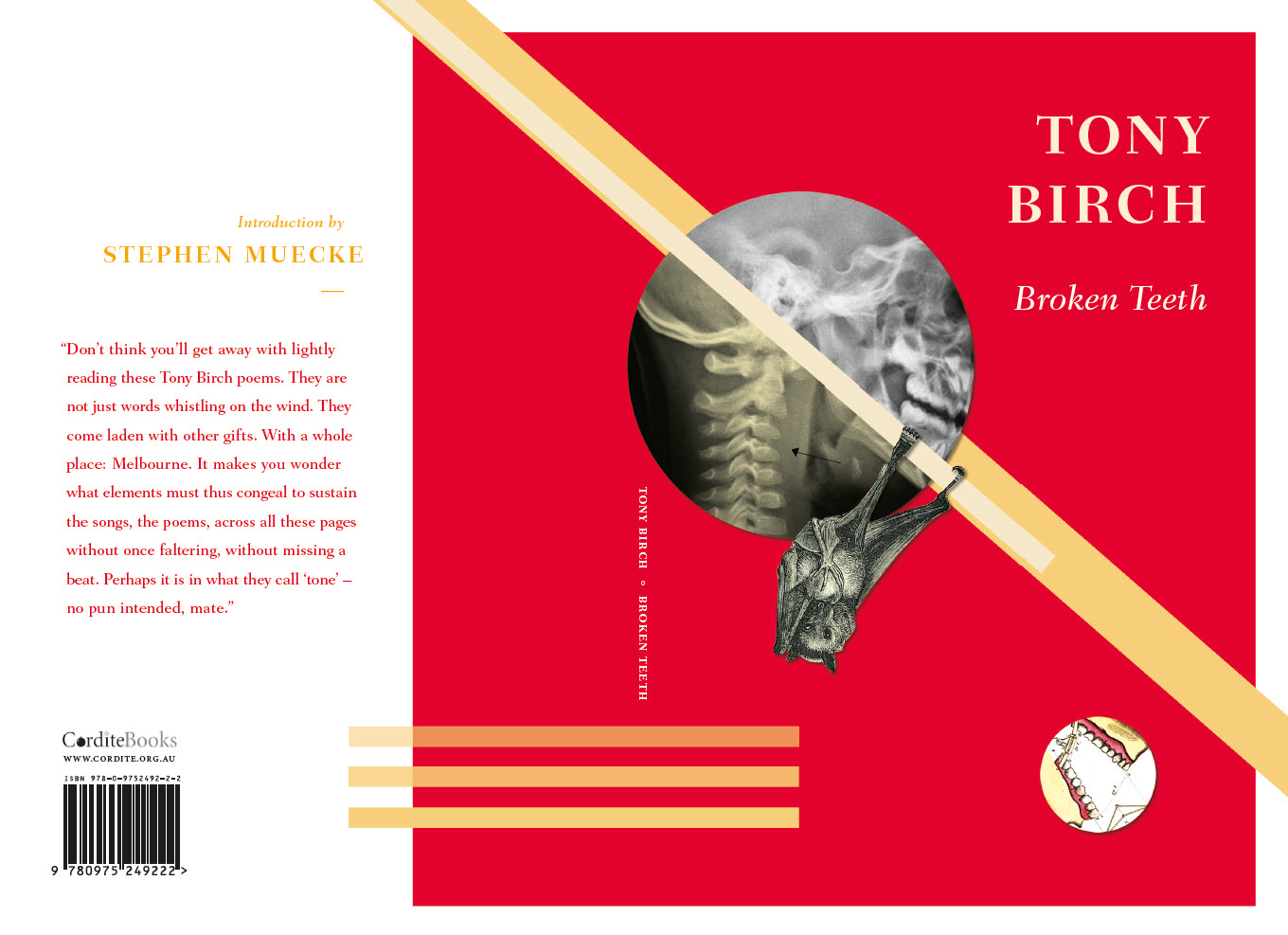

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

Don’t think you’ll get away with lightly reading these Tony Birch poems. They are not just words whistling on the wind. They come laden with other gifts. With a whole place: Melbourne. With a long history: from before the bay filled with water, from after whitefellas came in boats and called it Port Phillip, through to today when others desperately try to reach Australian shores. The refugees’ boats, the poet tells us, are still made from trees that were once earthbound, but stretching upwards. Then, like poems, they are laid down and recomposed for voyaging.

Few writers love their hometown as ardently as Birch. Read his novels and stories, look at his photographs, listen to him tell tall stories about it, run with him along the contours of its creeks, or stroll with him in the Melbourne cemetery to chat with the dead. It makes you long to ‘… rest along the / bluestone gutter…’. That hard, polished bluestone that cobbles the back lanes of Melbourne. They are the half-secret byways where Fitzroy kids can escape, play footy, get up to mischief and hiss a warning about the ‘toe-cutters’.

Sound parochial? Sure, the inner city is Birch’s local run and his knowledge runs deep. But the arc of reference is greater than for many whose compassion is not tested by suffering. You can be inner-city and global at the same time, and refuse the kind of insularity forged by fence-building for property protection. The elegy for our Japanese friend, Minoru Hokari, who jumped the fence between anthropology and history to make a journey with the Gurindji, still makes me want to weep each time I read it. And ‘Michael’, who I didn’t know, and the boat people who no one in Australia knows. They will find a welcome in this poetry that understands how to express sovereignty without border protection.

Birch also delves into another place where things are half-concealed, the documentary archives. They turn up the most poignant letters from earlier days when, for Aboriginal Australians, even moving around was a trial or a life-threatening experience. The pages from the archive are here turned, and once again recomposed. Or ‘The True History of Beruk [William Barak] (archive box no. 3)’ spills the history of William Beruk, and this remarkable text goes on to experiment with lists of objects and with prose.

Objects proliferate in ‘The Anatomy Contraption’ sequence, where, in a singular assemblage of technology, modern science and early- twentieth-century eugenicism it is easy to coolly dissect ‘three infant hearts’ for a cabinet of curiosities, which ‘congeals together / like a song’. It makes you wonder what elements must thus congeal to sustain the songs, the poems, across all these pages without once faltering, without missing a beat. Perhaps it is in what they call ‘tone’ – no pun intended, mate. What is ‘it’? A combination of sounds, feelings and meanings (you can’t afford to sound flippant, insincere or, if sincere, not earnest); it’s such a fine line! The right tone is what makes these poems happy with themselves in this space they now inhabit, hovering between performance and reception. Birch is not immaterial in this composition – he forges it, and gets the tone right by having a felicitous and easy-going relationship with resonant words bearing honest feelings and just thoughts.