Dark Matters by Susan Hawthorn

Spinifex Press, 2017

Where, as Jovette Marchessault asks, is the Tomb of the Unknown Lesbian?

Susan Hawthorn’s Dark Matters is a culmination of over thirty years’ lesbian feminist activism and fifteen years’ research focused on violence – specifically torture – against lesbians in a global context. Hawthorn’s embodied experience and creative-intellectual rigour bring politics and poetics, desires and denials, silences and protests, bodies and implements of torture, intimate meditations and research expeditions, productive rage, testimony, speculative fiction and ficto-criticism together in a single novel.

The novel is framed in ficto-critical terms as a creative writing research project called Diagonal Genealogies. It is a project that examines ‘the ways in which women passed down memorabilia through their families, particularly looking at women who do not have children.’ Desi, the writer-researcher, has inherited boxes of writings by her aunty Kate (Ekaterina). On the verge of ‘junking the lot’, Desi sits down to read what the boxes contain. In them she discovers writings that document, in fragments and with enormous gaps, the abduction and torture of Kate and the attempted assassination of Kate’s lover, Mercedes.

From the decayed fragments of Sappho (Psappha) to the works of HD, Monique Wittig, Anne Carson and Marion May Campbell, fragmentation has been developed as a deeply political and poetically significant way to write stories of how lesbians live and die. The importance of fragmentation for writing lesbian stories derives from diverse, but entangled, situations: 1) the under privileging and active silencing of lesbian stories, cultures, histories and identities; and, 2) the activist practice of turning sites of oppressive silence into zones of speech and creativity.

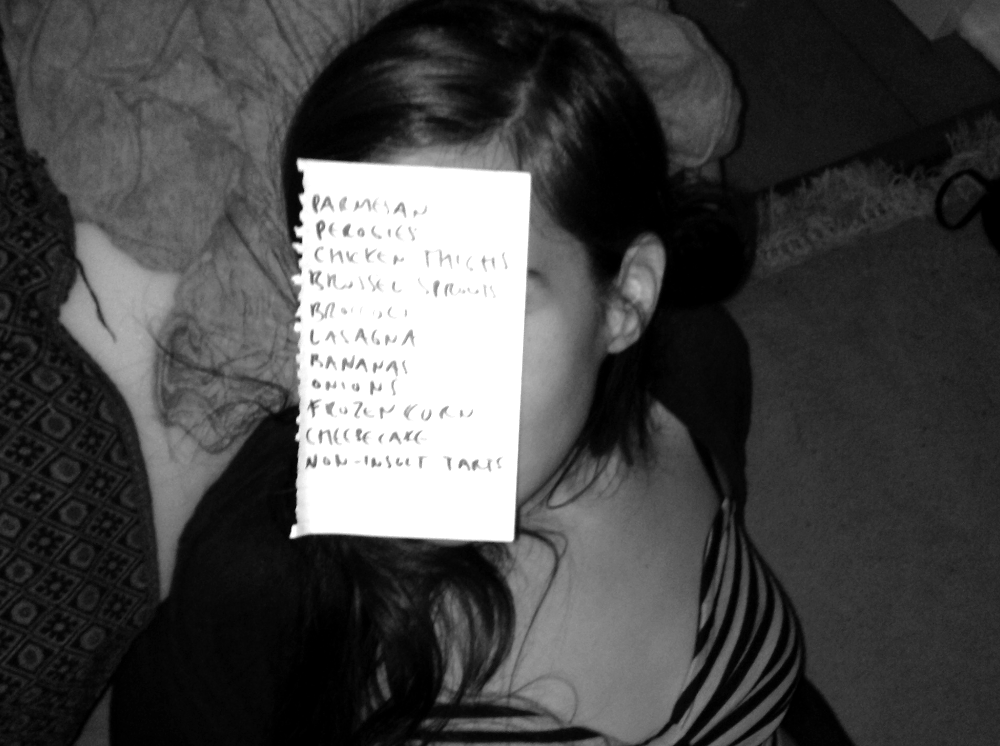

Denial of stories is an agile way to nullify histories and identities. Desi discovers that lesbian lives are not something that can just be researched, they must be investigated because the gaps in the official, and unofficial, archives are enormous. She puts it like this,

That’s the thing about lesbians, it’s a kind of detective story that unwinds in scraps but half of the pages are shredded and the rest are so destroyed as to be unreadable.

