꽃이 지고

누운 꽃은 말이 없고

딱 한 마리 멧새가

몸을 튕겨가는 딱 그만한 천지

하늘 겹겹 분분하다

낮눈처럼 그렇게

꽃이 눕고

누운 꽃이

일생에 단 한 번

자기의 밑을 올려다본다.

꽃이 지고

누운 꽃은 말이 없고

딱 한 마리 멧새가

몸을 튕겨가는 딱 그만한 천지

하늘 겹겹 분분하다

낮눈처럼 그렇게

꽃이 눕고

누운 꽃이

일생에 단 한 번

자기의 밑을 올려다본다.

죽은 이는 죽었으나 산 이는 또 살았으므로

불을 피운다 동짓달 한복판

잔가지는 빨리 붙어 잠깐 불타고

굵은 것은 오래 타지만 늦게 붙는다

마른 잎들은 여럿이 모여 화르르 타오르고

큰 나무는 외로이 혼자서 탄다

묵묵히 솟아오른 봉분

가슴에 박힌 못만 같아서

서성거리고 서성거리고 그러나

다만 서성거릴 뿐

불 꺼진 뒤의 새삼스런 허전함이여

용서하라

빈 호주머니만 자꾸 뒤지는 것을

차가운 땅에 그대를 혼자 묻고

그 곁에서 불을 피우고

그 곁에서 바람에 옷깃 여미고

용서하라

우리만 산을 내려가는 것을

우리만 돌아가는 것을

헌 신문지 같은 옷가지들 벗기고

눅눅한 요 위에 너를 날 것으로 뉘고 내려다본다

생기 잃고 옹이진 손과 발이며

가는 팔다리 갈비뼈 자리들이 지쳐 보이는구나

미안하다

너를 부려 먹이를 얻고

여자를 안아 집을 이루었으나

남은 것은 진땀과 악몽의 길뿐이다

또다시 너를 낯선 땅 후미진 구석에

순한 너를 뉘였으니

어찌하랴

좋은 날도 아주 없지는 않았다만

네 노고의 헐한 삯마저 치를 길 아득하다

차라리 이대로 너를 재워둔 채

가만히 떠날까도 싶어 네게 묻는다

어떤가 몸이여

저녁이 와서 하는 일이란

천지간에 어둠을 깔아 놓는 일

그걸 거두려고 이튿날의 아침 해가 솟아오르기까지

밤은 밤대로 저를 지키려고 사방을 꽉 잠가둔다

여름밤은 너무 짧아 수평선 채 잠그지 못해

두 사내가 빠져나와 한밤의 모래톱에 마주 앉았다

이봐, 할 말이 산더미처럼 쌓였어

부려놓으면 바다가 다 메워질 거야

그럴테지, 사방을 빼곡히 채운 이 어둠 좀 봐

막막해서 도무지 끝 간 데를 몰라

두런거리는 말소리에 겹쳐

밤새도록 철석거리며 파도가 오고

그래서 茫然한 여름밤은 너무 짧다

어느새 아침 해가 솟아

두 사람을 해안선 이쪽저쪽으로 갈라 놓는다

그 경계인듯 파도가

다시 하루를 구기며 허옇게 부서진다

어떤 벌레가 어머니의 회로를 갉아먹었는지

깜박깜박 기억이 헛발을 디딜 때가 잦다

어머니는 지금 망각이라는 골목에 접어드신 것이니

반지수를 이어놓아도

엉뚱한 곳에서 살다 오신 듯 한생이 뒤죽박죽이다

생사의 길 예 있어도 분간할 수 없으니

문득 얕은 꿈에서 깨어난 오늘밤

내 잠도 더는 깊어지지 않겠다

이리저리 뒤척거릴수록 의식만 또렷해져

나밖에 없는 방안에서 무언가 ‘툭’ 떨어지고

누군가 건넌방의 문을 여닫는다. 환청인가?

그러고 보면 너 어느새 부재와도 사귈 나이,

…… 그날 아무리 밀어도 밀려나지 않던 윈도우의 안개

셋이 동승한 차 안에서 한 여자의 흐느낌 섞인 노래 들었으니

한 번도 죽음을 본 일이 없었기에, 죽으면 어떻게 해야 하는지 알지 못했기에, 죽음은 접시 위에서 살아있을 때보다 더 격렬하게 꿈지럭거렸다. 죽으면 꼼짝 않고 있어야 된다는 걸 몰랐기에, 제 힘과 독기를 모두 모아 거친 물굽이처럼 요동쳤다. 어찌나 심각하게 꿈틀거리던지, 자칫하면 죽음이 취소될 수도 있을 것 같았다. 죽음엔 눈과 팔다리가 달려 있지 않았기에, 방향도 없이 앞으로만 기어가다 저희들끼리 마구 엉켰다.

흰 접시는 마치 제가 죽기라도 한 것처럼 동그라미 안에서 빨판들을 물방울처럼 튀기며 거칠게 파도쳤다. 그러나 죽음이 달아나기엔 접시의 반경이 너무 짧았고, 모든 길은 오직 우스꽝스러운 꿈틀거림으로만 열려 있었다. 토막 난 다리와 빨판들은 한 마리의 통일된 죽음이기를 포기하고, 한 도막 한 도막이 독립된 삶이 되어 접시 밖으로 무작정 나가려 했고, 씹는 이빨 틈에 치석처럼 달라붙어 떨어지려 하지 않았다.

씹을 때마다 용수철처럼 경쾌하게 이빨을 튕겨내는 탄력. 꿈틀거림과 짓이겨짐 사이에 살아있는 죽음과 죽어 있는 삶이 샌드위치처럼 겹겹이 층을 이루고 있는 탄력. 한 번에 다 죽지 않고 여러 번 촘촘하게 나누어진 죽음의 푹신푹신한 탄력. 다 짓이겨지고 나도 꿈틀거림의 울림이 여전히 턱관절에 남아있는 탄력. 목 없고 눈 없고 손 없는 죽음이 터무니없이 억울할수록 이빨은 더욱 쫄깃쫄깃한 탄력을 받고 있었다.

회색 양말을 신고 나갔다가 집에 와 벗을 때 보니

색깔이 비슷한 짝짝이 양말이었다.

이젠 아무래도 좋다는 것인가.

비슷하면 무조건 똑같이 읽어버리는 눈.

작은 차이를 일일이 다 헤아려보는 것이 귀찮아

웬만한 것은 모두 하나로 묶어버리는 눈.

무차별하게 뭉뚱그려지는

숫자들 글자들 사람들 풍경들 앞에서

주름으로 웃는 눈.

웃음으로 얼버무리면 마냥 사람 좋아보이는 얼굴.

이젠 아무래도 좋단 말인가.

