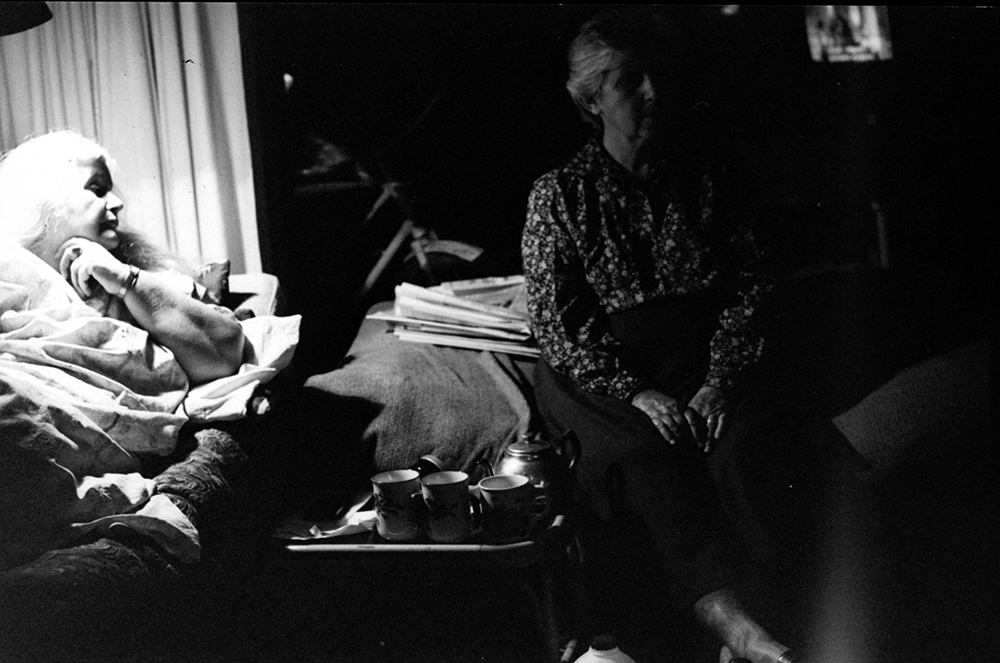

Courtesy of the Archive of Lesley Dougan.

An indelible part of the Brontë mythology is their symbiotic development as young artists in an isolated environment. Some time ago, Juliet Barker’s biographical scholarship on the culture at the parsonage and the Brontë siblings’ lives in Haworth has questioned that isolation in terms of the rich resources available to the Brontës siblings and a family culture that strongly encouraged their imaginative and artistic development.1 More recently, director Sally Wainwright’s TV movie To Walk Invisible has meticulously recreated the dynamic relationship between the Brontës’ childhood fantasy worlds and their adult writing, along with the strategic ways in which the three sisters built a professional path towards their lives as novelists directly through their sibling bonds. Wainwright’s interpretation of the sisters’ creative lives has gone some way in recovering both the weirdness and the ordinariness of the Brontës in it they seem closer (more graspable) than in any recreation of their lives encountered before. In a similar fashion, Simon Armitage’s recent engagement with Branwell Brontë’s life and legacy achieves, I think, a similar thing. As critic Drew Lamonica Arms has noted

(f)or the Brontë sisters, home – and no place like home – offered the liberty to be together and to be themselves, and this meant the freedom to write. Writing in collaboration reinforced the Brontë’s sense of family solidarity. It was also a means by which they established, asserted and explored individual difference among siblings cast in the same mould, raised in like circumstances and spaces, placed in similar life experiences as daughters, sisters, governesses and authors, whose devotion to one another was both profound and intense (96-97).

I want to consider the significance of the space of childhood in the creative development of Australian poet, playwright and novelist, Dorothy Hewett (1923–2002) through the lens of the childhoods of the Brontës by tracing connections between isolation, place, physical freedom and family culture in relation to artistic development and identity. I want also to think about the role of sister relationships and the influence of parents within the context of isolated upbringings.

In her revisionary introduction to Wuthering Heights, Charlotte Brontë attempted to excuse the perceived scandalous nature of that novel by stating that it was ‘hewn in a wild workshop’(xxiv). Whilst one can see the ploy behind this statement – Charlotte Bronte’s attempt to cast Emily Bronte as a naïve primitive in order to fend off accusation of unseemly writing for a woman – the designation ‘wild workshop’ is handy to my purpose in that in suggests the combination of a space and an activity that is separate from the day-to-day world. It also brings together seemingly contrary orders of a space that are potentially both disordered (wild) and ordered (workshop). In this way, in this tension, it ultimately describes a psychic space as much as the moors of Yorkshire or Lambton Downs, the 3000-acre wheat and sheep farm in Western Australia on which Hewett spent her formative years.

That first spaces define and haunt artists is a well-established notion. Janine Burke argues in her book Source: Nature’s Healing Role in Art and Writing, that this is practically the driving force behind many artists’ adult output – and that to lose the first place is almost necessary. The Brontës, perhaps more than any other writers, symbolise this extreme connection to childhood haunts. Emily Brontë in particular is figured as being earthed in the domestic life of the parsonage and its surrounding moors and of hating time spent away from there. Bruce Bennett argues that Hewett shares with other Western Australian authors such as Peter Cowan and Tim Winton an ‘organic’ notion of local environments also shared by English writers such as D H Lawrence, the Brontës and Wordsworth. Of Hewett he writes, the ‘imagery of place and especially of remembered places of childhood is a necessary prerequisite to the figuration of human behaviour and action’ and that this connection to writers such as the Brontës gives her work ‘an inter-textual richness and force’(20). This particular nexus of intense connection to childhood home, the positioning of that home as extremely isolated, to missing that home, and to the bonds of both sisterly affection and competition would, I argue, bring this sense of a Brontëan haunting to the artistic formation and identity of Hewett.

- For pioneering scholarship on the Brontës’ juvenilia see Fannie Ratchford’s The Brontës’ Web of Childhood (New York: Columbia University Press, 1941). The foremost contemporary scholar in this field is Christine Alexander. ↩