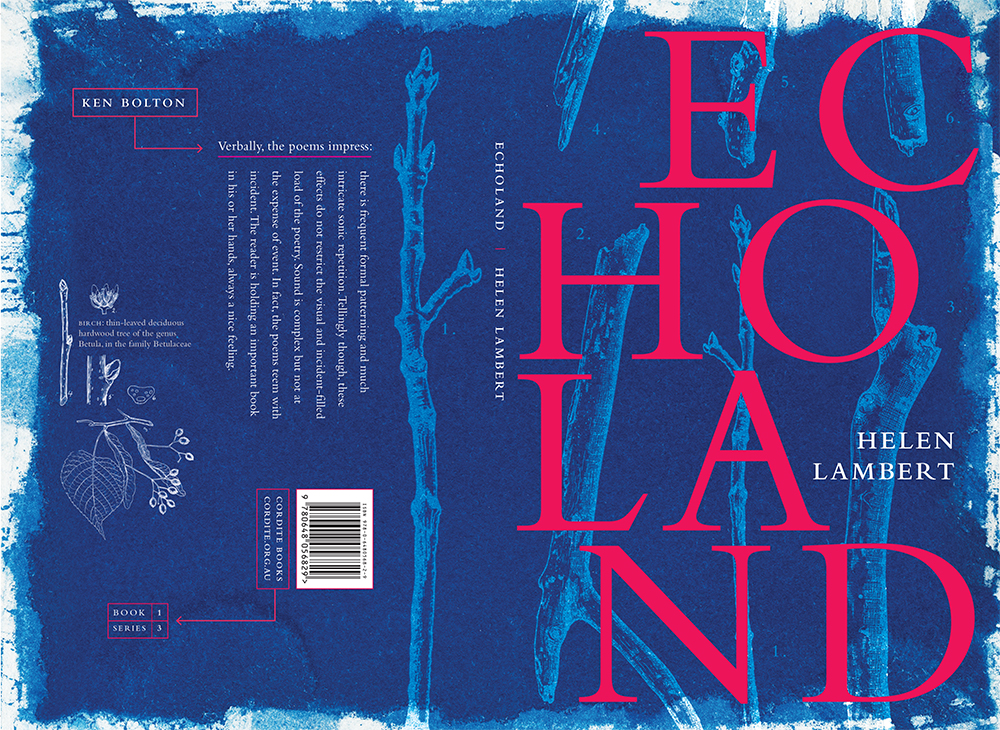

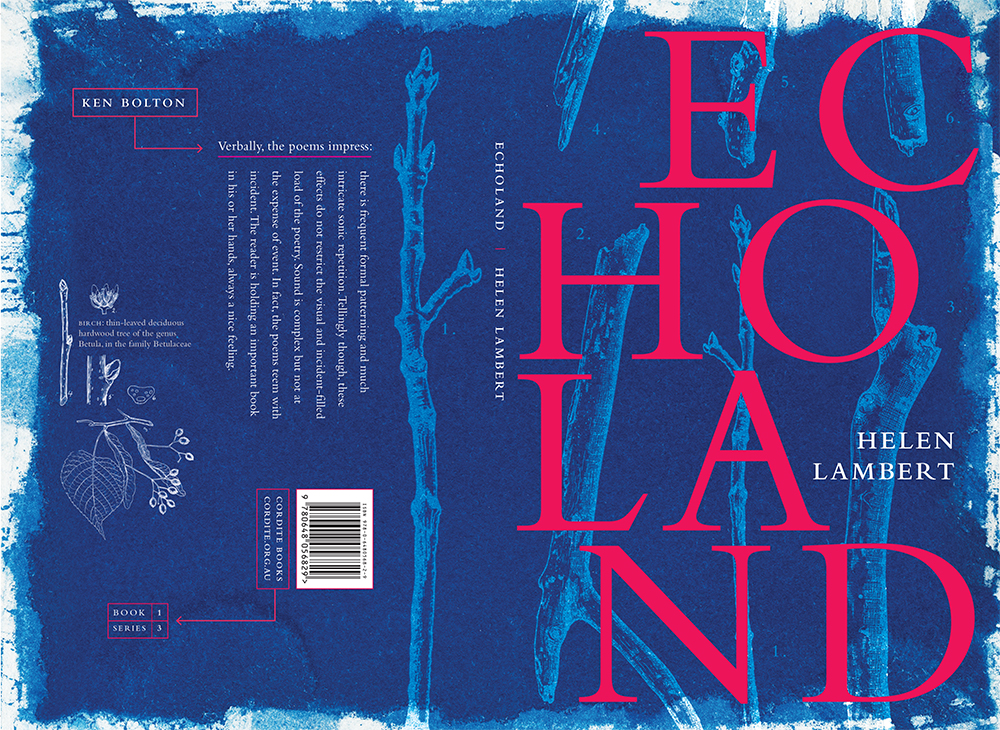

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

BUY YOUR COPY HERE

Helen Lambert’s work is as new to me as it will be to others – she has been operating away from Australian poetry for some time, with long periods in Ireland and, lately, Russia. One approaches a new poet warily. Yet the inventive and capable intelligence behind the poems here is immediately apparent. It is wonderful to be able to drop one’s guard, to forget it – and to enter a wonderful world. From the opening sequence Echoland is imaginatively and aesthetically gripping.

Lambert marshals sharply realised images, and scenes, and atmospheres – and strongly put positions, or logic of argument and implication. The worlds conjured often seem like paintings – hard, firm, immobile – or like stills from films, and a little wintry, perhaps because so often they are the fir and birch forests of northern Europe. Furthermore, these scenes can seem miniaturised. The result – desired, we are sure – a tilt towards the Gothic, the folk tale and fairytale and, sometimes, horror. It brings a degree of distance, if not exactly detachment, of artifice: this is not the casual eye of the subject-viewer giving description, but an authoritative, narrating inventor’s overview. Do we tend to look down from above in these poems? Myths, tales, are made over, re-told. ‘Echo and Narcissus’, for one.

‘Roger, Roger, Roger, Roger, Roger’ is the Kafkaesque presentation of the boy – dead? missing? – replaced in his family, replaced at the family table, by the dog. The dog, we figure, has been given the speaker’s name, ‘Roger’. We know this from his brother’s regular complaint – ‘you called him Roger’. Nor, of course, can the aghast but more or less invisible speaker, who recalls – though the poem’s demotic is Angela Carter’s – Kafka’s Gregor Samsa.