빨래 바구니에 처박히자마자

저마다 다른 발모양과 색깔과 무늬와 질감을 버리고

빨랫감 하나로 뭉뚱그려지는 양말들

길에누워자는사람들은밤에자신도모르는사이옆으로와서누워자는사람에게

병을옮긴다고한다살을닿고가만히곁에누웠을뿐인데그들은자신도모르는사이

서로병을옮기고병을받으며죽어간다그들은입을다물지못하고잔다

무당은죽어서도무덤을갖지못한다는데살아서미물이었던그들은죽으면더욱

다정을앓아야한다는데자신도모르는사이그들은언제나칼날위가아닌인간위에서

가장위태로워보인다

세장을열고손가락으로죽은새의목구멍을열어본다액에젖은벌레가기어나온다

벌레가몸에묻은어둠을핥는다그건이쪽의어둠이아니어서나는무덤을갖지못한

새들의저녁을생각한다

감자탕집에서땀을뻘뻘흘리며뼈다귀를뜯어먹는데맞은쪽에서도뼈다귀를뜯고있는사람이보인다

이안(內)은우리같군창문밖엔거지하나주머니에두손을넣고이쪽을빤히바라보고있다

이봐거기는우리바깥이라구입을다물지못하고땀을뻘뻘흘리고뼈다귀를핥고빨고뜯고있는데

먼하늘로수송기한대가좆같은굉음을내며중환자처럼실려가고있다자신도모르는사이여기는

입안의초록을모두열어놓고새의입속으로들어가잠드는, 그래 다물고 감자, 감자

저녁에 무릎, 하고

부르면 좋아진다

당신의 무릎, 나무의 무릎, 시간의 무릎

무릎은 몸의 파문이 밖으로 빠져나가지 못하고

살을 맴도는 자리 같은 것이어서

저녁에 무릎을 내려놓으면

천근의 희미한 소용돌이가 몸을 돌고 돌아온다

누군가 내 무릎 위에 잠시 누워 있다가

해골이 된 한 마리 소를 끌어안고 잠든 적도 있다

누군가의 무릎 한쪽을 잊기 위해서도

나는 저녁의 모든 무릎을 향해 눈먼 뼈처럼 바짝 엎드려 있어야 했다

“내가 당신에게서 무릎 하나를 얻어오는 동안 이 생은 가고 없습니다 무릎에 대해서 당신과 내가 하나의 문명을 이야기하기 위해서는 내 몸에서 잊혀질 뻔한 희미함을 살 밖으로 몇 번이고 떠오르게 했다가 이제 그 무릎의 이름을 당신의 무릎 속에서 흐르는 대기로 불러야 하는 것을 압니다 요컨대 무릎이 닳아서 사랑을 하려는 새들은 서로의 몸을 침으로 적셔주며 헝겊 속에서 인간이 됩니다 무릎이 닮아서 안 된다면 이 시간과는 근친이 아닙니다”

2

그의 무릎을 처음 보았을 때

그것은 잊혀진 문명의 반도 같았다

구절역 계단 사이,

검은 멍으로 한 마리의 무릎이 들어와 있었다

바지를 벌리고 빠져나온 무릎은 살 속에서 솟은 섬처럼 보였다

그는 자신의 무릎을 안고 잠들면서

몸이 시간 위에 펼쳐놓은 공간 중 가장 섬세한 파문의 문양을

지상에 드러내 보여주고 있었던 것이다

“당신의 무릎으로 내려오던 그 저녁들은 당신이 무릎 속에 숨긴 마을이라는 것을 압니다 혼자 앉아 모과를 주무르듯 그 마을을 주물러주는 동안 새들은 제 눈을 찌르고 당신의 몸속 무수한 적도(赤道)들을 날아다닙니다 당신의 무릎에 물이 차오르는 동안만 들려옵니다 당신의 무릎을 베고 누운 바람의 귀가 물을 흘리고 있는 소리가”

3

무릎이 멀미를 하며 말을 걸어오는 시간이 되면

사람은 시간의 관절에 대해 이야기할 수 있다고 한다

햇빛 좋은 날

늙은 노모와 무릎을 걷어올리고 마당에 앉아 있어 본다

노모는 내 무릎을 주물러주면서

전화 좀 자주하라며

부모는 기다려 주지 않는다 한다

그 무렵 새들은 자주 가지에 앉아 무릎을 핥고 있었다

그 무릎 속으로 가라앉은 모든 연약함에 대해

나는 이 세상에서 가장 무서운 음절을 답사하고 있었는지 모른다

“당신과 내가 이 세상에서 나눈 무릎의 문명을 무엇이라고 불러야 할까요 생은 시간과의 혈연에 다름 아닐진대 그것은 당신이 무릎을 안고 잠들던 그 위에 내리는 눈 같은 것이 아닐는지 지금은 제 무릎 속에도 눈이 펑펑 내리고 있습니다 나는 무릎의 근친입니다”

서운산 숲 속에 들어왔다 비로소 내 집이다

긴 숨을 내쉬었다

그늘이 그늘 위에 쌓여 있다

가지고 온

몇 줄기 취한 불빛을 놓아주었다 밤이 왔다

어느 나라에서나 자유는 늘 끝에 있었다

백 년의 허접쓰레기들도

하나 둘 놓아주었다

아침에는

빈 거미줄에 이슬들이 대롱거렸다

세상에는 타율이 너무 많았고 상상이 자꾸 줄어들었다

숲 밖의 바람 일부분이

숲 속으로 머리 숙여 들어왔다

때깔나무 잎새들이 지저귄다

돌이켜 보면

오래전부터 나는 문맹자의 자손이었다

어쩌다가

어쩌다가

벗어날 수 없는 교착어의 문자지옥에 갇혀 버렸다s

내생에는 땅속 깊숙이

무슨 나무의 뿌리 한 가지이리라

말 없는 홀어미의 송장과

몇몇 고아의 가마니 덮인 새 송장 아래에서

비가 오다

책상 앞에 앉다

책상이 가만히 말하다

나는 일찍이 꽃이었고 잎이었다 줄기였다

나는 사막 저쪽 오아시스까지 뻗어간

땅속의 긴 뿌리였다

책상 위의 쇠토막이 말하다

나는 달밤에 혼자 울부짖는 늑대의 목젖이었다

비가 그치다

밖으로 나간다

흠뻑 젖은 풀이 나에게 말하다

나는 일찍이 너희들의 희로애락이었다

너희들의 삶이었고 노래였다

너희들의 꿈속이었다

이제 내가 말하다

책상에게

쇠에게

흙에게

나는 일찍이 너였다 너였다 너였다

지금 나는 너이고 너이다

In a book I recently read with my students in an undergraduate translation class, the writer sets forth twenty provocative theses on translation in this era of globalisation for a new comparative literature, ranging from ‘Nothing is translatable’ to ‘Everything is translatable.’1 As for me, translating Korean poetry into English, and vice versa, has always been a very daunting, sometimes impossible, task, beginning in the very point of ‘Nothing is translatable.’ However much time and energy are consumed for translation, I feel my languages, both Korean and English, would never touch the point of ‘Everything is translatable’ but at the same time, I know translation would be the first and final door that I keep going through for comparative literature, for crossing different cultures and worlds. As a translator and critic frequently facing the questions of impossibility of translation such as ‘How can it be possible to translate poetry?,’ I try not to get tempted to give into the fate of translation as transgression, translation as a treacherous activity, keenly aware of the unforgettable moment of fumbling two different languages. To translate poetry, as for me therefore, is to proceed from impossible possibility to possible impossibility and the very force that draws me from the dominant-negative-inevitable potency of translation as transgression or treachery is my humble belief in poetry and literature as living impulse and the yearning for communication in difference. Especially in this era when poetry ‘is beleaguered everywhere,’2 translation would be the very practical space that social and cultural domain of words can flourish again in the experiment and experience, in the absence of real politics of different languages.

Compared to the Western countries where poetry has been marginalized for a very long time, poetry in Korea has constructed a rather happy domain of discourse, taking its existential root in the real history of people, in the politics of everyday life. The overall division between poetry and politics – the one, passive, swoony, not in the business of doing things, and the other, active, gritty, and concerned with reality – does not seem to be applied to the history of Korean poetry. In terms of poetry, Korea has been the real republic of words and the representatives of poets drawn here would prove the wild, wide landscape of contemporary Korean poetry and its vitality. Getting its surviving energy from its unpractical usefulness or useless practice, poetry in Korea has also undergone changes. As noted by various writers, in the Republic of Korea, poetry has long occupied a very active social domain where aesthetic and political aspects of words have been expanded, modulated, experimented altogether. Especially since the 1990s, at once being liberated from the burden of politics or political representation, it has evolved into a more experimental republic of words. The onset of the new poets usually born around in and after 1970s, with their self-reflexive exploration of language and its relation to reality, marks a shift in Korean poetics from what a poem says to how a poem says.

