I once read that the word ikebana (生け花), denoting the Japanese art of flower arrangement, can be roughly translated into English as ‘living flower,’ or ‘bringing life to the flowers.’ This summary sounds too easy, too graceful; there is an air of internet mythology to it, the truth of it smoothed and polished like a well-handled stone until it becomes convenient, small enough to tweet or swallow. I don’t know Japanese, and even if I did, I doubt whether my clumsy English renderings would do any more justice to the words’ original elegance: to the 生 rooted in life, meaning raw, growing, being born – to the bloom of the 花 recalling cherry blossoms, paper petals, grass. But somehow, despite my ignorance or because of it, I find joy in the deconstruction of the word, in the Googling of its kanji, the deciphering, the re-making. The word ikebana is a little poem, and I am its fumbling, ill-equipped translator.

There is something in the symbolism of ikebana, the practice of it, that fascinates me too: after the fresh flowers are cut from the soil – their first, ecstatic death – they are given new life through the meticulous touch of an expert practitioner, or kadoka. I cannot help but interpret the flowers themselves as words and poems, the disciplined hands of the kadoka as those of the poetry translator. Forgive my romanticism. But there is precedent here.

Poems have often been thought of as precious, living things, precariously balanced on the precipice of language, the tension of their form and music exquisite, untouchable. The words of Percy Bysshe Shelley, recorded in his famous ‘Defence of Poetry,’ remain some of the most widely cited:

It were as wise to cast a violet into a crucible that you might discover the formal principle of its colour and odour, as seek to transfuse from one language into another the creations of a poet. The plant must spring again from its seed, or it will bear no flower – and this is the burthen of the curse of Babel.1

If a poem is a flower, then to translate it is to uproot it from its indigenous soil, to sully and defile it; ultimately, to destroy it. This makes sense, if we think of translation as an act of analysis, some kind of literary vivisection (at best) or post-mortem (at worst). Except poetry translators, for the most part, are not the heavy-handed boffins Shelley describes in his ‘Defence.’ Translators of poetry, especially when they are poets themselves, seek not to analyse but to re-plant and re-vive; they work in studios, not in laboratories. Indeed, they have much in common with the kadoka – they are sensitive, well trained, precise. They are in love with their wordflowers. They are life givers.

Historically, the translation of poetry has been shrouded in pessimism, represented in grotesque metaphorical terms as an act of cold, methodical dismemberment. From Paul Valéry, who described it as the unholy resurrection of ‘dead birds,’ to the sharp-tongued Vladimir Nabokov, who memorably likened the craft to taxidermy: ‘Shorn of its primary verbal existence,’ he wrote, ‘the original text will not be able to soar and to sing, but it can be very nicely dissected and mounted and scientifically studied in all its organic details.’2

The observation that ‘poetry is what gets lost in translation,’ tenuously attributed to Robert Frost, has become a sort of aphorism for those who delight in bemoaning the untranslatability of great literature. This line of thought (caustically branded by leading Translation Studies scholar Susan Bassnett as ‘self-indulgent nonsense’) perpetuates the post-Romantic myth that poetry is some ineffable thing, impossible to transpose or transplant. Modernist aesthetics most certainly complemented this frame of mind (although I must exclude here the example of Ezra Pound, himself a renowned poetry translator). In works of poetry, as the Modernist argument goes, form and content are inextricably wedded. A poem is therefore a poem by virtue of the words it is composed of, and the way they have been put together. For the Modernist aesthetician, there is no prior meaning to a poem, and therefore nothing to be translated; in the words of T S Eliot, ‘that which is to be communicated is the poem itself.’

