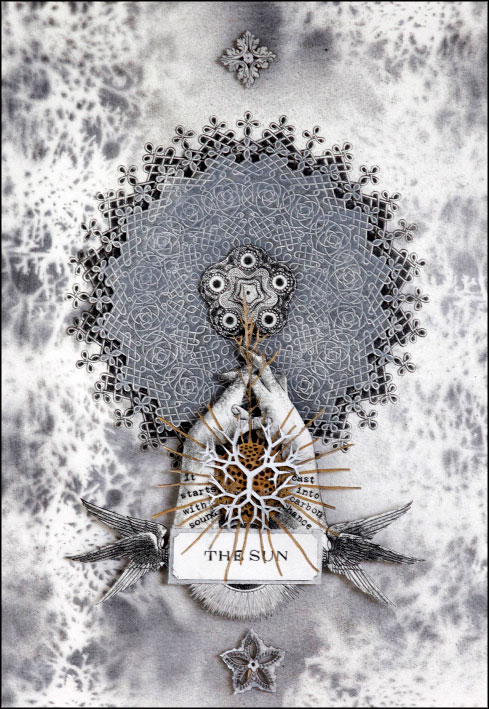

Conjoin | Hannah Raisin and Will Heathcote | Archival pigment print | 75cm x 50cm

Conjoin | Hannah Raisin and Will Heathcote | Archival pigment print | 75cm x 50cm

There is No Such Thing as a Good Poem about Nothing

There is no such thing as a good poem about nothing? What does that mean, exactly? And what’s all this about spoon bending anyways?

Not long ago, Australian literary critic Andrew Riemer slept-walked through the writing of his take on Best Australian Poems 2013 (Black Inc., 2013), edited by Cordite Poetry Review’s Feature Reviews Editor, Lisa Gorton. In his review of this most recent volume of the annual institution, Riemer lurches around the pachyderm – or one of a small parade – in his writing room, then coaxes it out to greet the reader midway through his assessment: ‘Apart from poems by several older, well-established poets – Les Murray, David Malouf, Vivian Smith, Geoffrey Lehmann and Thomas Shapcott, among others – most of these poems lack distinctive voices, a poetic sensibility, in other words’. If that isn’t a trunk-full of mucous water sprayed right in the kisser, then nothing is. His words seem to attest, then, that Australian poetics is / should still be defined by the storied careers of a few older, mostly white men (and a few women) … or, at least, his review supports the existence of such a lens that’s been ossified into place from a few vantages around Australian letters.

Irrefutably, the writers Riemer mentions have made and continue to make an enormous and significant contribution to Australian poetics. But, as the Best Australian Poems 2013 presents so well, there are a few well-accomplished whole generations of poets sharing this grand parade – including new poets right now, a most exciting bunch, many with generally perpendicular approaches to poetry than the aforementioned legacy poets. Riemer’s assessment of the anthology then ricocheted – via quite an arresting display of (con)textual ‘physics’, in high dudgeon and 3D! – clean off the surface of one of Australia’s most important indigenous poets, Lionel Fogarty, deeming his poem to be ostensibly ‘meaningless’, instead of representative of the deft post-colonial narrative origami that is Fogarty’s mastery. Entitled to opinion? No, I don’t believe in that. I prescribe more to the entitled-to-what-you-can-effectively-argue-for school. Consider these opening lines from Fogarty’s poem ‘Induct True Legendary Thrills Bravery’, included in Best Australian Poems 2013:

Bravery captors medal heroism circulate mission leftovers

Bravery tracks the saddle that throws sad off backs as

Honour full bloods across country’s rescues

Replica escorted stream afield sees gallantry

Riemer did not effectively argue these exemplar lines to be ‘meaningless’ (in fact, he made no attempt at all). What struck me most acute about this review-as-provocation was a response to the review itself; arriving as it did via Melbourne poet Bonny Cassidy on the Puncher & Wattmann small press blog a few weeks hence. In her reply to Riemer’s review, Cassidy wonders:

‘Seriously, when are we going to accept that poetry, like painting and music, may represent ‘patterns of utterance’ rather than figurative lines? Riemer seems to suggest that poems that ‘do not yield sense in conventional discursive or grammatical terms’ are so radical that they escape ‘literary or poetic tradition’.

‘Patterns of utterance’ – primal and archaic – Riemer chalks this up as failure. Yet Cassidy’s jujutsu reply is sound. Astute. Succinct. Tart. Deserving … and not altogether un-damning. I’ve spent years trying to proffer this exact question as well as Cassidy has. US poet and esteemed teacher, Theodore Roethke, put it a more florid way, ‘You’ve got to have rhythm. If you want to dance naked in an open barndoor with a chalk in your navel, I don’t care! You’ve got to have rhythm.’ Patterns of utterance = rhythm.

