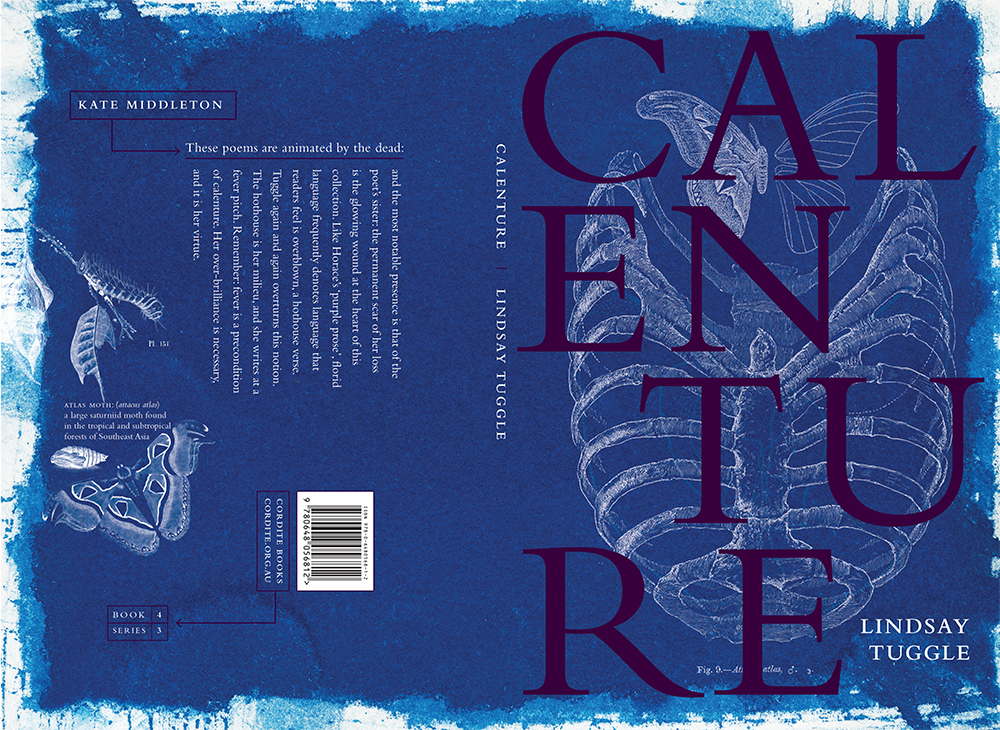

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

Lindsay Tuggle’s poetry is uncomfortable to read: the discomforts one feels in reading her work are the very thing that make it memorable. At once immensely personal, ornate, and unapologetically embedded in female experience, it is a style unconcerned with irony or terseness. It is a verse informed by the still-alive alternative histories of the American South and haunted by the Southern Gothic literature that these histories inform. It is also informed by the Gothic that comes to us from north of the Mason-Dixon Line: a world of autopsies, of madhouses, the weird souvenirs of books bound in human skin.

Tuggle’s is a poetry that emerges from a state of being between. She writes her American experience from Australia: a psychic distance that allows her to look at her subject with a clear eye. As an American, Tuggle observes that Australia is not immune from revisionist histories, and the sense that many among us live in an alternative present. She shows us how to traverse this ground.

The title of this collection refers to a misapprehension of one’s surrounds: the sailor feverishly believes the open sea that surrounds him is solid ground. He jumps overboard, only then learning the truth. The sailor’s experience of calenture is, like Tuggle’s verse, an overlay of an alternative present on immediate terrain. The green land the sailor sees on the surface of the ocean is the mind’s deadly trick in dealing with a no-longer sustainable present moment. Her verse uses elegy as a form of resurrection: that resurrection is a way to more truly unveil what is unsustainable.

Tuggle’s work proposes that we need a poetry of women’s bodies: not solely the female body as object of desire, or the female body as motherly (a vessel already frequently found in poetry both old and new) – but also a poetry of the misuses of the female body, and what occurs between states. Tuggle writes, ‘she’s prettier now / in coffined silhouette’. She writes, ‘The explosion that is my face / always was political’. She writes, ‘We are all flesh / toying architecturally with bone’. Her poetic autopsies go beyond the prettiness of a dead girl’s face, the living girl’s face, and gets into architectures physical, psychic, personal and cultural.

These poems are animated by the dead. The most notable presence is that of the poet’s sister: the permanent scar of her loss is the glowing wound at the heart of this collection. The poems that result from such a wound reflect a state in which the keening necessitated by this loss may never end.

In ‘Asylum, Pagaentry’, the asylum of history disallows the ‘florid stutter’ of the female sufferer, the keener. In contrast, Tuggle’s poetry demands this stutter. ‘Florid’ is a word that is often used to undermine the value of language: like Horace’s ‘purple prose’, florid language frequently denotes language that readers feel is overblown, not commensurate with its subjects. It is a hothouse verse.

Tuggle again and again overturns this notion. The hothouse is her milieu, and she writes at a fever pitch. Remember: fever is a precondition of calenture. Her over-brilliance is necessary, and it is her virtue.