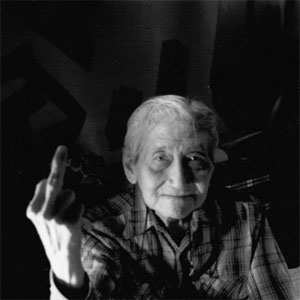

José García Villa, mid calisthenics | New York City, 1993 | Photograph by Eric Gamalinda | 35mm Kodak Ektachrome 100

In my teenage years, the poet José García Villa had withdrawn into legend and silence in New York, an absent god from whom only the occasional witticism was relayed to Manila. In 1973, when my adolescence was coming to an end, he was 65 and teaching at the New School for Social Research. I would have been surprised had I been told he was still working. From his first American volume, Have Come, Am Here, that made his reputation in 1942, his poems mentioned nothing specific to the Philippine milieu. They continued to fascinate Filipinos who came across them, but his celebrity preceded his poems. Whether or not we had read them, he intrigued us as the only Filipino who had made it into the metropolitan literary pantheon; his inaccessibility in New York did nothing to detract from his glamour. I don’t recall when I first read Villa. Very likely he was included in the English Lit. reader in Philippine Science High School, the selective school I attended for two years. His Selected Poems and New and one or two pamphlets were in the library of the Ateneo de Manila University, where I went to study after finishing high school in my province. I grazed on them, not having learned as yet to read poems closely even though I was drawn to poetry.

Villa was born in 1908, in Manila proper, and grew up in the professional district of Ermita, a large portion of which was owned by his mother. Villa’s doctor-father Simeon was – like Don Lorenzo Marasigan, the reclusive painter in Nick Joaquín’s play A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino – one of the embittered men who had invested the most intense years of their lives in the revolution and wound up shipwrecked in the American Century. The war against the Americans was the revolution’s second phase, and Col. Villa was a devoted aide of Emilio Aguinaldo, President of the new Republic declared in 1898. After the war shifted into guerrilla warfare, he and Aguinaldo eluded the Yanqui invaders for more than a year between 1899 and 1901. They had hiked a zigzag route through Luzon, north along the western coast, west to Bontoc, then south, climbing mountain paths from which horses fell to their death. Then, through cold and fog and thinning air, the weakened men struggled on their hands and knees, to Banaue, of the steeply terraced slopes, then down to the fertile valley of Isabela, then up again north through the Gran Cordillera’s high pine forests and jungle and tribes jealous of their domain, to mountain-locked Abra, where in a small town on 22 March 1900, they celebrated the President’s 31st birthday.

A few weeks later they pulled out to hide in the forest from American troops. They trekked south, then westward across the wide valley and its rivers, across the Sierra Madre, and came to a stop in Palanan, overlooking the Pacific. Here Aguinaldo was captured – together with Col. Villa – on 23 March 1901. It was due to the colonel, in fact, that the Americans discovered where they were hiding.1 Appointed Chief of Staff, Simeon had been chafing at the peace and quiet of Palanan and requested a military assignment. Americans intercepted the letter sent to his replacement, General Sandiko, and a contingent of tribal Macabebe scouts in American pay, posing as revolutionary soldiers, was sent to Palanan. Pretending to lead them was a Spaniard who had fought against the Filipinos, then joined them in the war against America and surrendered. Five Americans were disguised as prisoners being dragged along, one of them Colonel Frederick Funston, the plot’s mastermind. (Funston, a proponent of zero-tolerance in the war against the Filipino guerrillas, was chosen by Woodrow Wilson to lead the American Expeditionary Force in the First World War but died in a San Antonio ballroom before he could. He was replaced by John Pershing, another Philippine veteran.)

Simeon Villa kept a diary in Spanish – and in the third person – while he and his beloved president wandered the wilderness.2 In the photograph that fronts an English translation, he wears a white linen jacket and a tie of fine diagonal stripes of a dark colour (blue perhaps) and white or cream, and has the flat slightly prognathous face, high cheekbones and wide nose of his son José, but more soulful eyes. His son came to hate him. In 1929, when Simeon had become something of a recluse, the 21-year-old José, a student at the University of the Philippines, published a volume of erotic verse called Mansongs, for which he was charged with obscenity and fined 70 pesos by a court. The book may have offended a few stodgy readers but it won a prize (from the Philippines Free Press) and with the prize money José embarked for America, studying at the University of New Mexico before transferring to Columbia. In 1937 José returned to the Philippines, hoping to be given his inheritance in advance. In an essay for the Free Press, Nick Joaquín writes that the poet’s friends, Manuel and Lydia Arguilla, remembered his father coming to them and saying, ‘What is the matter with that son of mine? He is very strange. He does not want to live here; he wants to live in America. Why, is he an American? He wants me to sell our property; I cannot do that, I must think of my other children. Why doesn’t he settle down here and administer the property?’ The hat was passed around for José’s fare and he sailed back to the U.S. the same year. If he ever went back, the son remarked when he had heard of his father’s death, he would spit on the old man’s grave. On the rare, much-heralded occasions when the poet later returned to the Philippines, he was unable to carry out his promise. Simeon was killed when Manila was liberated from the Japanese and his body was never recovered.3

Joaquín imagines the conflict between father and son as essentially between two cultures: little English on one side, little Spanish on the other. The United States had begun shipping schoolteachers to the Philippines just four months after President Aguinaldo officially surrendered (in April 1901), when many Filipinos were still fighting the guerrilla war begun the year before. The shift to education in English was the start of the erasure – partly deliberate, partly inadvertent –of the hybrid Latin culture common to the leaders of the revolution and the propagandists before them. There were men who never lost their resentment of the new dispensation, and Simeon Villa seemed to have been one of them. The intransigence of the father became the son’s. The mature poems echo – defiant Self-glorifying retorts – in the transept of a provincial cathedral … stark, massive, baroque.