What, indeed, might Riemer make of Mark Rothko’s Sacrifice of Iphigenia, 1942, let alone the later No.4, 1964? Congruent motivations can be applied to poets as Rothko once wrote of painters in his famous letter to the New York Times – rebuttal to a poor review and co-written by Adolph Gottlieb and Barnett Newman: ‘It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints, as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academicism. There is no such thing as a good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess a spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.’ The wide gulch, then, is Riemer mistaking something for nothing (‘more than ink on a page’, as he couched it) – in a number of the poems Gorton included – at base levels due to the near dearth of conventional discursive bridges linking those ‘some things’ together and failing to recognise the conduit that funnels abstraction into concept.

If we strip away the technology of lyric, we are left with the archaic. As Australian poet Peter Minter says in his introduction to ‘Proteaceae: A Chapbook Curated by Peter Minter’ for Cordite’s GONDWANALAND issue, and in referencing Australian painter John Wolseley:

‘Wolseley’s artwork shows how plant species such as the beautiful red waratah … have archaic affinities with similar species around the planet. This profound geo-aesthetical encounter reminds us of an embedded planetary and genetic inheritance that, despite the complexities of our technologies and linguistic apparatuses, is always and unescapably experienced ‘in common.’

The plug of Minter’s elemental ‘archaic affinities’ elides perfectly into Rothko’s ‘primitive and archaic art’ socket – the connectivity produces art, no adaptors are necessary (but optional, and interesting, so go for it you want to). How did this imbalance, the perceived sophistication of one approach over the other, become so entrenched? Or are Riemer’s thoughts the sinews of a loner puma? Perhaps. At any rate of conjecture, Australian poetics – or at least the expectations of it from a wider literary audience – feels to be slowly snapping out of its generational-ideological imbalance toward a trued scale. For this chapbook, I’ve asked writers from a number of other countries to contribute.

So, in hypothesis, what would a kindred holder of Riemer’s conclusions on art think of Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep? Kraftwerk’s Autobahn? Michel Butor’s Mobile? Amaranth Bosruk’s ‘Between Page and Screen’? Kurt Schwitters, anybody?

Returning to Cassidy’s question, ‘… when are we going to accept that poetry, like painting and music, may represent ‘patterns of utterance’ rather than figurative lines?’, I got to thinking – thinking about spoon bending, about the nature of words-as-objects and how words’ multiple definitions, idiom and pronunciations distil as a unique ‘atomic mass’ of sorts, bundled with a litany of alchemic delights. Can a story also be told from the lexical reactions made simply by placing seemingly disparate words near each other? Might they reverberate and hum when they become too near? On one plane, perceptibly nonsense; on a sub-plane, potential chemical fusion; and split apart from either plane, fission? Arguably, yes. Is this kind of narrative as worthy or rigid a discourse as those reliant on lyric? I think so, but the onus clearly shifts significantly away from (but not entirely) the infrastructure of a given language and settles squarely on the writer, the spoon bender, to harness and corral the developing poem’s force as she sees fit (incidentally, if The Portuguese has a subway, let me loose with tokens to ride). These are not new questions. But the problem remains: the legacy class of poets in Australia doesn’t seem to have much time for one of these two (generalised) approaches. Or perhaps the leaky beaker exists only in the experiments of certain reviewers?

Indeed, the hybrids of these styles – conventional discursive v. patterns of utterance – appeal to me a great deal (as do many poems that shake out more like 95% to 5%, from either endpoint). Consider these seven lines beginning ‘Georgia talks to a painter’ from Australian publisher and poet, Michael Brennan’s recent book Autoethnographic, an engrossing collection I am well overdue to deliver a review of to a fellow journal:

The way spirit tracks, in brushstrokes or words,

you’d have Buckley’s of getting it right, sensing

how out here light does not fall. Waves of images

fill you so there’s nothing but to paint, though

you don’t like it, this country that’s in you, the

red dust coating everything in one place or the

granite now, beneath your feet an island, quartz

I am especially bewitched by the invocation of the term ‘Buckley’s’, itself a classic Australian truncation / amputation from ‘Buckley’s Chance’. All Australians know what this means, and I’m going to leave it at that … but are any of you readers abroad piqued enough to research the massive idiomatic gravity so adroitly slotted into place here? I hope so. It doesn’t require much research.

For this online chapbook, I have intentionally included works that plot point along the full arc of the hybridisation I mentioned earlier. Adding to this solution, I have included translations of the originals (or vice-versa) for an extra layer of phonetic consideration and socio-definition. Russian, Turkish, Bahasa Indonesia, sprigs of Danish: combined with English, the tongues dissolve into a common blood of verse. These poems do not represent rigid binaries of approach, rather I aim to continue the discussion of a polyvocalic literature that spans generational governance – technologies, linguistics, poetics and patterns – of what a poem can be.

There are too many things to say about Guillaume Apollinaire’s ‘

There are too many things to say about Guillaume Apollinaire’s ‘

Conjoin | Hannah Raisin and Will Heathcote | Archival pigment print | 75cm x 50cm

Conjoin | Hannah Raisin and Will Heathcote | Archival pigment print | 75cm x 50cm