But I should not compress Lambert’s range: these tendencies are neither uniformly present nor in equal strengths throughout. The poet does not – or not ostensibly – speak in her own voice but through personas, or via ‘voices’, that are believable, but which exist for us to try on, to live through. The writing is clear-eyed, and yet, in some instances feel as a dared dream or imagining – a testing of likely outcomes: what will happen to me, will this happen to me? Fraught envisionings. But there is more going on, more to be said.

Verbally, the poems impress: there is frequent formal patterning and much intricate sonic repetition. Tellingly though, these effects do not restrict the visual and incident-filled load of the poetry. Sound is complex but not at the expense of event. In fact, the poems teem with incident. Events, details, are held, fixed: the distancing, the artifice and control of the poet as narrator and picture-maker. The reader does not have to like pictures – Vivienne Shark LeWitt, Elizabeth Peyton, Tarkovsky, Brueghel – to like these poems. It would pay to like poetry.

In the mix are Beckett and Irish speech patterns – spiralling, reiterative loops – and the Baudelaire of the prose-poem vignettes, the Frenchman’s eye for detail that presages a coming modernity and foreshadows change in values and behaviour, though Lambert’s vision is contemporary. A moralist then? Not essentially so, but prepared on our behalf to inhabit that space as we eye our troubling, looming future.

The collection closes with a parodic pastoral dialogue featuring, as the male swain, Donald Trump – has any statesperson’s speech proposed the magical the way Trump’s does? The argot is teen girl, camp, and with an admixture of male, bar-room finality for closure. In ‘Trump’s Bone’ Lambert plays his enchanted world view off against a Russian female agent’s language of real-politik. Lambert’s feel for his idiom – and her sensitivity to its naivety, its ludicrous lead-with-the-chin vulnerability to attack, vulnerability to fact – creates a theatre for sexual politics, for the drama of ideological assumption and ideological parry and thrust. The reader is holding an important book in his or her hands, always a nice feeling.