apparently by Joanne Burns

apparently by Joanne Burns

Giramondo Poets, 2019

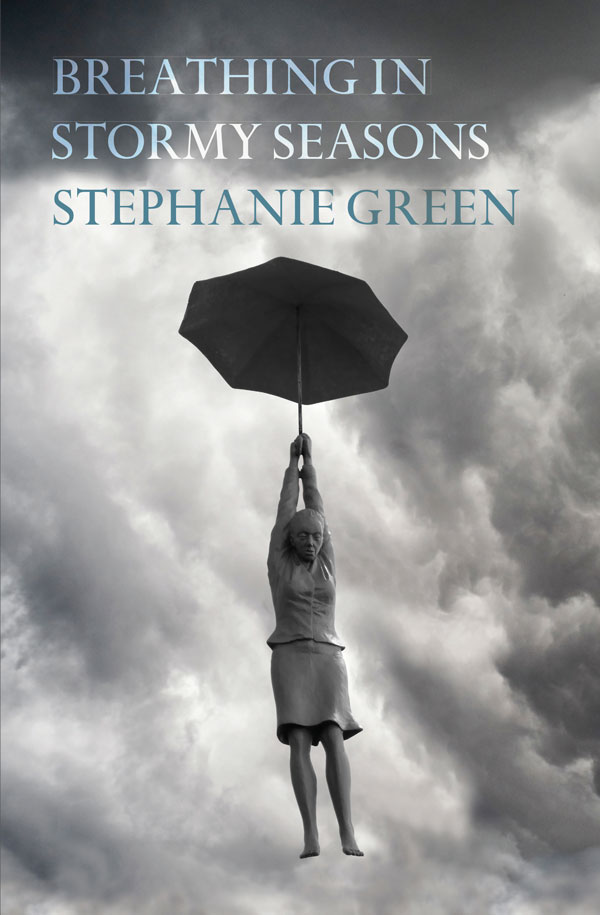

Breathing in Stormy Seasons by Stephanie Green

Recent Works Press, 2019

Parts of the Main by Jane Williams

Ginninderra Press, 2017

This is a review of three collections of poetry by women, two published in 2019, and one, Jane Williams’s Parts of the Main, in 2017. Of the two more recent volumes, Stephanie Green consistently uses prose in Breathing in Stormy Seasons, whereas Joanne Burns writes in prose in only one section of her collection, that which bestows its title, apparently, on the collection. Williams uses prose occasionally too, with her volume including three sections with prose works in each of them.

Burns refers to her prose texts as ‘prose poems or microfictions’ – I prefer the latter, because it allows us to circumvent the hazards of falling into a discussion about whether such works are poetry or not. Since many people seem to regard ‘prose poetry’ as an oxymoronic expression, it renders the expression rather ineffective. But the form isn’t so easy to differentiate from ‘other’, or ‘conventional’ poetry; which is generally the lyrical style of the poetry that dominated English writing during the nineteenth century, when many of the canonical collections still influencing our ideas today were assembled.

Prose poetry/microfiction uses many of the devices that lyrical poetry does; for example, it may use figures of speech or metaphor, or evoke sensory or emotional impressions with the sounds of words – assonance, alliteration rhyme or rhythm. The form’s key variation from more traditional styles of poetry is that it tends to foreground narrative or story over emotional or sensory impressions, or ‘feeling’ (which is otherwise well conveyed by the ‘non-wordy’ aspects of lyrical poetry – its sounds or rhythms). Where sensory perception is conveyed, visual perception is usually prioritised, which is what enables those writing in the prose form to dispense with lyrical poetry’s prosodic structures. Emotional and non-visual sensory impressions are thus demoted in favour of the storytelling or narrative aspects of the text. Perhaps it is the emphasis on visual perception, however, that makes this style of writing ‘poetry’ – its stories are told, or its narratives conveyed, at least in some significant part, through sensory perception rather than reasoned thought or ‘ideas’.

