The poet with the daughter of the cook.

The poet with her face in her hands.

The poet with her PhD.

The poet with gloves on, breaking into her own house to claim insurance money.

The poet with his finger on the Ouija board.

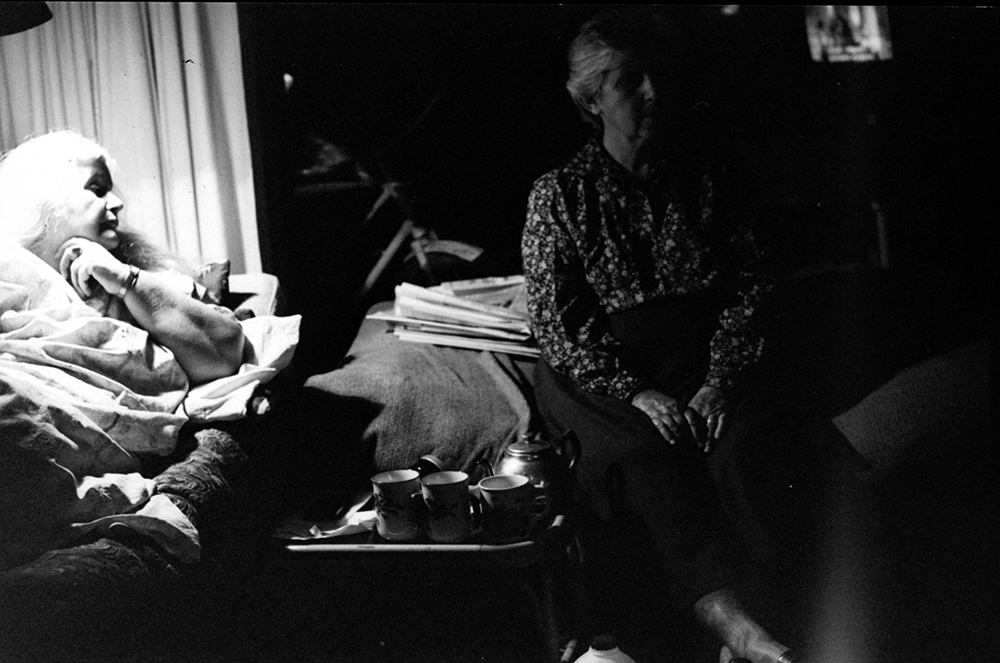

The poet evoking in daydreams all the houses she ever lived in. The living rooms, the bedrooms and kitchens, the furniture, the view from the windows. The poems she wrote in those houses. Finally, the daydreams she had in each room.

The poet prefers texts in which the I (if there is one) is a fluid I. An I capable of assuming all positions, masculine, feminine, young, old, human, animal, leaf of grass, tectonic plate, one after the other, or simultaneously. A doubting, searching, aspiring self. A furious, calm, expectant self. A little gnome-self during World War 2, safe and sound by the fireplace.

The poet who refuses to give up. Bald head bent over the white paper, which he slowly fills with prepositions, conjugations of God.

The poet’s ferocity, tamed by his obligations to a girl he adopted from China, shortly before 9/11 ruined the idea that he could give her peace and security.

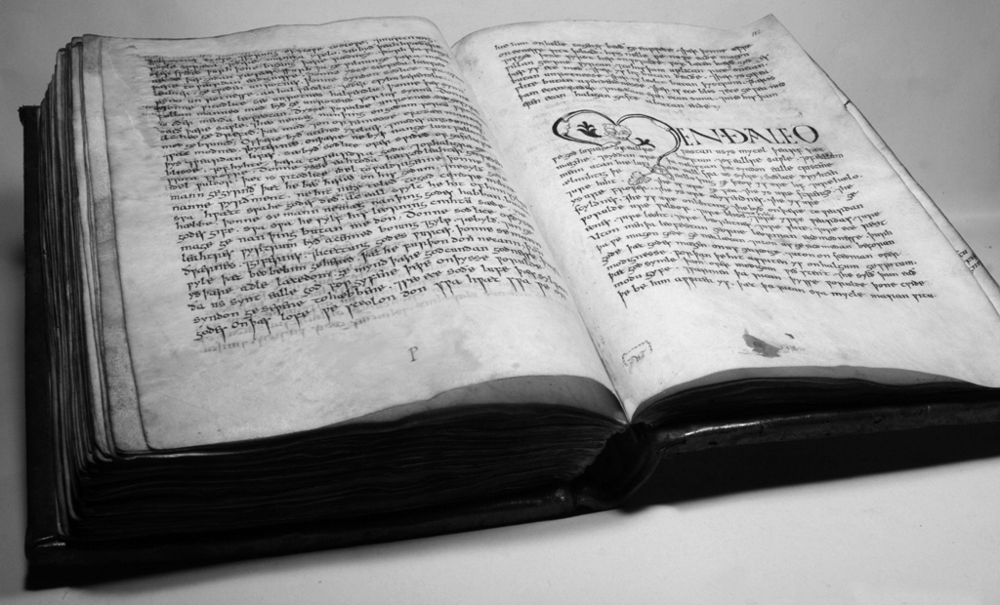

The poet’s vanity and notions of an afterlife, the meticulous letters addressed to friends, publishers, critics, but written with the dark shelves of the national library in mind.

The poet’s late realisation that a lifetime of antagonism towards a particular critic was the fire that kept his poetry going.

Poets interested in what happens when you take psychotropic drugs.

Poets interested in what happens in the days after taking psychotropic drugs.

Poets who argue that Poetry is far wiser than any poet, wiser than anybody.