My most. My most. O my lost! O my bright, my ineradicable ghost. At whose bright coast God seeks Shelter and is lost is lost. O Coast of Brightness. O cause of Grief. O rose of purest grief. O thou in my breast so stark and Holy-bright. O thou melancholy Light. Me. Me. My own perfidy. O my most my most. O the bright The beautiful the terrible Accost.4

Villa had begun as a writer of fiction in the United States: his collection of short stories, Footnote to Youth, came out in 1933 and had stories set in the Philippines as well as in America. When he gave up fiction to devote himself to poetry, he also gave up empirical description, which was entirely absent from his poems. In his autobiographical statement in Twentieth Century Authors, he writes: ‘… I am not all interested in description or outward appearance, nor in the contemporary scene, but in essence.’ It was his realisation of this that turned him to poetry. His writing, from Have Come, Am Here (1942), was also divested of any concrete references to the Philippines. The poet was no longer recognisably a Filipino writer. Neither was he American. His poems flaunted their un-Americanness; his image-repertoire of bright shores and skulls, of antique ant and spiritual centipede, Christs and terrible heroes, was abstracted from the landscape and history of the country he left behind. This landscape and this history were not forgotten in Villa’s poetry, but they were present only as the blurred, indistinct background to his figures. In turning to poetry, he had not only turned away from empirical observation, from history and social milieu: he had discovered ‘the bright / the beautiful the terrible Accost.’ In the three sequences of numbered short paragraphs that compose the semi-autobiographical ‘Wings and Blue Flame: A Trilogy’ and in ‘Young Writer in a New Country’ (both in Footnote to Youth), he wrote of a young expatriate man’s loneliness in America (and romantic friendships with other young men), but the poetry glories in the Self. Villa alludes to this change in poem 63 of Have Come, Am Here: ‘The days of no address,’ he says, ‘or the days of interrogation/ Are gone./ Have found.’ ‘Migration’ now has ‘a focus/ An always-address.’ ‘Could have been Death,’ he says, ‘had not Love supremed me.’ And in what seems like a non sequitur, he declares that ‘the I is the Word.’5

When the poet-critic Randall Jarrell wrote his scurrilous review in 1949 of Villa’s Volume Two, he pretended not to know whether Villa was from Manila or Guadalajara, and imagined him speaking in ‘his warm, gentle, Southern way.’ Jarrell knew of Villa, had even met him, since they are both in that all-too-often-mentioned Gotham Bookshop photograph taken in 1948 on the occasion of Edith Sitwell’s visit to New York – together with Elizabeth Bishop, Marianne Moore (who had favourably reviewed Have Come, Am Here), Auden, Spender, Delmore Schwartz, Tennessee Williams, a young Gore Vidal. The Philippine poet was invited to the reception because he was something of a protégé of Edith Sitwell, who would write the introduction to his Selected Poems and New, published ten years later. Clearly, Jarrell thought of Villa as an interloper in the American scene, but neither Jarrell nor Moore nor his other American reviewers knew much about the life he left behind, nor of his influence on writers in the Philippines. When Villa returned to his native country in 1959, it was only for the second time since he left, but he regularly intervened in the local scene as a critic from the mid-‘20s and all through the ‘40s, posting his opinions of local fiction and poetry in English from New York, pronouncements awaited with fear and trembling in the Philippines.6 Among Filipinos, Villa acquired an aura of whimsy, provocation and sarcastic wit, an aura only partly gained from his poems. He became the famous Poet.

- As Nick Joaquin notes in A Question of Heroes (Pasig City, Philippines: Anvil, 2005). ↩

- Villa, Simeon and Barcelona, Santiago, Aguinaldo’s Odyssey: as told in the diaries of Col. Simon Villa and Dr. Santiago Barcelona(Manila: Bureau of Public Libraries, 1963). ↩

- Joaquin’s essay, ‘Viva Villa,’ is reprinted in Tabios, Eileen (ed.), The Anchored Angel: Selected Writings by José García Villa (New York: Kaya, 1999). ↩

- ‘68’, Villa, José García, Doveglion: Collected Poems, ed. John Edwin Cowen (Penguin Books, 2008), p.42. ↩

- Villa, José García, Doveglion: Collected Poems (Penguin Books, 2008). ↩

- See Chua, Jonathan, The Critical Villa: Essays in Literary Criticism (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2002). ↩