children the size of adults

pester me with questions like

how big is your carbon footprint?

I mean yes

I’m a minor poet

not a major corporation

but I’d still prefer being

taken to task by someone

with a stake in the future

over being taken to court

watching the lawyers

stride in

& out of the stone building

from the shade of this

frankly arrogant tree

resplendent with carbon

there is a whiff of the

entitlement that comes off

a certain kind of person

who when asked

still or sparkling

answers

sparkling

or

something equally

as bougie

—is firing off tweets

as bad as burning down

forests?

I mean

I get it

some kids don’t want to have to

think about the anthropocene

they want gazelles

jordans

they want supreme

I

on the other hand

grew up

climbing trees

barefoot & in rags

swinging off

the fig trees

outside the zoo

a real Mowgli figure

of inner suburban Adelaide

imagining the tree

was my mother

or at least the female

tree-character from

Pocahontas

(…Grandmother Willow, but I had to IMDb it)

when

you stop to think

for a minute

that’s a strange film

I mean

from a contemporary perspective

there’s settlement

& the reek of entitlement

not to mention

the extensive

land clearing

plus it stars

Mel Gibson

before he got cancelled

for saying those

awful things about

Jewish people

—my point being

can the market

really be relied upon

to even all of this out?

to absorb our

stupidity

the way trees

absorb our carbon

from the

atmosphere?

can a pouch of tobacco

costing $36

really stop someone

from smoking?

can e-cigarettes?

can this 36 degree day

lived here

that could be anywhere

somewhere in

the golden age of capitalism?

golden

in the way that

a plant turns golden when the sun

had voided it

of its moisture?

golden

in the way

we tend

to convince ourselves

things are beautiful

even as they’re

dying

right in front

of our eyes?

I’ve been

having better conversations

since accepting this

perennial state of

emergency

reading about the school

protests & watching Greta

Thunberg videos on youtube

accepting the

solution will not be simple

or easy

as unpalatable

as it tastes

this soy latte

is not the solution

with the newspaper

in front of me

which I’m sure

almost no one my age

or younger

is reading

the editorial suggests

maybe plant a tree?

or get a sodastream?

failing that

their logic would

advocate

just go back to work

as normal?

& if you don’t have a job

buy one?

between wind and water (in a vulnerable place) by berni m janssen

between wind and water (in a vulnerable place) by berni m janssen

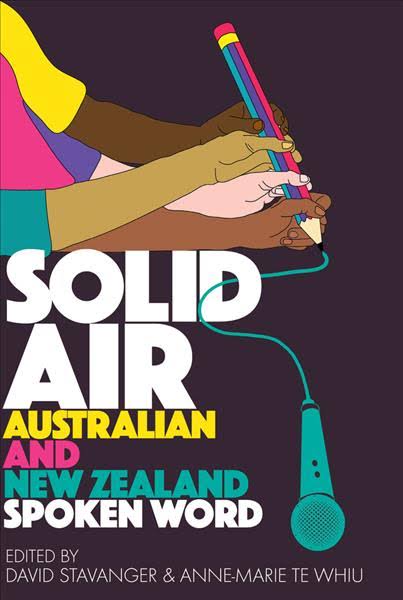

Solid Air: Australian and New Zealand Spoken Word

Solid Air: Australian and New Zealand Spoken Word

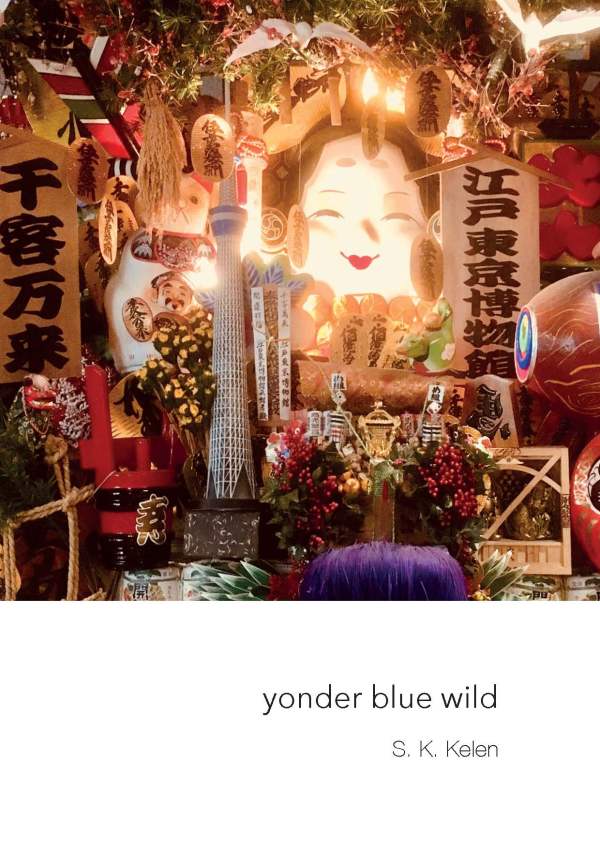

Yonder Blue Wild by S K Kelen

Yonder Blue Wild by S K Kelen