The twenty poets invited here could be examples proving the shift of Korean poetics, almost every one acutely aware of the sociality of poetic language and focusing more on the very moment of poetic utterance in terms of newness. To claim the new, however, is always risky as the new always entails the comparison with the past within the overall ambience of improvement. Avoiding establishing the linear line of improvement, I, in this selection of twenty poets, try to explore a range of modes and directions countering the universal lament that poetry is in crisis. The aesthetic vitality and complexity of Korean poetics is reflected in the poem itself, rather than in the profiles of individual poets. So what I believe in here in this meaningful project as a translator and critic would be the force of language itself, rather than the personal ability of a translator. Passing through the different layers of language, the work is reborn in its new language, as Brother Anthony of Taizé, the most renowned translator of Korean poetry, says in a recent interview:

A poem translated so that it becomes a poem in another language is a different poem, of course. Translation is not anti-poetic as such but the translator of a poem faces multiple challenges. I have often written about the way translated poetry is subject to the same process of “reception” in its new language as any poem originally written in that language. The reputation a poem enjoys in its original language has no significance once it is transplanted into another cultural space; it has to start its career all over again.

When only twenty poets have been chosen from many hundreds, each reader will inevitably find a conspicuous presence of current Korean society, culture, and thinking. At the same time, readers might face conspicuous absences of some other unheard voices, but the absences would in turn form another project to be dreamed or published in the future. Among twenty poets, the names such as Ko Un, Hwang Tong gyu, Lee Si-young, Lee Seong-bok, Ra Hee-duk, and Kim Hyesoon are rather well-known to the English readers as their poetry books or parts of poems are already translated, published, and introduced in English. These poets in the earlier generation, never old in their poetic spirit, show how language brings into play in time and draws the various shadings of beings in this world. The interesting, witty conversation between Buddha, Wonhyo (a Korean monk) and Jesus in Hwang Tong gyu’s poems resonates with a very philosophical thinking blurring the border between life and death. Other philosophical lines in Lee Seong-bok’s poem, ‘Without the Body, Wouldn’t Have Existed’, serenely present the relationship between the body and the sprit, the inevitability of pain in our life, locating the existential questions of being in a most vivid portrayal of landscape.

Kim Myung-in‘s ‘Dating a Jujube Tree’ intensifies the physical proximity of beings in terms of memory. Kim Ki-taek‘s words, focusing on human physicality, articulate the painful and casual relationship of all beings. Park Hyung Jun‘s poems are famous for their beauty of subdued tone, finely grained language and Kim Sa-in‘s meticulous eyes for the lower beings invite readers to touch the heart of every wandering person. Ra Hee-duk and Park Ra Youn‘s poems would be another example of weaving the tradition of Korean lyric voice. In ‘Of Sympathy’, Park seeks to connect the house, a very material territory of a human being, with the soul. In a vivid sounding of everyday activities, these poets succeed in constructing the communal space of living, of leaving, of presence and absence. Kim Hyesoon’s unique voice takes a special site of contemporary Korean poetics. Her language full of bodily experiences explores the inevitable impossibility of I and you, or the field where the possibility of the impossible is tried again and again. Her repeated calling forth of ‘the first’ makes every poetic tongue an origin of poetic utterance and experience. The barking, calling, trailing of mountains in ‘Seoul, Kora’ delineates itself a very public discourse coupled to an acute sense of history or historical consciousness.

Trades Hall, Melbourne

7 – 9 July 2011

l-r: Ann Vickery, Martin Harrison, Tom Lee, and Tim Wright.

How to sum up the Poetry and the Contemporary Symposium held at Melbourne’s Trades Hall under the auspices of Deakin University – three days of esteemed, associated, unknown, expert, dilettante, crystalline, recondite, modest, bold and blusterous papers and events – without recovering the territory mapped by the abstracts still available online, the insider anecdotes, the fast gestating and ribald rumours, or the deserving hagiographies required to celebrate the combined poetic curatorship of organisers Ann Vickery and Michael Farrell?

A list consisting of the titles of both papers and readings might begin a first account:

poetics and future scenarios: poems and poets in an age of energy descent and climate chaos. mez breeze and the cyber-syntax of code poetry. towards comics poetry. stochastic acts: the search string as poetry. fact or fiction: mediatations on mary finger. grand parade launch. vishvarupa launch. roundtable: poetics of unimprovement. calculated enjambment: continuity and discontinuity of rhythm in august kleinzahler’s poetics. sonic ekphrasis from william carlos williams to jackson maclow. a brief poetics. this is what it sounds like: performance poetry beyond postmodernism. writing country: indigenous poetics and the open field. “periphery”. an encounter with chen li’s ‘wooden fish ballad’ – as translated by chang fen-ling. voice, music, sound: poetic histories beyond the printed word. multi-tracking & ‘seeing on the retina’ in leslie scalapino’s pearl trilogy. alice notley’s contemporary mythopoetics. jacket and the worlding of australian poetry. alan brunton: charismatic absurdist. six types of experiment in new new zealand poetry. hidden in plain view: constructing the poems in starlight. durga, kali, sita, krishna and feminist identities in asian-australian poetics. there is no future, and the future is spanking. under the influence: leaving bloom behind. death and the poetics of teeming in yeow kai chai’s ‘memento mori’ poems. as the text bears witness: a reading of ‘es lebe der kong,’ prynne’s elegy to paul celan. eating and speaking launch. contemporary poetics and sapphic mythologies. give me vidas and razos: the life of troubadour technologies in the poetry of ted berrigan. entrepot poetics: john forbes’ critique of the contemporary. naming the voids of multiculturalism in ‘biral biral’: a new reading of the poetry of lionel fogarty. form and field in contemporary australian poetry. merely circulating: modern poetry and the status of document. things to do with perth. poetry as writing a vector. “australian poetry” and some reasons why we don’t need it. gender city launch. one under bacchus and career launch. steamer and rabbit special.

A paucity of ideas contemporary Australian poetics is not, though you might be forgiven for suspicion towards the last formal entry on the programme since it does sound like number sixty one on a Little Bourke Street Saturday yumcha menu, not the literary magazines of Samuel Langer and Jessica Wilkinson. Nor does this particular programme seem to succumb to either obvious tones a contemporary poetics conference or symposium might deploy, of either celebration or suspicion.

No, instead, as might be obvious, the approaches are widely sourced: cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism, ecopoetics, troubadour poetics, literary history, modernism, information technology, Steinian poetics, Badiouian poetics, coterie, biography, process, Cambridge School, New York School, postmodernism, experimentalism, mythopoetics, kinetics, breath, electronic publishing, and indigenous poetics. These are the road signs of what was otherwise a curatorship of papers by devotees, luminaries, appreciators and poets.

l-r: Ann Vickery, Samuel Langer, Ella O’Keefe, Melinda Bufton, Elizabeth Allen, Michael Farrell, and David Herd.

A concerted effort was made to fill the interstices of the critical programme with poetry, a collective recital of the single-line poem ‘I PUT YOUR LETTER IN THE GARBAGE DID YOU GET IT’ by Michael Farrell and a reading of Astrid Lorange’s new chap Eating and Speaking being some of a number of intra-programme events.

Moreover, Melbourne’s poetry embassy, bookstore Collected Works, received a thrum of conference goers for readings by David Herd, Cordite’s own Matt Hall, Ruby Brunton, reading the work of her father Alan Brunton, Martin Edmond, Kate Lilley, reading from her new Vagabond book Round Vienna, and Michele Leggott. Naturally, one must get their passport stamped when entering Melbourne for poetical purposes, only apt then that a portion of Poetry & the Contemporary take place at Kris Hemensley’s establishment, regaled by interstate, Australasian, and international poets.

