Miro Bilbrough’s memoir, In the time of the Manaroans, is set in a remote countercultural milieu in Aotearoa in the late seventies. At 14, Bilbrough fell out with the communist grandmother who had raised her since she was seven, and was sent to live with her father and his rural-hippy friends. Isolated in rural poverty, the lives of Miro and her father and sister were radically enhanced by the Manaroans – charismatic hippies who used their house as a crash pad on journeys to and from a commune in a remote corner of the Marlborough Sounds. Arriving by power of thumb, horseback and hooped canvas caravan, John of Saratoga, Eddie Fox, Sylvie and company set about rearranging the lives and consciousness of the blasted family unit. – Joan Fleming

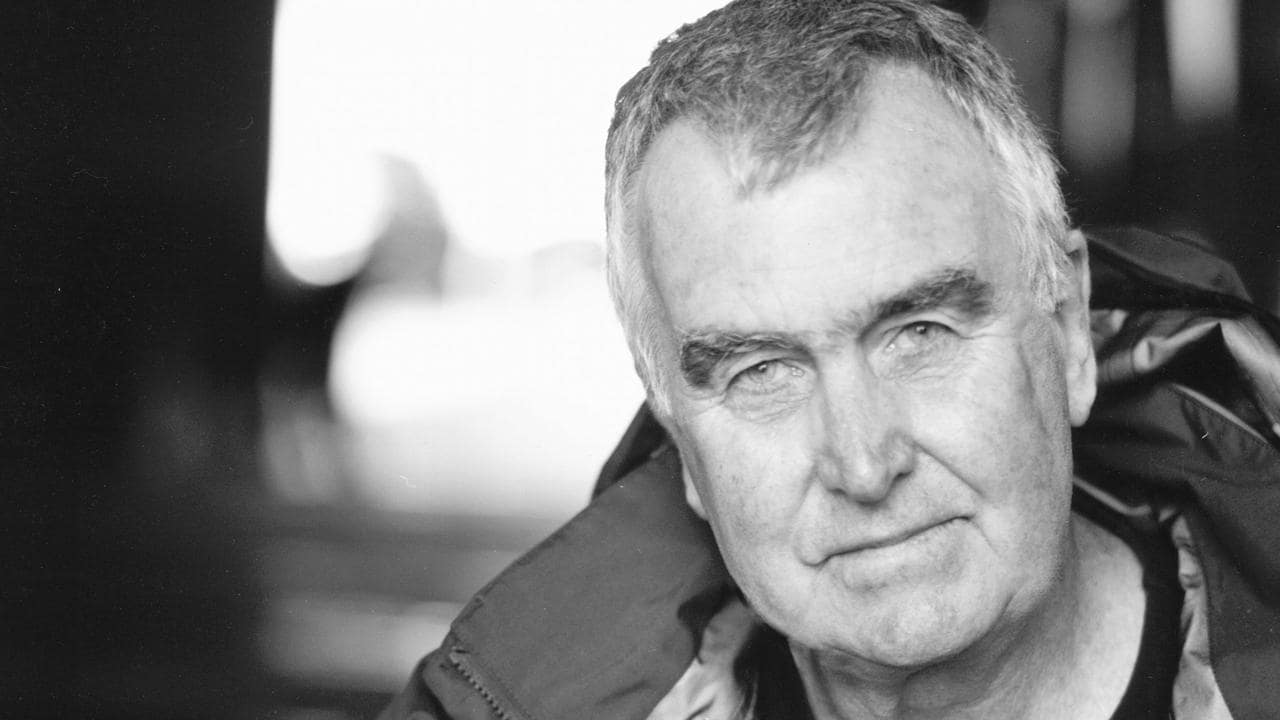

John of Saratoga

Returning from school one dusk I find John of Saratoga cleaving to the ancient rolled sofa arm, ankles crossed, the soles of his long feet black with road filth. The stranger’s gaunt physique draws what light makes it through the clouds of smoke that billow from the wood range as my father rattles its chimerical damper and curses. He is preparing a combination of the usual soya bean omelette and garlicky salad, and fresh peppermint tea in a heavy-spouted teapot. Potatoes, sliced into rounds in the cast iron frying pan, are doused with cream and dusted with paprika before being shoved in the oven in honour of the visitor. My sister has taken the opposing arm and is reading The Blue Fairy Book. Coming through the door I am magnetised by the dark-hued human buoy bobbing up the other end of our unstable sofa.