Drawing on this history of poetic fragmentation, Hawthorn produces a generically hybrid and polyvocal novel with interloping stories of missing girls, abducted and assassinated women, silenced mothers, institutionalised aunties, as well as the abandoned and profaned monsters and goddesses of ancient myth. In Dark Matters these fragmented narratives cross over and into each other’s stories; they begin to read as a live archive of lesbian histories. In this novel, Hawthorn shows that the stories of women who refuse to live by the confining codes of heteropatriarchy can be entered through the portal of countless names which are not often spoken of within the dominant cultural scene: Vera Rubin, Demeter and Persephone, Baubo, Ekhidna, Sappho, Hecate, dyke, Monique Wittig, HD, Virginia Woolf …

While fragmentation as a writing strategy has often been theorised in relation to the white space of the page that surrounds it, Hawthorn situates her fragments in relation to dark matter. It was the American astronomer Vera Rubin who proved, in Western techno-scientific terms, that dark matter constitutes most of the mass that exists in the visible universe. Furthermore, Rubin showed that dark matter binds visible matter. Hawthorn activates dark matter as a potent poetic trope in Dark Matters. It is a trope that allows Desi to think through the invisibilisation of lesbian lives and deaths in social, cultural and political domains. ‘Imperceptibility’, Desi writes, ‘is not a clue to non-existence, as Vera Rubin discovered.’

So much can be discovered in silences, deletions and detectable absences. Each fragment in Dark Matters maps into histories and imaginaries that are carved out of gendered and sexualised violence. Violence in Dark Matters is considered on physical, conceptual and representational levels. Hawthorn is acutely attuned to the way the animalisation (or dehumanisation) of lesbian lives, loves and acts work as a conceptual violence that paves the way for physical violence. When Kate is first locked in isolation she is hit by smells,

… the smell of animal urine mixed with fear

… the smell of an abattoir or of a place where animals are slaughtered.

I shake and I sprout feathers. I take off and soar: a wedge-tailed eagle. I leave this horror behind.

For her torturers, Kate-as-lesbian makes Kate an animal. But Kate finds life in animal identifications. Reflecting on Kate’s writings, Desi notes,

She describes a range of animals from a lesbian-centric point of view. She is creating a universe in which lesbian symbols lie at the centre.

In isolation and after torture sessions, Kate tells herself stories about animals. She recounts animal visions from myth, she dreams-up narratives of other women who gather around her, who become her animal familiars. Dropping in and out of sensibility, and to escape the reality of torture, Kate becomes a myriad of animals:

I’m a wolf, loping (louping) through the forest.

My arms are growing wings. Wings of heavy metal. Collapsing wings. Too heavy like the wings of the Hercules moth …

… colourful fish swim by like a pack of women. Others travel singly or in pairs. Their sides, rainbow-streaked. Parrot fish. I am floating free in this tropical water. I am swimming back forth and around, over the bommies. Mushroom and brain coral dot the shallow sea floor.

In Kate’s lesbian imaginary, there is hope in multiplicity, in mutability, in stories about bodies that come undone and become-other.

Nowhere in this novel does Hawthorn seek to resolve the political and literary erasure of lesbian lives and deaths, but every page of this novel works to make those erasures visible. It might only take hours to read Dark Matters, because it is so often paced like a thriller or detective novel. But it will take many more hours, weeks or months to reckon (really reckon) with the myriad intertextual citations Hawthorn includes; all of which offer storied paths that lead toward ever more stories that track through the hidden lives and deaths of lesbians.

This is a book of underworlds and infernos, places of execution, practices of erasure and sites of desire. It documents the practicalities of attempting to break lesbian cultures woman by woman, finger by finger and story by story. Against such violence Hawthorn offers poetry as activism, as remedy, as mode of repair.

Dark Matters is a meteoroid. When it hits, it will make a different world of you.

Image by Nicholas Walton-Healey

Image by Nicholas Walton-Healey