On site at the Trades Hall in Carlton, the atmosphere of the conference was not only collegial as all conferences intend, but rather communal. This was aided in part by the single room, single panel-style desk at the front with a generously packed room of listeners on the occasions I attended. For me, it was the first time meeting many poets and critics in attendance: Jill Jones, Siobhan Hodge, Chris Edwards, Martin Harrison, David Herd, Kate Fagan, Lindsay Tuggle, Michelle Cahill, Astrid Lorange, Joel Scott, among others.

The opportunity for those who knew each other already to separate into private circles hardly came about, it seems we all had the opportunity to share our research with at least a handful of strangers. Ann and Michael’s choices in speakers then were canny in another regard, in selecting some of the most devoted and passionate scholars and poets from around the country to spend a few days encountering the poetic passions and curiosities of others, not simply a national caucus where members proffer their latest projects.

John Tranter and Justin Clemens.

Often, in such an account of a significant literary symposium one wants the critical gist, the tone of a new preoccupation, or a snapshot of today’s poetic horizon. As usual, the best critical material was that which encountered the criticism of others, often unknowingly.

Sam Moginie’s account of John Forbes’ Australianness in poetics as a kind of international entrepot was another way of accounting for Kate Lilley’s celebration of Jacket magazine’s role as an Australian outfit being read for the most part by Americans. Kate Fagan’s account of Chris Edwards’ collage as cipher of material experience might be seen as an example of the Rosetta stone that is Alice Notley’s curse tablets in Linsday Tuggle’s paper on mythopoetics. The use of Lee Edelman’s critique of ‘reproductive futurism’ as a methodology in poetics in Astrid Lorange’s paper could be seen as one precept of the ‘unimproved poetics’ model offered by Bonny Cassidy, Jill Jones, and Claire Gaskin.

Now these are my own associations and undoubtedly readers who had been in attendance as well as the speakers and poets themselves might have difficulty with my personal ascriptions of connective tissue. It is this very contention that proves the worth of such conferences, that the papers remain the same for two people but the lines-through across the scope of the conference be fertile and interminable. It seems Vickery and Farrell plumbed their proposals in aid of this very potential.

The profusion of book and journal launches in the interstices and evenings at the Bella Union Bar upstairs at the Trades Hall upheld the pertinacity of this symposium’s subject, the contemporary, not only in the present, but the instant. Lisa Samuels’ Gender City was a polyvocal spree, Michelle Cahill’s Vishvarūpa was delicately erotic, Astrid Lorange’s hallway reading of Eating and Speaking was goat-filled and glorious, Duncan Hose’s One Under Bacchus (pictured) was a monstrous truffle hound, Liam Ferney’s Career was searching and reminiscent, Benjamin Frater on DVD from the new 6am in the universe was diabolical, and the glossolalia of new cult journal-churchesRabbit and Steamer struck hieratic palms to initiate foreheads.

The profusion of book and journal launches in the interstices and evenings at the Bella Union Bar upstairs at the Trades Hall upheld the pertinacity of this symposium’s subject, the contemporary, not only in the present, but the instant. Lisa Samuels’ Gender City was a polyvocal spree, Michelle Cahill’s Vishvarūpa was delicately erotic, Astrid Lorange’s hallway reading of Eating and Speaking was goat-filled and glorious, Duncan Hose’s One Under Bacchus (pictured) was a monstrous truffle hound, Liam Ferney’s Career was searching and reminiscent, Benjamin Frater on DVD from the new 6am in the universe was diabolical, and the glossolalia of new cult journal-churchesRabbit and Steamer struck hieratic palms to initiate foreheads.

These are but some of waves of poetry ebbing through a collective madness surely encouraged and not attenuated by the findings of the research fraternities, gangs, cults and itinerants in attendance for the symposium; a sect of Janus. Strays and politicians knocked on the Union bar door demanding to be included, were sat before a brightly lit stage where Pam Brown reminded us of the commandments for sustainable poetics from a cultural and economic point of view.

John Tranter continued the Australian Poetry Library conversation with an impromptu speech on stage and may I assure you, reader, as chair for Pam Brown’s paper, not an iota of this was premeditated! John Hawke and Alan Wearne launched the Grand Parade. Gig Ryan (pictured) launched esquires Hose and Ferney and had us in absinthe cackles. Rabbit steamed.

John Tranter continued the Australian Poetry Library conversation with an impromptu speech on stage and may I assure you, reader, as chair for Pam Brown’s paper, not an iota of this was premeditated! John Hawke and Alan Wearne launched the Grand Parade. Gig Ryan (pictured) launched esquires Hose and Ferney and had us in absinthe cackles. Rabbit steamed.

Perhaps the organisers then knew that to stake a claim on the contemporary the symposium had to be in some manner participating in poetry’s present-tense. This we saw in spades in the secret readings, and then these auspicious launches, with introductions sometimes as dramatic and ecstatic as the books being launched. (Michael Farrell, Jill Jones, Alan Wearne, John Hawke, Gig Ryan: beware! When you launch with such verve every poet will pester you for introductions!) What a spotlight then, to be launching a book in this solar forum.

Sunday was an unofficial day of rhubarb and baked eggs for breakfast, Ern Malley debates, and book buying at Paul Croucher’s shop Red Wheelbarrow Books on Lygon Street in Brunswick, followed by an excursion to the Heide Museum. Born to Concrete, an exhibition of concrete poetry, was the reason for our excursion, its typographical ideas dazzling, with work by Ian Hamilton Finlay, Sweeney Reed, Alex Selenitsch, PiO, and others. Scotland and Melbourne. Early afternoon the skies opened, and the poets and critics dispersed.

Ann Vickery and Michael Farrell should see their Poetry and the Contemporary as a riotous success and responsible for reinvigorating an ebullience for contemporary poetics in its partisan schools, its independents, its exiles, and its present-tense. This symposium succeeded because it was constituted by criticism enamoured of poetry, poetry enamoured of life, and life enamoured of criticism and poetry. To take a line from the late Benjamin Frater’s 6am in the universe, where I take it ‘My forearm’ is the poem:

My forearm forces electricity down the blue throat

(‘The Argument’ 24)

and Astrid Lorange’s Eating and Speaking, where I take it ‘nipple’ is the poem:

nipple is delicious little catastrophes.

(‘Background’ 33)

Possession: poems about the voyage of Lt James Cook in the Endeavour 1768-1771 by Anna Kerdijk Nicholson

Possession: poems about the voyage of Lt James Cook in the Endeavour 1768-1771 by Anna Kerdijk Nicholson

Five Islands Press, 2010

From at least as far back as Heraclitus, scholars have been warning us about the irresistible and irretrievable nature of history. The past provides little that is stable, other than an unwavering reminder of the constancy of change. The task of entering history, therefore, is fraught with complications. Poetry might seem to rejoice in such complications, yet if it’s going to engage with foundational narratives about nations and cultures, it can fall prey to some of the regulations of more prosaic forms. Anna Kerdijk Nicholson’s Possession is an engagement with what is perhaps the foundational narrative of the Australian nation-state, the journey of James Cook to the east coast of Australia. And it is a major example of Australian poetry’s fixation with a past at once irresistible and irretrievable.

:etchings 9 – Love & Something edited by Sabina Hopfer et al

:etchings 9 – Love & Something edited by Sabina Hopfer et al

Ilura Press, 2011

Love & Something is the sub-header of :etchings 9, and the something seems to stand for the multitudinous meanings the word love can inspire – familial, romantic, love of nature, passion for work – and the variety of things that sit beside it such as desire, heartbreak, longing and memory. The vehicles for these themes range from poems both direct and symbolic, art created from and inspired by history, and fiction both realist and speculative. With the broadness of the theme and mishmash of styles, the issue lacks a certain cohesion, although this might be an attempt to avoid any homogenisation of the concept of love.