I quickly establish that John of Saratoga doesn’t speak much but comes to warm himself in my father’s sooty kitchen where the most recent flood-line stains the timber interior a metre up the wall, his utterance upstaged in equal parts by extreme diffidence, an ever-ready irony that operates at his own expense, and a hacking cough. From what I can tell, he is a wanderer seeking the next crash pad, the next hospitably expiring couch whose subsidence draws polite New Zealand bodies towards the vertiginous ditch in its centre. He favours broken-down Salvation Army coats, which enhance his concavity; is dark-haired, nicotine-fingered and carries a dog-eared physics text in his coat pocket. Everything about him tea- and tar-coloured, right down to his teeth, he is like a deteriorated relation of my first love, Cold Tea & Coat.

Mundane biographical details are disdained in the hippy world, direct questions frowned on. When, in Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper insistently asks a fellow traveller where he is from, and is just as insistently deflected, self-conscious credo is elevated to taboo. From my father, who thinks Easy Rider macho and silly, I learn that John’s medieval-sounding nickname is derived from a tiny fishing settlement deep in the Pelorus Sound, where he is based, and that in a former life he was an engineer who migrated from Darwin.

I learn from Dee, from whom my father subleases the Floodhouse, that John of Saratoga periodically goes missing from the hippy circuit. Then, more often than not, his breathing situation will have reached crisis and he is, eventually, to be found in intensive care. Despite being acutely asthmatic, he is known to sleep in a damp swag by the side of the road. That is the sum of available facts. Whoever wrote that romance thrives on an economy of scarcity might have been thinking of Saratoga John.

Despite my school uniform, white socks at half-mast and puppy fat, I have a taste for suffering and a disdain for lifestyle. A chronic asthmatic smoking himself to death, how stylish. My eschewal of the lifestyle category is fortunate because my father’s dump is off the dilapidation chart. The kitchen doesn’t even sport a tea towel, just a stub of bath towel ingrained with stove grime.

Although she is in the process of setting up house with her lover, Dee maintains the best room in the Floodhouse as hers, visiting it but rarely. This is the light-flooded front room in which I camp on first arrival before reluctantly moving across the hall to its darker sister. Originally, my father and this statuesque potter with serious drapes of gold hair thought they might build a kiln together and share firings. They soon revealed themselves ill suited: Dee accustomed to homage; my father disinclined to render. When their collaboration failed to take my father ended up sub-leasing the house instead.

In Dee’s room I can lie in bed and see chinks of cornflower-blue sky or occasionally a star between the wide unlined boards of the walls. Here and there tufts of rose-trellised wallpaper cling like relics of a more couth former life. Blue perforations and chilling draughts acclimatised to, the room is a space in which to brood on the unexpounded facts of my new life, of which there are many.

Sometimes John of Saratoga honours us with a solo visit. Sometimes he turns up in a small party of the Manaroans, commune-dwellers from the remote Pelorus Sound. Once, John of Saratoga arrives accompanied by Eddie Fox, a flashily handsome Welshman, both mounted on Lenny the Horse. My father dreads – and embraces – every option. Fuck. Visitors! And he’s off in a spin about the catering. More mouths to feed! What will the horse eat, fuckit? On the subject of John my father pronounces, with depressive savour, He’s just waiting for death to come along and knock him on the head.

Personally, I think John of Saratoga looks like a woodcut, or one of those linocuts that are a feature of school curriculum art in the sixties and seventies – only made with graver intent. Hacked out by trowel, ink in deep-cut grooves, graven. It is clear to me that none of it would come together without the cheekbones.

His visits, in reality few and far from forthcoming, are enlarged by my inner saucer-eye, my teen-sorcerer eye. I attribute the magic to John of Saratoga, of course. And I am half right. He is a beautiful riddle modestly stalking the highways of our island. It helps that in my father’s house I am inoculated against boys my own age, barely exposed – unless you count the shy, bombastic clods on the school bus, which I don’t.