Poets who write about the dark side of Chinese society.

Poets who identify deeply with Glenn Gould and Joseph Cornell.

The poet who consciously works to destroy the memory of his privileged upbringing, burns all his bridges and ends up in a foreign country where he becomes a guru for a bunch of drug addicts who find solace in his limitless self-hatred.

Poets who win awards and develop an artificially inflated self-image they can then use as an excuse for new assaults on the language. Trembling cadence fever, grandiose metaphors.

Poets who win awards abroad because translation conceals the violent assaults they have committed on their mother tongue.

Poets whose sensitivity to their mother tongue is so intense that it can never be translated.

Poets who are hurt when the public recognition they so despise passes them by.

Somebody nudges the poet in the movie theatre. He must have fallen asleep. Maybe he was snoring? Why else would they nudge him?

The poet at night, studying the trees in empty parks.

The poet in the morning, studying the landscape of the duvet.

The poet puzzled by the existence of moose.

The poet a jar.

The poet’s meticulous account of the comings and goings of swifts, their numbers and behaviour.

Poets who write long suites about the wind or the sea.

Poets who write poems with the help of google searches.

The internet poet is to literature what the cafeteria is to the school system.

The romantic poet is to literature what the butterfly is to the butterfly effect.

The three poet friends who invent a fourth, fictional poet who puts an end to their friendship.

Poets who are late for appointments.

Poets who sign petitions for peace.

Poets who help out in Haiti.

The poet, married, with 2 children and his own house, ranting against the petite bourgeoisie, seeing himself as a revolutionary anarchist and blaming other poets for being apathetic.

The convenient self-deception of the poet.

The poet who falls down, down, down in a dream with a lot of other people and chairs and tables in a kind of waterfall.

Poets meeting amid a swarm of bees.

Drunk poets playing long table tennis tournaments without a ball.

Poets undressing, fully.

Poets hiding inside the Trojan horse.

Poets jumping on wrecked cars in the morning sun.

Poets discussing the difference between having friends in literature and having friends in real life.

Poets discussing whether they’d rather be burned alive or eaten by a shark.

Poets being kicked out of the art gallery after having sex in the bathroom.

Poets, somewhere near a tennis court at night, feeling lost in life, but life knows exactly where they are.

Poets gathering around a bonfire with their favourite books, one brings Inger Christensen’s Alphabet, another John Ashbery’s Tennis Court Oath, someone else brings Pieter de Buysser’s Landscape With Skiproads, each of them explain what this book means to them, how it inspired their own writing, led them to new awareness, and then they throw the books in the fire. All meaning transformed into heat, the original hunt for the right words, mirrored in the syncopated dance of flames over smoking pages, fire as the ultimate reader.

Poets by the lake, mimicking titles of famous novels for the others to guess.

Poets disappearing as calligraphy over the ice.

Poets chased by the shadows of clouds.

Poets imagining life as an artist, selling a lot of art and having a house in Spain.

The poet watches the path of ants through the kitchen.

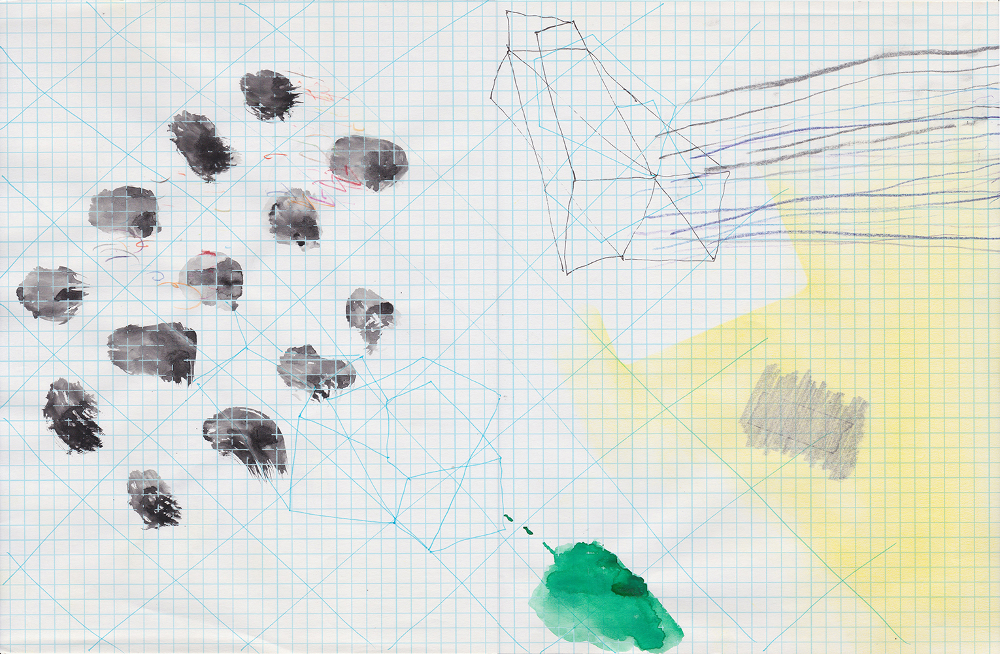

The poet imagines the bookshelves are high-rises and each book is an apartment full of word-people, living side by side, infinitely close. In this metropolis of meaning, new landscapes, smells, feelings, ideas open up with each millimetre, in every direction.

The poet imagines all the pregnant women on the street in New York suddenly breaking into synchronised dance, like in a musical.

The poet exits a dark stairway, feels the cold, dry air. The steam from a dog’s tongue.

A dog the poet has never known has sighed.