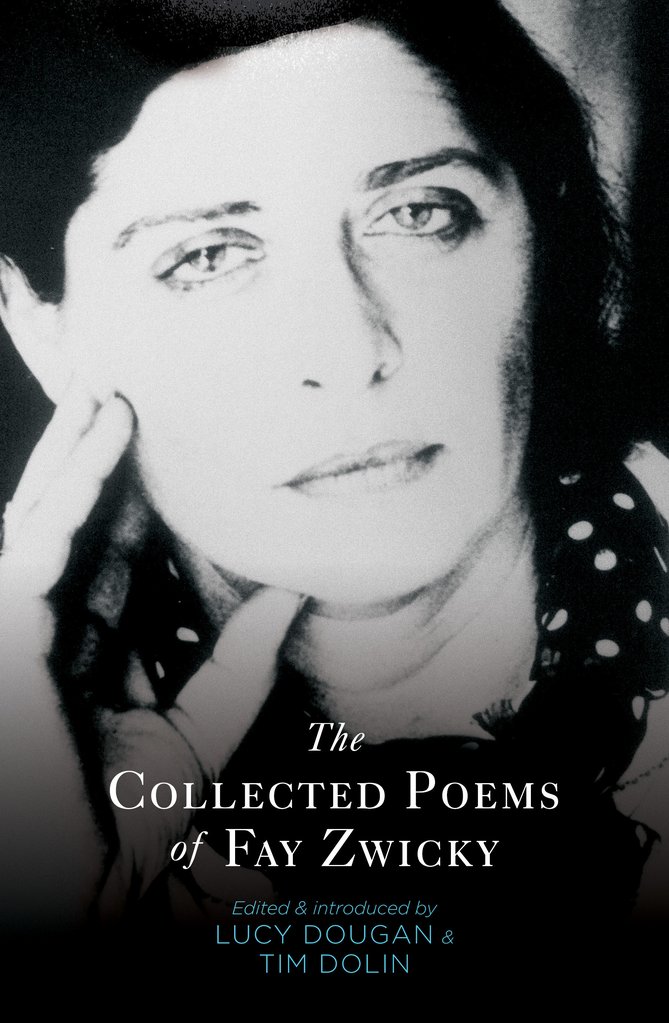

The Collected Poems of Fay Zwicky

edited by Lucy Dougan and Tim Dolin

UWA Press, 2017

On 2 July, 2017, my father sends me an article about Jewish Australian poet Fay Zwicky’s passing in Perth. I am four months into my Masters in Brisbane, where I am writing a manuscript of poetry and a thesis about tensions between my Jewish identity, memory, mental illness and hybridity as mediated through cultural objects and poetry. Fay Zwicky is one of my contemporary case studies and as I read through the article, I discover that the day before she died at age 83, The Collected Poems of Fay Zwicky was published, spanning her life’s work.

After long silence my broken world sits sweet with memory, its beauty dries my tongue ‘In Rehab’

Including seventeen uncollected poems at the end of the collection, The Collected Poems of Fay Zwicky also contains her previous works Isaac Babel’s Fiddle (1975), Kaddish (1982), Ask Me (1990), The Gatekeeper’s Wife (1999) and Picnic (2006), in order of publication. An introduction from editors Lucy Dougan and Tim Dolin gives insightful context to her works, as does Zwicky’s important essay ‘Border Crossings’ (2000). Both the introduction and ‘Border Crossings’ are pertinent additions to the collection as they discuss Zwicky’s cultural background and the Jewish rituals that inform her poetry.

The Collected Poems of Fay Zwicky shows Zwicky’s style evolving from her earlier poems. However, there are still strong connections between these early and later poems; this is made particularly evident by the presence of Jewish motifs. Weaving together Jewish references through her witty, often-rebellious voice and her play on language, these can be traced back to Zwicky’s first collection Isaac Babel’s Fiddle. The title poem, ‘Isaac Babel’s Fiddle Reaches the Indian Ocean’ contains an extract from Babel’s short story Awakening and opens with Zwicky’s lines:

Just try and cast a piano In the sea Romantically. Take it from me, you’ll Never make it.

Her voice rises to the fore in Kaddish, which brought her international recognition, and continues powerfully throughout her later collections. Drawing on her training as a classical pianist, Zwicky’s poems have musicality, rhythm and revel in sound, giving voice to women and minorities previously silenced by history. In her series ‘Ark Voices’ from Kaddish, Zwicky speaks through Mrs Noah and animals such as the Hippo, Wolf, and Whale. Her uncollected poem ‘Domestic Architecture’ heralds back to this theme, also evident in the title poem from The Gatekeeper’s Wife:

Severed from my ancestors I light a candle for you Every night inside a clay house. Memory is only half the story.

In ‘The Terracotta Army at Xi’an’ in Picnic, Zwicky lets the voiceless Emperor Qinshihuang, the spear bearer, the cook, the farrier, the archer and the potter speak through poetic monologues. Dougan and Dolin write in their introduction that Zwicky had a fear of being unable to speak and of losing her voice. In ‘Ask Me’, Zwicky explicitly references this anxiety of speechlessness as the speaker crosses China, America and Australia:

It’s the year of the Dragon. Omens for the journey aren’t encouraging. No language and I’m booked on China airlines. In Hong Kong I dream that I am born without a tongue and wake up screaming… —excerpt from ‘China Poems 1988’, part 1 ‘Roosters and Earthworms’

Of all Zwicky’s poems, her title poem from Kaddish best showcases the Jewish motifs displayed throughout this collection, and her reconfiguring and refreshing of language and ideas. ‘Kaddish’ is an elegy for Zwicky’s father and one of her most famous works, which took eighteen months to write. Drawing on Hebrew from the Jewish Mourner’s Prayer (the Kaddish), Zwicky also references the Passover song Had Gadya (One Little Goat) and turns the words upside down, making familiar melodies unfamiliar through metaphor. As I have recited the Passover songs every year since childhood, Zwicky’s inversion of Had Gadya is like a spot-the-difference game of rearranged fragments.

Zwicky credits the authors and influences that helped her find a voice in the 1970s: the Jewish American novelists Bernard Malamud, Saul Bellow and Philip Roth, whose work gave her a community that she felt she lacked in the Australian context. She also discovered Allen Ginsberg’s poem ‘Kaddish’ seventeen years after it had been published, and this was the breakthrough that made her feel freer to finish writing her own ‘Kaddish’.

For Zwicky, poetry has always seemed to be ‘a source of hope, a means of speaking against an orthodoxy, be it religious, political, or social’. Featured at the end of the book, Zwicky’s new and uncollected poems continue in these modes. For example, in her poem ‘In Rehab’, Dr Kiberu asks ‘are you religious?’ and Zwicky writes ‘I could be but not so you’d notice’. This line intersects with Zwicky’s major themes of Jewish identity in her earlier collections and is one that resonates throughout The Collected Poems of Fay Zwicky.

As a Jewish Australian woman writer, I am grateful that Zwicky has shown the possibilities of poetry for others to follow. The Collected Poems of Fay Zwicky is an extremely valuable addition to literature and a beacon for minority women’s voices to continue to break conventions, write and speak out.