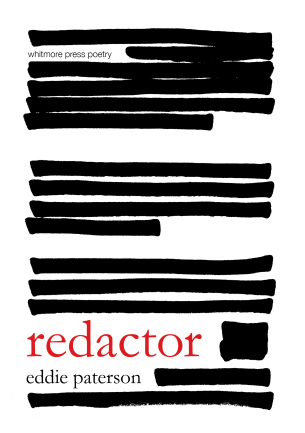

redactor by Eddie Paterson

Whitmore Press, 2017

As a physical object with an online extraction, Eddie Paterson’s new book of poems, redactor, presents the performance of mark-making in an ever expanding digital sphere. The juxtaposition between the white of the page and the black of the ink has long provided a site for textual collision, one that was used to great effect by the concrete poets and the French Symbolists. Out of the deep web’s detritus, Paterson’s collection discovers new poetic spaces of beauty in the banality of our metadata.

As feeds refresh and emails are automatically vetted for junk, redactor reclaims writing that would otherwise be lost, all the while preserving the decadent excess of digital information and communication, as the reader traverses the ‘aisleform’ of images that fit-out the collection’s mise-en-scène. Whilst found poetry and cut-ups, epistolary poems, and lyric monologues are all present in this collection, Paterson affirms a poetics of attention in the context of a superabundance of cultural production, naming his way through film titles, basketball players, critical theorists and fashion accessories. Paradoxically, the poetic practices of attention-grabbing and attention-holding are best exemplified by Paterson’s with-holding, embodied by the black mark: the redaction.

That the redactions are not random and that they are persistent throughout the collection remind us there is one actor performing. This redactor (or (red)actor) elicits a verfremdungseffekt by creating distance between the ‘i’ of the poem and the reader as the Brechtian directive suggests. By obscuring names and gendered pronouns, the Rimbaudian je est en autre is here remixed to establish a subject that, much like an online avatar, is capable of transcending the limits of the physical. This evasive performance of subjectivity negates the possibility for a reader to experience direct empathy or cathartic transference with the speaker and correspondingly the stage is cleared for the creation of an elaborate aesthetic through language.

In the same manner that Basquiat’s strikethroughs inevitably highlight the partially obscured text on his canvases, Paterson’s redactions demand the reader’s attention by their suggestion of silence in the steady flow of (non-acoustic) monologue. Formally, the monologues (and implied dialogues) in redactor are performed through statistics, articles, emails and instant messages. When Truman Capote slurred the work of Jack Kerouac as typing – not writing – few could have anticipated the personal computer (and by extension the smartphone / tablet) and the impact that these online typing machines would have not simply on creation, but on communication. Reading the physical copy of redactor as an anthology of calls and responses apprehended brings the audience into the immediate moment of poetry. The performance of creative writing in Paterson’s world becomes an instantaneous and embodied process of text communicated: generated as fast as the fingers move and read as quickly as the broadband connection allows.

Some wonderful blurring of the physical and digital occurs in redactor, particularly in the incantatory displacement of the poem ‘alert, but not afeared’. Beginning, ‘do not be alarmed. eddie the computer has taken on a life of its / own’, this poem equivocally warns a human about the improved capabilities of AI and / or assigns a subjectivity to ‘eddie the computer’, granting it its own non-gendered pronoun.

The aptly titled ‘rhetoric’ makes the case for reading the digital stage into this collection. The poem assumes the guise of an email / instant message that ends, ‘it’s about how it’s your birthday & i / really wanted to say happy birthday. happy birthday’. Informed by J L Austin’s theory of the performative speech act, this poem performs the birthday wish without the requirement of some other place or platform for the speaker to say happy birthday. Equally, ‘verfremdungseffekt’ is not just the title of a poem, but the actual enactment of what it purports.

This passage from ‘flow’ provides an insight into Paterson’s ironic displacement of the actor, as clothing is raised to the level of costume:

trivia night punk dressing went well though, as suspected, the intellectual deliciousness of a person who identifies strongly with the punk dressing up as a fake punk was lost to all.

Filmic titles used throughout the collection time-stamp the poems, but also suggest mise-en-abyme. In ‘just to the right of the heart of it’ the speaker’s re-watching of the film ‘Robocop’ is an important marker between the ‘hysterical garbage’ of a contemporary alien invasion film ‘battle: los angeles’ and the ‘white ribbon xxxxxx films about nazi germany i generally don’t see’, both temporally and aesthetically. ‘Robocop’, as part-man/part-machine, suits the collection’s liminal treatment of the physical/digital by being neither dazzlingly post-modern nor pretentiously modernist. One can imagine the cyberpunk action hero redactor in its kitsch late-eighties resplendence tearing through a warehouse of digital correspondence brandishing a black marker.

The final poem in the collection, ‘love poem’, offers the best synecdoche for redactor. ‘love poem’ consolidates the collection’s aesthetic accretion of stuff, taking ownership for every aforementioned movie trilogy, serialised drama, basketball statistic, kitsch accessory and instruction manual. Heaping one reference upon another, Paterson shows how the accumulation of language can be purposed to build a wall for the actor to hide behind. As the poem continues one realises Paterson is not only assembling imagery, but also building toward a dramatic conclusion, eventually breaking this fourth wall with the poem’s final couplet:

have optimus prime wolf parade david hockney roman holiday have playtime leave me with the park with the sun & that afternoon when unexpectedly you moved away from kafka & toward me.

In a collection where ‘russel crowe’ (who ‘consistently brings us to tears’) and ‘hugo weaving’ (who stars in a poem ‘no one seems to get’) feature prominently, Eddie Paterson, emerges at the close of ‘love poem’ as an Australian leading man, capable of a deft and show-stopping performance.