The foregrounding of narrative is very much in evidence in Burns’s microfictions. In the ‘apparently’ section of her collection she ‘recounts unsettling dreams’, and the texts certainly read that way. They have the visual quality of dreaming, moving from one scene or event to another in ways that may be unrelated, but which the mind strings together seamlessly – the reader’s imagination finds relationships, and in so doing, makes its own narrative. Here is an example, from ‘evaluation sheet’:

i dropped into the sanctuary of asclepius purely to sleep, investigate my future. i entered the long hall of the enkoimeterion and lay down waiting for morpheus to download. in the dream I was offered a plate of what looked like boars’ eyes smelling like leatherwood honey, and balls of cotton wool that cackled then buzzed like bees.

This extract has a strong visual component that encourages readers to construct a ‘world’ in which the other parts then take their places. This allows meanings to emerge as part of an enveloping narrative. But, apart from its visual aspects, the work invokes other senses – smell and sound, as well as the heavy pull of sleep. It offers insights into the strange workings of the human mind, as mini-battles play out between its different parts – the deep mind that wants to sleep, and the buzzing active surface parts that run their own programs.

Such works may be entertaining and offer psychological insights, however, I find that they don’t take me far beyond an initial ‘oh, that’s interesting’ reaction. Burns’s microfictions read as a dream journal, and I think that this is where the significance of her collection lies – as psychological case studies. The other sections include: ‘planchettes’, which ‘spring-board from the clues and solutions to crossword puzzles’, ‘dial’, that ‘acknowledges the bewildering sense of daily time and the dizzying spectacle of social and worldly matters’ and, finally, ‘the random couch’, which ‘presents a number of drifting poems, written while the poet was lounging on the sofa’. These sections trace the workings of the human mind in similar ways to the ‘apparently’ section. In so doing, they may offer a launching place for others to try following their own dreams and musings, and to learn about themselves and the way human minds work. This is of value; Burns’s work has been used effectively in schools to encourage students to write, to trace their own thoughts, and in doing so, to work on the important task of making sense of their own lives through the power of narrative.

Stephanie Green does not call her works microfiction, but writes that she ‘would like to call them “moments of poetry”’. This is insightful, for her description helps bridge the divide between poetry and the ‘poeticness’ of much prose. I have written already that I think poetry emerges when we attempt to express the less concrete, irrational or excessive parts of our experiences as humans, especially those that we sense and feel, rather than those we ‘think out’ in ways that we can express through more disciplined, grammatically logical or rational uses of conventional language (language of words, rather than of, say, visual expression, music or other aural utterances, or performance). Thus I think that we tend to call writing poetic when it has an ineffable quality, when it makes a direct appeal to our senses or emotions, but expresses that which we struggle to explain logically. This is particularly in evidence in lyrical poetry, but Green’s prose texts can be like this too. Her works often have a drifting, haiku-like quality.

Green writes that her approach is informed by an interest in the ‘confrontation between the shock of materiality and the sensitivity of imaginative apprehension’. She is forthright about this in the text called ‘Scar’, within which she probes the disjunct between what we can see or openly communicate between one another, and what we feel, and is significant, but is hidden and difficult to share:

There is an invisible claw against my face that never lets me go … Every day it reminds me skin is testimony … My skin may not record where your hand glides … But this thin cloak for blood and sinew shows how it is torn: a pane of falling glass, a surgeon’s knife. … Whatever else, I am knitted together by its claims.

Because they probe the indeterminate and contradictory, Green’s works can sometimes resemble Burns’s dream-fictions, reflecting the ‘boundless resistance’ of the world as we experience it; or how it doesn’t always make sense. In ‘The Catch’, she writes:

At first they seem nothing more than a small cloud of dust propelled out of dawn, passing over the cliffs and out beyond the purple cove. Closer now they are some kind of wave, animated angles rising and falling … I am breathless, surrounded amidst a fury of great wings trapping and sweeping the air … as the air falls away, as the ocean rises … I fall helpless towards the depths…

In such writing, Green questions the notion that narrative is a central feature of prose poetry. If her works contain stories, these often seem surreal or not quite cogent. If readers are looking for narrative, they will require introspection, as well as active questioning of the text, in order to force that narrative to the light.

Meaning can be elusive in Green’s work, but I found the glimpses of the world that she offers stimulating, and often deeply moving. For example, ‘Pre-Memory, Papua’ made me think about my own earliest memories, which I believe I now lack the ability to fully access due to having lost the Czech language I knew in my early childhood. Green masterfully depicts the excessiveness of such ‘pre-verbal’ experiences and the difficulties we may have in integrating those into our sense of self if we lack the languages necessary for this.

