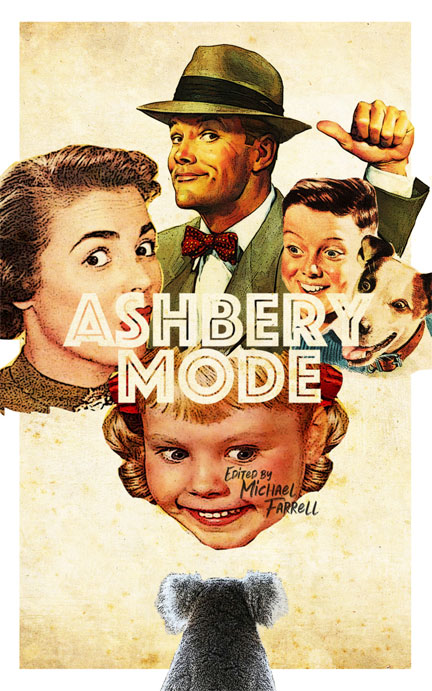

Ashbery Mode

Ashbery Mode

Edited by Michael Farrell

Tinfish Press, 2019

The presence of John Ashbery shines over contemporary literature, for many as an enigma, indisputably as a catalyst. Part of the post-World War II wave of new American poetry, his name is grouped not just alongside his contemporary poets but among their literary schools and movements: the L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E school, the New York School, the San Francisco Renaissance, the Beats, the Black Mountain poets, our own ’68ers and J.A.

With its larrikinism and easy-going feel, even, not paradoxically, but inventively, at its most serious and radically experimental, it’s not hard to see how Ashbery’s poetry has almost always been popular with Australian poets, as much as the poetry of any other international poet. It is fitting then that Michael Farrell, undoubtedly one of Australia’s leading Ashberyians, has put together an anthology of Australian responses to John Ashbery’s poems, published just a few years after Ashbery’s death.

Ashbery Mode is a refreshing and innovative addition to Australian literature and a timely and illuminating opportunity to see how Ashbery’s mode has found expression in Australian poetry across two centuries.

I will first explore that expression by looking at how some of the most successful poems in the anthology adopt some of the most vital aspects of Ashbery’s mode in relation to poetic form, self, society and politics.

Let’s start with Ashbery’s use of the meta-poetic and a strategic metonymy. Ashbery can frequently be found commenting on his poetics within poems, whether cryptically, ironically or more directly. Ashbery’s poetry, like life itself, also presents a plurality of meanings. Often certain meanings are more dominantly implied and made buoyant by background strategies of metonymy. Even so, lines are simultaneously kept open to other interpretations, like music, acting as analogous channelings for any number of experiences or emotions.

Take these lines from the poem ‘Awkward Silence’ by Angela Gardner:

This is the moment to decide what to leave behind, instead

we get biblical, no longer recognisable. Familiar text

spews from what we say is our m. (marginalia) m m.. (marginalised)

m m m...(mouths).

The use of first-person plural invites the reader to position themselves as the poetic personae. In these lines, and the lines preceding, the specific situation has been kept vague. We are forced to lean into the language. Metonymically, with allusion to the creation of text and the ‘awkward silence’ of the title, we are leant into the interpretation that we are sharing the ‘awkward’ composition of the poem. In ‘our’ moment of deciding ‘what to leave behind’ we are taken over by an upsurge of ‘biblical’ but ‘familiar’ text. The narrative voice suddenly stalls and enters a comedic B-grade horror movie death throes, achieved with an A-grade literary acrobatics.

The conflict of composition is revealed as the conflict of self, a perpetual flux of inside and outside worlds.

Craig Hallsworth’s poem ‘Dolors’ begins with a meta-poetic moment which both parodies and hyper-realises the role of influence in poetry:

My mound was effectively to meet a poet

with connections

High up in the food chain – that is awful of me

I must admit In any case I imagine

He would have sat right where you are sitting now

Within the collocation of its line the use of ‘mound’ suggests lot and fate. Within the wider context of the stanza it meta-poetically suggests oeuvre. The authority or sanctimony of a poet’s status or voice is playfully diminished. The personae then bitingly presents poetry as a consumerist hierarchy before opening the fourth wall to bemoan the espousal.

Like in Ashbery’s poems ‘Rain’ or ‘Europe’ from The Tennis Court Oath, the scattered form of the poem presents the poem as process rather than product, as mental-activity concurrent with the page. All pronouns dissolve into the poem’s planar treacle ego and the space of the poem becomes an all-encompassing meeting place, integrative rather than imposing:

But then ask yourself

What am I not

A turgid member of Am I not every bit

As embrangled in these fatal paraphernalia Have I not

Myself on occasion found it rather cosy All of us

Ghouls together

In a hyper-connected world where connection is often superficial and information is often torrential Hallsworth’s, following Ashbery’s, embodiment of a collective societal identity amounts to a radical democratic maneuver which constitutes ‘a commitment to democratic communication which is a challenge to, not a legitimization of, a society which makes it increasingly difficult’ (Herd 10).

In Ashbery’s poetry discursive tones and registers are blurred and mashed. The oversaturated and constellated nature of our discursive world is simultaneously illuminated and leveled out.

Take the following lines from a section of stanza two and eleven of Toby Fitch’s ‘All the Skies Above Girls on the Run,’ a collage poem assembled with parts of lines that reference the sky in Ashbery’s book-length poem Girls on the Run:

in the comet of the lighthouses

plastic star removal continues the real message

being written in big air bubbles

how serious we are as we dance in the lightning of your rhythm

like demented souls did we outwit you

The odd collocation of ‘the comet of the lighthouses’ echoes titles of American westerns and country songs such as Riders of the Purple Sage and ‘The Coward of the County’, the collocation of ‘plastic star removal’ echoes an advertised service such as ‘chipped paint removal’ and ‘written in big air bubbles’ sounds like the simplistic awe of a child. Shift to the next stanza and we have two lines that are more uniform in register and tone, presented with a verbose Elizabethan syntax.

In Girls on the Run this intricate tapestry of tone and register, aside from being delightful, presents the complex time-warp of the present in which the innocent girls must build and position their own identities, buffeted by a barrage of pre-existing positionalities and contexts. Fitch’s collage poem distills, rearranges and crystallises this effect.

The poem ‘Cloud Cover’ by Julie Chevalier exemplifies what John Koethe has called Ashbery’s ‘metaphysical subject,’ in which the subject or personae of the poem is refracted and dispersed, ‘yield[ing] only a personality or image that is ‘other’…timeless’ and knowable only as fragmented ‘surface’ (Koethe 92). Chevalier presents us with a series of floating images:

a cloudboat becalmed

a ghost ship sipping iced tea floating islands in a lemon sea

waves rolling in like mountains breaking iceberg floes ice blocks

a monolithic baldie a dancer a twister i couldn’t resist’ er

chicago daily trib clouds buck rogers clouds in the 25th century

The images and syntax appear like incomplete mental representations of an unmediated self, directly confronting the reader. The images crackle with personality. Associational sonic jumps like ‘iceberg floes’ to ‘ice blocks’ and the surrealistic, jumbled and retro subject matter give the impression of a daydreaming mind in scatter-thought. What is brought into relief here is the sheer magnitude of mind and identity.

Ask Me About the Future by Rebecca Jessen

Ask Me About the Future by Rebecca Jessen Ashbery Mode

Ashbery Mode