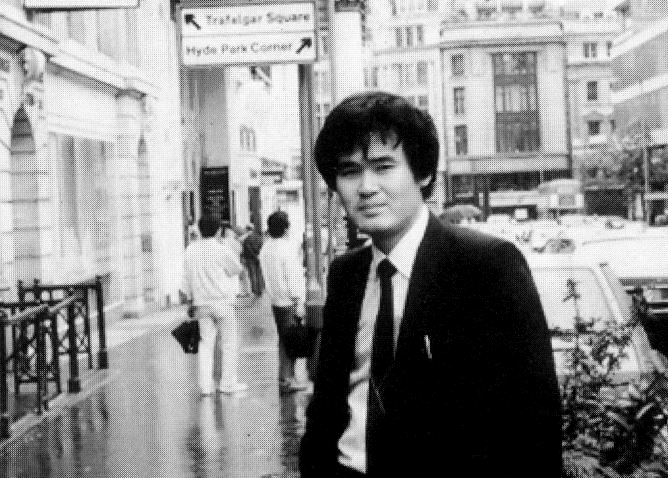

Photo from Beyond the Horizon

Gay/Poet/Korea – these were the first three words I typed into a search engine prior to undertaking the Cordite/Asialink residency in Seoul, South Korea. I’d typed these three words out of genuine interest in each – both singularly and collectively – but also out of a kind of frustration, having first consulted the section for gay travellers in the Lonely Planet guidebook:

In a country like South Korea, where social pressures to conform to a rigid standard of ‘normality’ are intense, it’s not surprising to learn that Koreans are intolerant of homosexual behavior. Lack of tolerance is hardly unique to Korea, but what is interesting is the lengths to which Koreans will go to deny, dismiss or rationalize the existence of gay and lesbian relationships. For most of mainstream Korea, homosexuality is a) non-existent or so rare that it’s hardly worth mentioning (so don’t); b) a freakish crime against nature; c) the manifestation of a debilitating mental illness; or d) a social problem caused by foreigners.

This section goes on to suggest that things are changing in South Korea, though it fails to state these changes as categorically as it does opposition to them. Perhaps this failure highlights the great disparity between a thing ‘changing’ and a thing having ‘changed’ but what of the subtle negotiations taking place daily for those that would benefit most from change?

And so, the search for more information.

Gay/Poet/Korea – it is not lost on me that with these three words I might well have been searching for myself, attempting to locate myself in a new context, a new country, but in the end the search produced Gi Hyeong-do.

‘Gi Hyeong-do: A Misunderstood Modern Gay Korean Poet’ was the heading. An article with a concise overview of his short but eventful life, from his impoverished beginnings, his father’s cerebral palsy, the death of his elder sister, his academic success and time as a journalist to his death at the age of twenty-nine in gay sex venue. A venue more often than not euphemistically referred to as a ‘movie theater’.

Three of Gi’s poems – ‘Grass’, ‘Front of the Bar’ and ‘Dead Cloud’ – accompanied the article. With the first four lines from ‘Grass’, my interest peaked:

I have an appendix but I don’t like eating grass I am a poor excuse for an animal

Whilst in Seoul, I sought out the translator of these poems, Gabriel Sylvian, in an effort to further understand the significance and impact of Gi’s work in South Korea, the subtle negotiations inherent in the translation process and the assertion of homosexuality as a fundamental and formative reality for Gi, a reality that shaped the narrative of his life and work.

Terry Jaensch: Gabriel how and when did you first come into contact with Gi Hyeong-do’s poetry?

Gabriel Sylvian: The first time I heard Gi’s name in connection with gay poetry was seven years ago, at a gay bar called ‘Contact’ near Hongik University Station. It was a karaoke bar (actually ‘dive’) in the basement of a run-down building a few blocks from where the Commission houses its grantees. I’d just arrived back in Seoul after ten years and was trying to get some sort of political project underway. After researching during the day, I’d go alone to the bar and hang out. Small groups of customers would come straggling into the bar after midnight for their second or third round of drinks and, just by chance, I got to know some poets and one or two teachers. One guy, a Korean literature teacher at a high school, mentioned Gi’s name in passing. ‘Gi’ is a rare family name in Korea, so at first I misheard it as ‘Gim’. It was a few days before I figured out his name, surprisingly written with the Chinese character for ‘strange’ (laughs). His work wasn’t hard to find since his Complete Works had come out five years before. I just borrowed the book from the library and started reading.

TJ: When did you first decide that you were going to translate his work?

GS: Once I got the book, I began with the shorter pieces, trying to get a quick sense of his style, themes, something. One of the shorter poems appearing near the beginning of the collection is titled ‘College Days’. It describes a college student, a loner intellectual, reading Plato on the school steps, or hiding in a grove of laurel trees at the rear of campus while shots sound in the distance. I checked the poet’s bio and saw he was a Yonsei student.

The shots, of course, refer to the clashes between student demonstrators and riot police that were a regular feature of campus life during the Jeon Du-hwan era. I’d lived just a five minute walk from that grove in the mid-1980s, in a Western-style house for international students near the university’s back gate. History professor Milan Hetjmanek, now at SNU, was teaching at the International Division that year, and Richard Krebill was our de facto house mentor. So I knew that grove, the old red-brick structures in the background of Gi’s graduation photos, and that same horrible sound. Yonsei University was a hotbed for student activism then. Classes were frequently cancelled due to tear gas explosions. None of we foreign students were psychologically prepared for it all. It all came back to me with that poem. The poem affects everyone who was a student in Seoul at that time in the same way, I think.

Gay cruising in Seoul was like a darkness within a darkness. You felt steeped in criminality at all times. Nobody really trusted anyone else. You had to keep your bag close to you or it would get stolen (laughs). Gi’s poems are dark and at first I just thought he was a depressed poet, maybe gay, maybe not. Later, when I found out through an article that Gi had died at the Pagoda Theatre, things came together more clearly to form a composite picture. So early on, by virtue a few coincidences in our backgrounds, it was easy to feel that I should try to translate his work. From that point I started thinking about how Gi’s life and art might be integrated into a political project.

TJ: There seems to be a great deal of conjecture surrounding the suggestion that Gi Hyeong-do was homosexual, even though he died in a gay cinema. What is your take on Korea’s inability, despite this fact alone, to even raise it as a question?

GS: The call for ‘proof’ is a central problem that the project has had to grapple with. The intellectuals in the gay community have always claimed Gi as one of their own, but I have sought proof. While translating his poems, I read everything Gi wrote, including essays and fiction, and every academic article, criticism and reminiscence written about him I could find. There’s not that much, really. Maybe less than one hundred articles. Except for one essay appearing in a book on postmodern Korean culture published in Europe, I found no mention of Gi’s sexuality anywhere in print.

TJ: That sounds extraordinary, but I’m guessing it was no shock to you?

GS: Well, who would ever expect to find a study of any Korean poet’s sexuality, gay or straight, or even poetry about sex? There were, of course, wild exceptions to the rule. Poet/novelist Ma Gwangsu, popularising Freud and free sex back in the 1980s, was arrested and tried by the Korean government on morals charges for, among other things, including scenes of homosexuality in his work. Then there was poet/novelist Jang Jeong-il in the late 1980s and 1990s. Similar charges were brought against him, too, by the courts in the 1990s. Tellingly, Gi did not shun, but showed an active interest in both writers. This is important background information to consider when thinking about Gi and same-sex sexuality in his literature. As for Gi the man? In the various recollections written about Gi by his colleagues, and in the testimonies of those whom I’ve interviewed (none of whom, by the way, seemed to know Gi very well – he seems to have been very private and is described as a loner), there are clues that stand out to the gay investigator and which support the theory of a same-sex orientation.

TJ: Can you elaborate on this a bit further, or highlight some of these ‘clues’ for us?