In light of such perspectives, the task of the poetry translator becomes not only impossible but inconceivable. Consider, for example, the disheartening words of Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset:

Human tasks are unrealisable. The destiny of Man – his privilege and honour – is never to achieve what he proposes, and to remain merely an intention, a living utopia. He is always marching towards failure, and even before entering the fray he already carries a wound in his temple. This is what occurs whenever we engage in that modest occupation called translating.3

What Ortega y Gasset articulates in the above passage is the perceived frustration of the poetry translator, who must engage in a constant comparative tug-of-war between the original text and his own, forever inferior creation. Such attitudes are grounded in one’s general approach to translation, which all too often involves an inordinate reverence for the original text and an inevitable disdain for the derivative creations of the translator. Indeed, the view of translation (and of translators themselves) as subservient and subsidiary has plagued translation commentary for centuries. Feminist translation theorists have played a pivotal role in exposing and critiquing such perceptions. Sherry Simon, for example, argued that both translation and women have historically been branded as the weaker figures in their respective hierarchies, resulting in an enduring ‘heritage of double inferiority.’ This heritage abides in contemporary translation commentary, as evidenced by a persistent tradition of harsh translation criticism and the self-effacing, apologetic tone that continues to haunt many a translator’s preface.

Translators themselves know that the rhetoric and symbolism around their craft, both age-old and contemporary (the erasure of translators, for instance, is still present in a surprising number of literary reviews and paratexts) is inadequate. It fails because it fails to see what translation actually is: not the crass plucking of a flower but a re-arrangement, a re-contextualisation. A re-birth, even.

If little is said, these days, about poetry, then even less is said about the translation of poetry. A more topical arena for the same discussion is the question of machine translation. The shared soil between poetry and AI may not be immediately obvious, but arguments around both are rooted in the same (astoundingly common) misconception: that translation is a mechanical act, not a creative one.