Under Glass by Gregory Kan

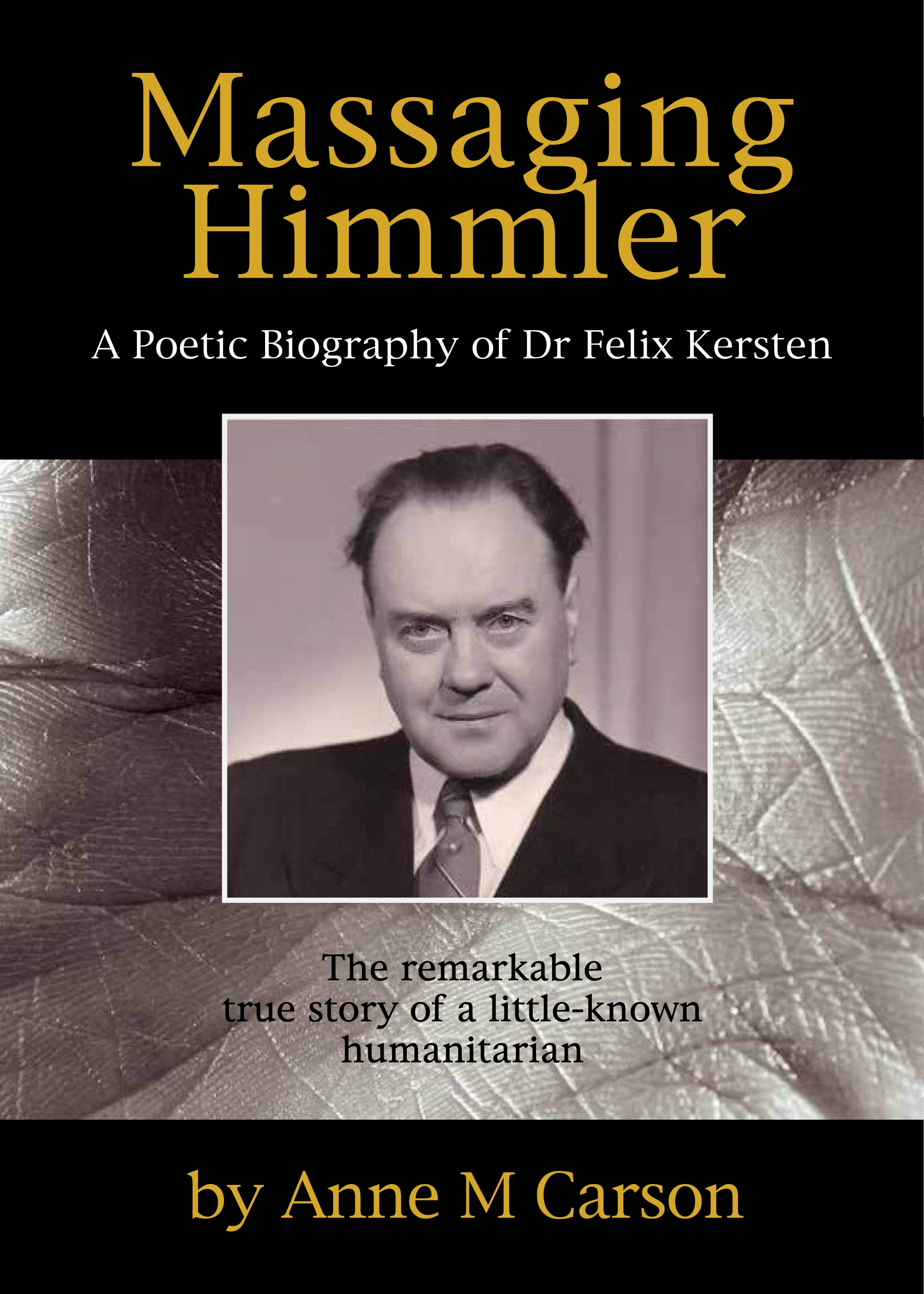

Under Glass by Gregory Kan Massaging Himmler: A Poetic Biography of Dr Felix Kersten by Anne M Carson

Massaging Himmler: A Poetic Biography of Dr Felix Kersten by Anne M Carson

apparently by Joanne Burns

apparently by Joanne Burns