GS: Everyone I’ve met who knew Gi personally, for example, describes his speaking style as very effeminate. His taste in clothing was also consistent with an effeminate man’s tastes. He was known for his fastidiousness, meticulousness. Also, his family dynamic fit the classic stereotype of strong mother / weak father. Now in his prose, Gi once or twice mentions his own weakness, his ‘effeminacy’, in building relationships with women (though I think tellingly, never in his poetry, where the object of desire or address is ‘the friend’ or ‘you’) and this has been suggested by some as ‘proof’ that Gi loved women, negating the possibility of his being a homosexual.

First of all, anyone familiar with the Korean gay community – even today – knows that Korean gay men marry and have children. Some desire a conventional family, and sometimes this desire stems from social pressure. Marriage and family is what has been expected of all able-bodied men and in many cases, not doing so would mean being stigmatization as a social failure. From my interviews, I’ve found married gay men love their families but they feel this is not enough to satisfy them emotionally and sexually. How much more was this the case in the 1980s, when Gi was writing, than today? Before sexual politics.

The gay-straight dichotomy we so ‘naturally’ internalize as gay men today is blurred where identity politics has not taken root. This is especially true of men who were of Gi’s generation and older. So it is naïve, a mistake, to expect Gi to conform to present-day notions of a self-consciously queer poet with a solid sexual identity structure. Again, it bears repeating that gay Korean poets writing in the mainstream today, in 2011, are still not at liberty to publish same-sex poetry for their public readership. None of the poets I met at ‘Contact’ or elsewhere did. They didn’t dare try, nor any of their gay poet friends. So we certainly could not expect Gi to have done so. Directly, that is.

포도밭 묘지 1 (Vineyard Cemetery 1)

Gi Hyeongdo was born in 1960 in Gyeonggi Province, Korea. He began publishing poems during his college years at Yonsei University, where he majored in Political Diplomacy. He received the Yun Dongju Literary Prize as a university student. While working as a reporter for the Jungang Ilbo in 1984, he began publishing poems marked by powerful individuality and “an intensely pessimistic world view”. His formal debut was the New Year’s Poetry Contest sponsored by the Donga Ilbo for his celebrated poem FOG (Angae). On March 7, 1989, he died of apoplexy seizure at a late-night theatre in Jongro. Collections include BLACK LEAF IN MY MOUTH (1989, published posthumously), a collection of prose writings entitled RECORDS OF SHORT JOURNEYS (1990), and his COMPLETE WORKS (1999).

Read Terry Jaensch’s interview with Gi Hyeongdo’s translator, Gabriel Sylvian.

여름날 아침 낡은 창문 틈새로 빗방울이 들이 친다. 어두

운 방 한복판에서 金은 짐을 싸고 있다. 그의 트렁크가 가장 먼저 접수

한 것은 김의 넋이다. 창문 밖에는 엿보는 자 없다. 마침내 전날 김은

직장과 헤어졌다. 잠시 동안 김은 무표정하게 침대를 바라본다. 모든

것을 알고 있는 침대는 말이 없다. 비로서 나는 풀려나간다, 김은 자신

에게 속삭인다. 마침내 세상의 중심이 되었다.

나를 끌고 다녔던 몇 개의 길을 나는 영원히 추방한다. 내 생의 주도

권은 이제 마음에서 육체로 넘어갔으니 지금부터 나는 길고도 오랜 여

행을 떠날 것이다. 내가 지나치는 거리마다 낯선 기쁨과 전율은 가득

차리니 어떠한 권태도 더 이상 내 혀를 지배하면 안 된다.

모든 의심을 짐을 꾸리면서 김은 거둔다. 어둑어둑한 여름날 아침

창문 밖으로 보이는 젖은 길은 침대처럼 고요하다. 마침내 낭하가 텅

텅 울리면서 문이 열린다. 잠시 동안 김은 무표정하게 거리를 바라본

다. 김은 천천히 손잡이를 놓는다. 마침내 희망과 걸음이 동시에 떨어

진다. 그 순간, 쇠뭉치 같은 트렁크가 김을 쓰러뜨린다. 그곳에서 계집

아이 같은 가늘은 울음소리가 터진다. 주위에는 아무도 없다. 빗방울

은 은퇴한 노인의 백발위로 들이친다.

The raindrops beat their way into the cracks of the old window in the dusky summer morning. In the middle of the dark room, Gim is packing up. The first thing the trunk received was Gim’s soul. No one is peeping in at the window. The day before, Gim finally left his job. His face expressionless, Gim looks at the bed for a moment. The bed, which knows everything, is silent. At last I’ll be free, Gim whispers to himself, and finally he became the center of the world.

I’ll forever banish those roads that dragged me around with them. The leadership of my life has now passed from my heart to my body, and I will embark now on a long, distant journey. With each road I pass, I will be filled with strange happinesses and horrors, and henceforth, no lassitude must ever govern my tongue again.

Packing up all his suspicions, Gim gets everything together. The wet road visible outside the dusky summer morning window lies as quiet as the bed. Finally, the door opens, sounding a hollow cry in the corridor. For a moment, Gim looks at the road, his face expressionless. Gim slowly puts down the handle. In the end, his hopes and his steps both fall. That instant, the trunk knocks Gim down like a pig-iron. From the spot bursts a cry as thin as a girl. There is no one around. The raindrops thunder down on the gray head of an old hermit.

English translation by Gabriel Sylvian

주인은 떠나 없고 여름이 가기도 전에 황폐해버린 그 해 가을, 포도

밭 등성이로 저녁마다 한 사내의 그림자가 거대한 조명 속에서 잠깐씩

떠오르다 사라지는 풍경 속에서 내 弱視의 산책은 비롯되었네. 친구

여, 그 해 가을 내내 나는 적막과 함께 살았다. 그때 내가 데리고 있던

헛된 믿음들과 그 뒤에서 부르던 작은 충격들을 지금도 나는 기억하고

있네. 나는 그때 왜 그것을 몰랐을까. 희망도 아니었고 죽음도 아니었

어야 할 그 어둡고 가벼웠던 종교들을 나는 왜 그토록 무서워했을까.

목마른 내 발자국마다 검은 포도알들은 목적도 없이 떨어지고 그때마

다 고개를 들면 어느 틈엔가 낯선 풀잎의 자손들이 날아와 벌판 가득

흰 연기를 피워 올리는 것을 나는 한참이나 바라보곤 했네. 어둠은 언

제든지 살아 있는 것들의 그림자만 골라 디디며 포도밭 목책으로 걸어

왔고 나는 내 정신의 모두를 폐허로 만들면서 주인을 기다렸다. 그러

나 기다림이란 마치 용서와도 같아 언제나 육체를 지치게 하는 법. 하

는 수 없이 내 지친 밭을 타일러 몇 개의 움직임을 만들다 보면 버릇처

럼 이상한 무질서도 만나곤 했지만 친구여, 그때 이미 나에게는 흘릴

눈물이 남아있지 않았다. 그리하여 내 정든 포도밭에서 어느 하루 한

알 새파란 소스라침으로 떨어져 촛농처럼 누운 밤이면 어둠도, 숨죽인

희망도 내게는 너무나 거추장스러웠네. 기억한다. 그 해 가을 주인은

떠나 없고 그리움이 몇 개 그릇처럼 아무렇게나 사용될 때 나는 떨리

는 손으로 짧은 촛불들을 태우곤 했다. 그렇게 가을도 가고 몇 잎 남은

추억들마저 천천히 힘을 잃어갈 때 친구여, 나는 그때 수천의 마른 포

도 이파리가 떠내려가는 놀라운 空中을 만났다. 때가 되면 태양도 스

스로의 빛을 아껴두듯이 나 또한 내 지친 정신을 가을 속에서 동그랗

게 보호하기 시작했으니 나와 죽음은 서로를 지배하는 각자의 꿈이 되

었네. 그러나 나는 끝끝내 포도밭을 떠나지 못했다. 움직이는 것은 아

무것도 없었지만 나는 모든 것을 바꾸었다. 그리하여 어느 날 기척 없

이 새끼줄을 들치고 들어선 한 사내의 두려운 눈빛을 바라보면서 그가

나를 주인이라 부를 때마다 아, 나는 황망히 고개 돌려 캄캄한 눈을 감

았네. 여름이 가기도 전에 모든 이파리 땅으로 돌아간 포도밭, 참담했

던 그 해 가을, 그 빈 기쁨들을 지금 쓴다 친구여.