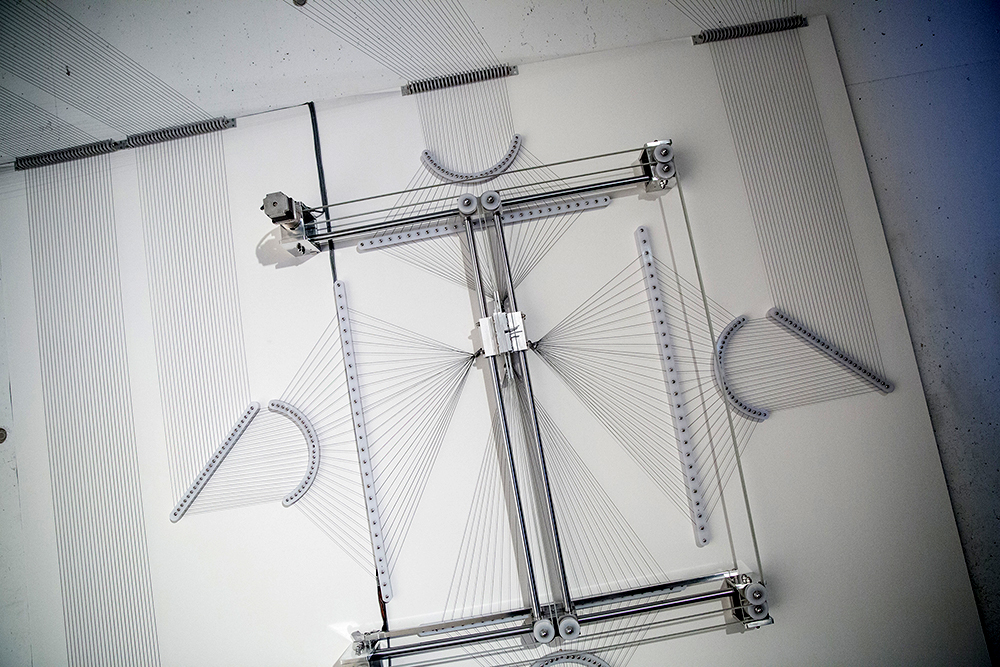

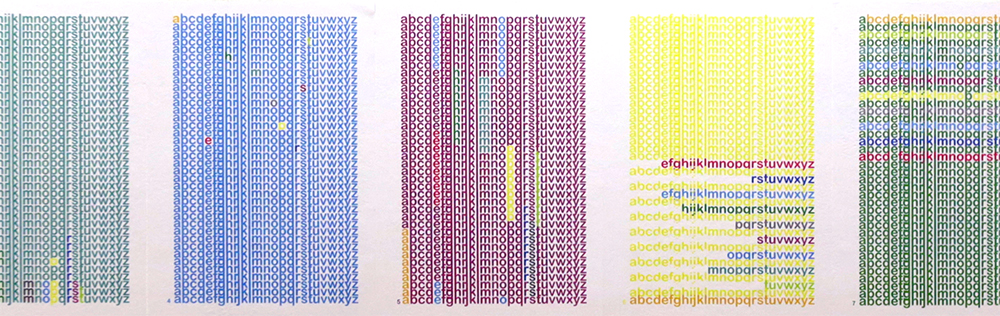

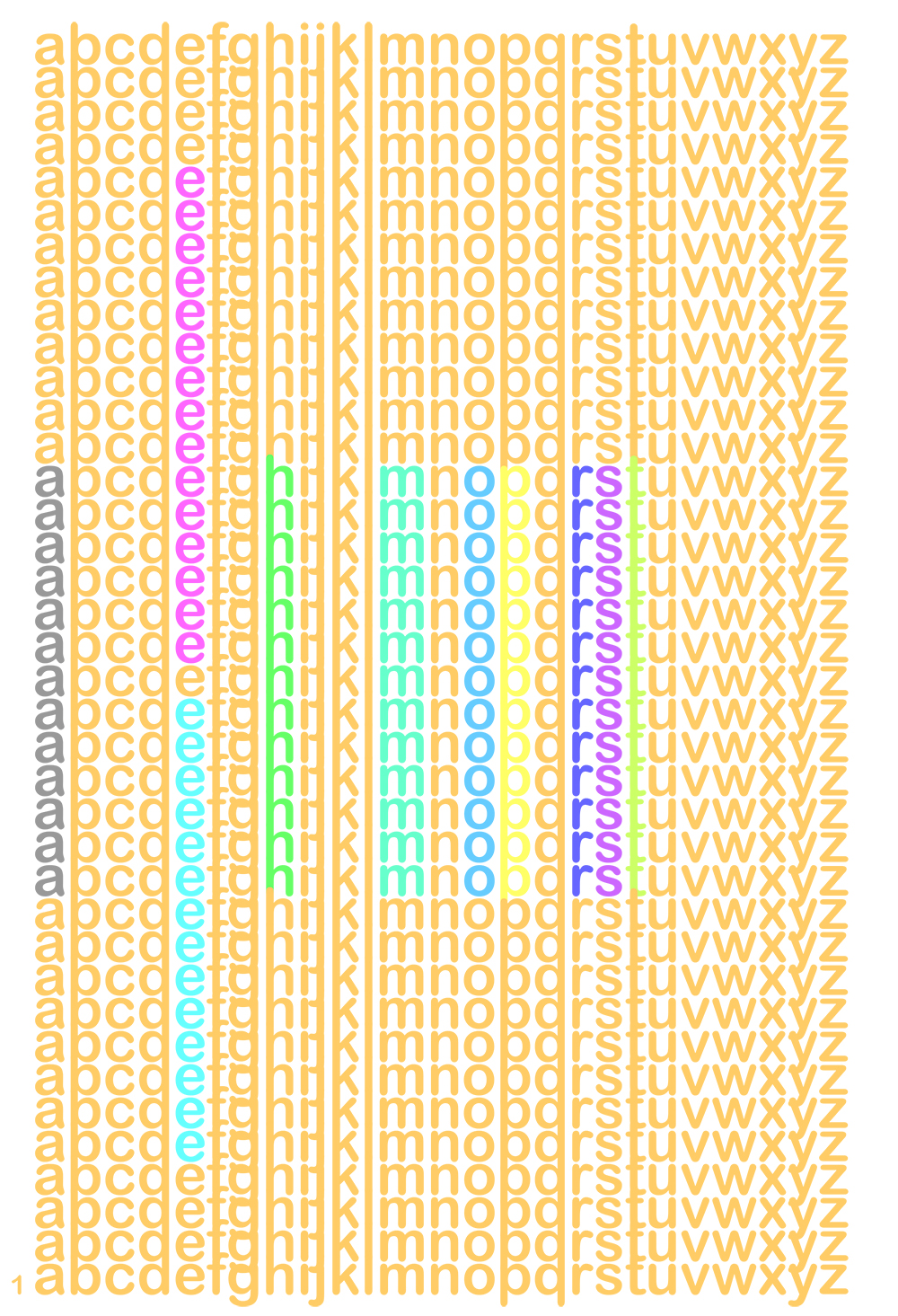