In autumn of that year, a year ruined even before the owner departed and summer ended, my poor-sighted walks to the back of the vineyard began amid landscapes where each evening, in the vast light, a man’s shadow flittered in and out of sight. My friend, I lived with silence the entire autumn that year. I still remember now the empty beliefs I carried with me and the small shocks that called out behind them. Why did I not know it then? Why did I fear those dark, trivial religions that were not hope and certainly not death? With each of my thirsty footprints black grape orbs dropped purposelessly, and each time I lifted my gaze I stared for a time at the progenies of strange grasses that came flying, stirring up the white smoke blanketing the fields. Darkness always singles out the shadows of living things so it can tread on them, and so it came walking to the vineyard’s wooden rail fence, where I turned my entire spirit to ruin and awaited the owner. But waiting is like forgiveness and always tires the flesh. I had no choice but to instruct my weary feet and make a few movements, and when I did I encountered various kinds of disorder, but my tears were no longer flowing. Then one day in my beloved vineyard, I fell from a bright blue orb of fright, and the evening lying like guttered wax, the darkness, the stifled hopes, all became too much for me. I remember. That autumn after the owner departed and when longing was used carelessly like so many dishes, I lit short candle flames with trembling hands. And so autumn passed, and when even memories with their few remaining leaves slowly lost their power, my friend, I came to a surprising space where thousands of grape leaves came showering down. When the time came, I too, like the sun conserving its light, began to roundly protect my weary spirit in the midst of autumn, and so death and I became our own dreams, each ruling the other. But I could never leave the vineyard. Nothing moved, but I changed everything. One day as I stared into the terrified eyes of a man who had stepped in from nowhere holding up the end of a straw rope, each time he called me the owner, ah, I turned my face away in agitation and closed my dark eyes. O friend, I write now of all the vineyards that return to leafy earth before summer passes, of the wretched autumn that year, of those empty happinesses.

English translation by Gabriel Sylvian

흩어진 그림자들, 모두

한 곳으로 모으는

그 어두운 정오의 숲 속으로

이따금 나는 한 개 짧은 그림자 되어

천천히 걸어 들어간다

쉽게 조용해지는 나의 빈 손바닥 위에 가을은

둥글고 단단한 공기를 쥐어줄 뿐

그리고 나는 잠깐 동안 그것을 만져볼 뿐이다

나무들은 언제나 마지막이라 생각하며

작은 이파리들은 떨구지만

나의 희망은 이미 그런 종류의 것이 아니었다

너무 어두워지면 모든 추억들은

갑자기 거칠어진다

내 뒤에 있는 캄캄하고 필연적인 힘들에 쫓기며

나는 내 침묵의 심지를 조금 낮춘다

공중의 나뭇잎 수효만큼 검은

옷을 입은 햇빛들 속에서 나는

곰곰이 내 어두움을 생각한다, 어디선가 길다란 연기들이 날아와

희미한 언덕을 만든다, 빠짐없이 되살아나는

내 젊은 날의 저녁들 때문이다

한때 절망이 내 삶의 전부였던 적이 있었다

그 절망의 내용조차 잊어버린 지금

나는 내 삶의 일부분도 알지 못한다

이미 대지의 맛에 익숙해진 나뭇잎들은

내 초라한 위기의 발목 근처로 어지럽게 떨어진다

오오, 그리운 생각들이란 얼마나 죽음의 편에 서 있는가

그러나 내 사랑하는 시월의 숲은

아무런 잘못도 없다

2

자고 일어나면 머리맡의 촛불은 이미 없어지고

하얗고 딱딱한 옷을 입은 빈 병만 우두커니 나를 쳐다본다

1

Sometimes I become a short shadow

and slowly walk into

a forest at dark noon

where scattered shadows

gather in one place

In my empty hand autumn, easily quieted,

just grabs the round hard air

and for a moment feels it

The trees always think it’s the last time

and drop their small leaves

but my hopes are no longer of that sort

When it grows too dark all memories

suddenly turn furious

Chased by dark inevitable powers behind me

I lower the wick of my silence a little

and in sunbeams garbed

black as the number of leaves in the air

I think in detail of my darkness, from somewhere straggling smoke wisps appear

and make a vague hillet, because of the evenings of my youth

which revive without exception

Once my life was just despair

Now even the despair’s contents are lost to me

I don’t know even one part of my life

The leaves already knowing the taste of the earth

fall dizzyingly near my shoddy ankles of danger

O, how memories of love always take the side of death

But the October forest that I love

has not erred

2

When I awaken from sleep the candlelight near my pillow has already vanished

Only an empty bottle wearing hard white clothes stares at me blankly

English translation by Gabriel Sylvian

속에서, 텅 빈 희망 속에서

어찌 스스로의 일생을 예언할 수 있겠는가

다른 사람들은 분주히

몇몇 안 되는 내용을 가지고 서로의 기능을

넘겨보며 書標를 꽂기도 한다

또 어떤 이는 너무 쉽게 살았다고

말한다, 좀 더 두꺼운 추억이 필요하다는

사실, 완전을 위해서라면 두께가

문제겠는가? 나는 여러 번 장소를 옮기며 살았지만

죽음은 생각도 못했다, 나의 경력은

출생뿐이었으므로, 왜냐하면

두려움이 나의 속성이며

미래가 나의 과거이므로

나는 존재하는 것, 그러므로

용기란 얼마나 무책임한 것인가, 보라

나를

한 번이라도 본 사람은 모두

나를 떠나갔다, 나의 영혼은

검은 페이지가 대부분이다, 그러니 누가 나를

펼쳐볼 것인가, 하지만 그 경우

그들은 거짓을 논할 자격이 없다

거짓과 참됨은 모두 하나의 목적을

꿈꾸어야 한다, 단

한 줄일 수도 있다

나는 기적을 믿지 않는다

It’s close to a miracle

that I’ve lived

I was moldy for what seemed an eternity

How can I predict my own life

in a damp dark world

in an order where no one bothers to look at me,

in empty hope?

Other people hurriedly take a few contents

and coveting one another’s functions

insert their bookmarks into me

Others say my life has been too easy

that I need thicker memories

Is thickness truly a problem when perfection is your goal?

I’ve moved several times, lived in different places,

but never paid a thought to death. My career

lies only in my birth. Why?

Because fear is a part of me

and because the future is my past

The fact that I exist, so

see there, what an irresponsible thing courage

Every person who ever looked at me once

left me, my soul

is mostly dark pages, who will ever open me?

But in that case they have no right to discourse on lies

Lies and truth must dream the same objective

and they can be found in the exact same line

I don’t believe in miracles

English translation by Gabriel Sylvian

(or, Someone’s Always Falling in Love with Korea and Doesn’t Want to Leave)

I am at the boarding gate of Incheon Airport, waiting for my flight to be called and for my return journey to begin. I am wearing large sunglasses, not because it’s particularly bright, but to mask escaping tears. The man sitting across from me happens to look up from the lurid covers of his Dennis Lehane book after I’ve been repeatedly dabbing at my face with a hankie. He seems a bit nonplussed.

Hovering above myself, the objective part of my brain is also bemused at my reaction. Really, what has happened in the two weeks in Korea to engender this ludicrous display?

When I arrived at the airport on 14 May 2011, I had no indication this was how it was going to play out. Uppermost in my mind was getting to my final destination, the Yeonhui Seoul Art Space/Writers’ Village. After meeting up with Asialink’s Nicolas Low, poet Dan Disney guided us towards a swift and spotless train into Seoul. We passed landscapes that evoked other places I’ve seen before: English countryside, industrial smokestacks, that section of track on the way from Sydney to Newcastle. Most of the time though, the view out the window was absolutely unfamiliar.

Jetlag wreaked havoc with my perception. Already I had almost lost my passport and the taxi’s seatbelt presented me with some difficulty. The pretty neon lights flickering past the car windows were turning quite psychedelic. Once we’d reached the Writer’s Village, we were greeted by Choi Jae-Sung who accompanied us for dinner at a nearby Korean barbecue place.

The ritual of Korean barbecue was a revelation. We sat cross-legged at a low table around a hubcap-sized hotplate as a cascade of side dishes came out from the kitchen, even before we’d given our order which, once it arrived, came to represent the embrace of conviviality I would feel throughout my stay in the coming weeks. Jae-Sung and Dan alternated turning over the meat, mushrooms, onions, kim chi and garlic as it cooked. Once it was ready, we helped ourselves. I learnt about pouring a drink for the eldest person at the table with both hands to show respect, and a couple of useful Korean phrases. Replete with food, when I finally turned in for the night, I felt distinctly more human.

Poet Terry Jaensch and Cordite’s David Prater arrived a couple of evenings later and we all trooped off to Hongdae to wander, ogle the urban nightlife and have more Korean barbecue, after which we toasted David’s speech welcoming us all to this new adventure with our soju-filled glasses. Due to staggered arrival dates, all five of the tour’s principal characters would finally come together three days after that first day at a rather impressive dinner, when the last of our company, poet Barry Hill, arrived just in time from the airport to sample some delightful dishes. The only things I remember were the tasty seafood, trying the seaweed soup and drinking some delicious makgeolli, a Korean rice wine.

The ensuing days would have been a blur had I not been taking pictures, documenting as much as possible. Even with the evidence, it’s hard to believe how much our programme managed to pack in and, due to the vagaries of the schedule, leave out. When time becomes a scarce commodity, some things have to fall away. The production and launch of a chapbook, a reading at Sogang University, and a more extended collaboration with the Yi Sang House project were among such casualties.

After the lull of arrival and settling-in came a whirl of names and name-cards. Armed with my two Korean phrases (annyoung ha seo for hello, kamsahamnida for thank you), I would shake hands, introduce myself and smile at up to five new people a day over the coming weeks. I don’t usually meet that many people in a month.

That most of the people I met had non-Western names just added to my near-constant state of confusion. Thank goodness they handed out their cards quite readily, otherwise I’d have been lost. This practice of exchanging cards would actually come to form the basis of our collaborative project with the independent (i.e. non-government-funded) publisher SAII.

Our official engagements had included a seminar in the Writers’ Village library, where we met our Korean poet counterparts (as detailed by David Prater in his piece). I was deeply impressed by the Korean poetry read to me during this event. There was the reading at Ewha Women’s University, where all three Australian poets shared their work and answered questions from the audience of students and faculty; the Seoul Literature conference, where Terry Jaensch delivered his paper; and the conference’s closing night party held at the Writers’ Village, where I shared the stage with acclaimed novelist Ben Okri, British ex-poet laureate Sir Andrew Motion and Nobel Prize-winner Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio.

This last event felt more than slightly surreal to me because I hadn’t known who else would be on the programme until about an hour beforehand. I’d heard of Sir Andrew, who was already poet laureate for five years when I arrived in Wales, and I remembered working bookstores in Hobart and Dublin and shelving Ben Okri’s The Famished Road — but I’d never met a Nobel Prize winner before that evening. My ignorance was a good thing because otherwise I would have been too awestruck.

People kept inviting us out for lunch and dinner almost every day, and we tried everything from barbecue and bibimbap to Korean fine dining. I remember, with particular fondness, the lunch hosted by the Korean Literature Translation Institute, when I sat between the poets Kim Ki-Taek and Hwang Tong-gyu, as I plied them with questions about gender equality, after one of the poets had commented how my poems did not have “feminist rage”. (I told him that he hadn’t read all my work.) I even fell in love with sujeonggwa, a cinnamon and ginger dessert tea, which I now know how to make after befriending my interpreter Kim Min Jung, who helped track down a recipe for me.

While I felt grateful for the attention and respect extended towards poetry and writing, I must admit I needed space to retreat and recoup my energy. Often it felt like there wasn’t enough time to process everything, especially things I found hard to take, such as touring the demilitarised zone. I treasured the times I had to exhale and let Seoul’s abundant aesthetic beauty soothe me. I found, for instance, that sitting by the conversation nook at the Writers’ Village, as the rain fell among the pine trees and the cuckoo bird sounded, very calming.

With so much going on, it was sometimes difficult to remember I was there in service of poetry.

I came to savour the hours when we weren’t on show and didn’t have to be on our best behaviour, those simple moments between engagements when we’d be travelling by taxi, subway or bus, in transit and just enjoying each other’s company. Mosquito-bitten, soju-drenched evenings, when we talked about poetry and love and relationships, or listening to bizarre, improvised songs voiced by a Star Wars character, which would send me off into giggle fits, incapacitating me from further conversation.

The official and unofficial spheres overlapped in a very pleasing fashion during our collaborative project with SAII. After showing us the shadow sides of Seoul over several days — which included a stroll past a red-light district and a visit to a shaman who foretold my future — and with deadlines looming, we had to decide how best to present our work. One quick brainstorm later and we had all agreed that, as a showcase for the poets’ response poems and the designers’ creativity, the name card was a portable and personal vehicle for expression. Perfect. How satisfying it was when we finally shared our cards on the final night. I found the audience’s response very gratifying, with many of our limited edition cards snapped up instantly.

It is hard to do justice to all that I had experienced in Seoul. Every day felt like a normal fortnight back in the real world. I wish that time could have elongated it further still — make it three weeks, a month.

It’s been over four weeks since I was at that airport, trying to compose myself, heartbroken over having to leave my friends, and the strange and wonderful time we had. Since I’ve been back, I’ve been trying to figure out how to return. Next time, I’ll be ready. I have started taking lessons. Jogeum hangug-eoleul ihaehabnida. I understand some Korean.

HEAT 24: That’s it, for now… edited by Ivor Indyk

HEAT 24: That’s it, for now… edited by Ivor Indyk

Giramondo Publishing, 2010

This issue of HEAT being named as the magazine’s last could indicate two separate things. One is the opportunity that arises from this; with each ending a new beginning could take place. The other is that the magazine might not be ending. In his editorial, Ivor Indyk cleverly opens with “Though there is always the possibility of a return, this will likely be the last issue of HEAT magazine in print form.” So we might endure a hiatus of feeling the sheer weight of each issue in our hands. Or we might have to convert to reading it online (an option with which Indyk seems quietly animated). Or we might have to say goodbye to the publication altogether. Whichever the outcome, this is somewhat monumental in the scope of Australia’s literary landscape, especially for poetry. Few high quality literary magazines have such a high percentage of poems per issue. I, and many out there like me, will miss that. But Indyk doesn’t play the over-romanticised gimmick card a reader like me might benefit from; this final issue has been produced just like any other issue of the magazine.

Graphic by David McCooey

Graphic by David McCooey

Whitmore Press, 2010

Porch Music by Cameron Lowe

Whitmore Press, 2010

Though relatively young, Geelong-based Whitmore Press’ poetry series already boasts strong collections by Barry Hill, Paul Kane and Maria Takolander, amongst others. With Graphic by David McCooey and Porch Music by Cameron Lowe, Whitmore’s winning streak continues. Both books brim with inventive, surprising and thought-provoking new poetry.