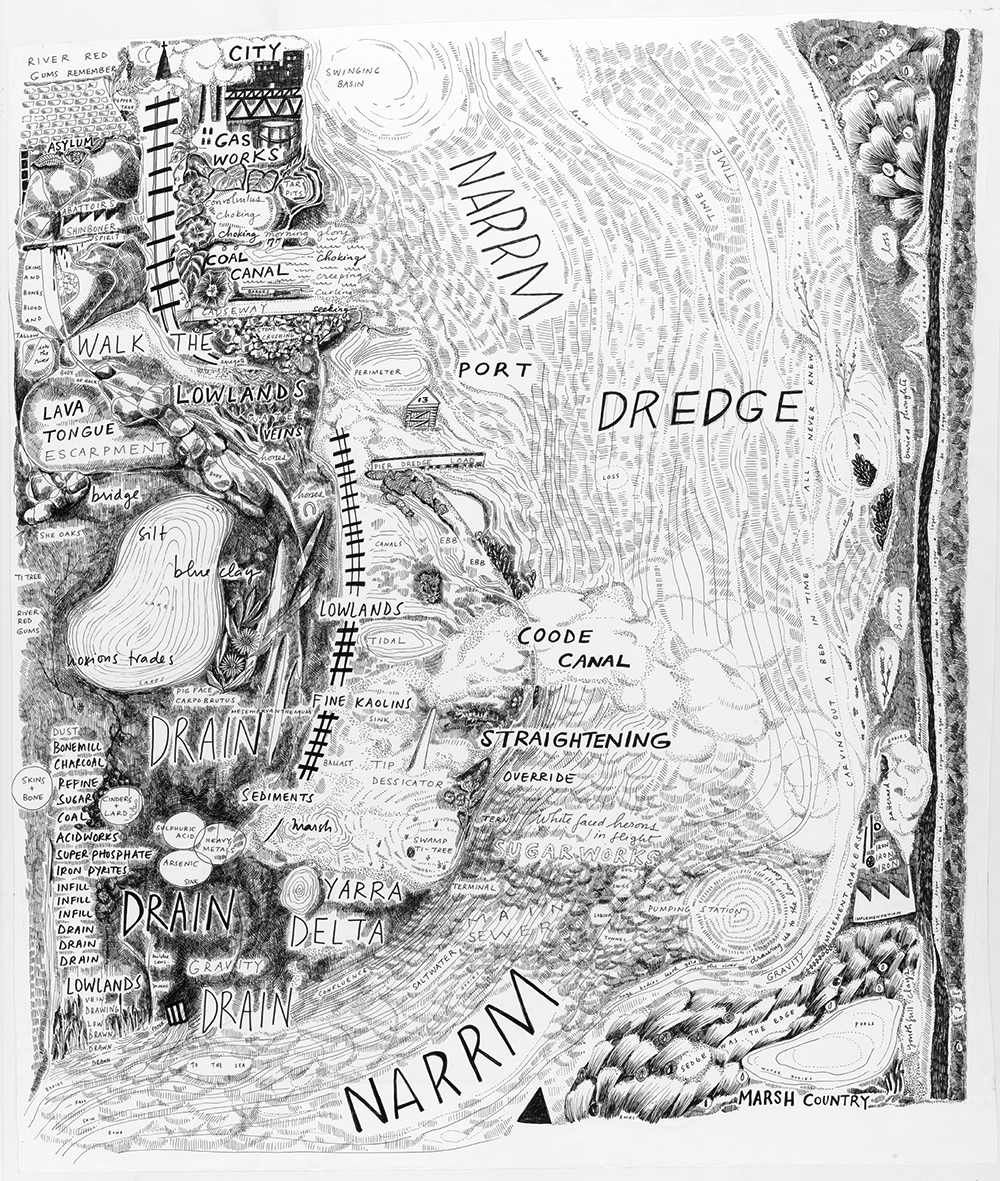

Image courtesy of the author

Image courtesy of the author