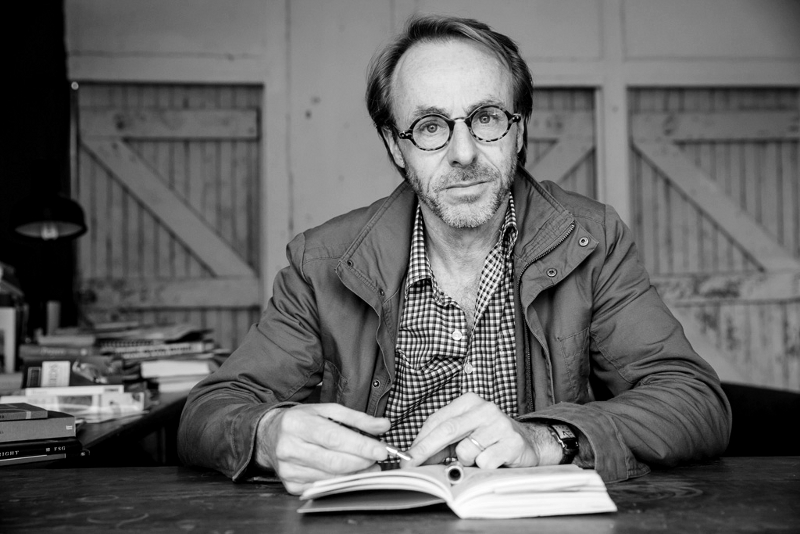

Photo from Pitt Street Poetry

I say ‘nature writing’, you see a Hallmark watercolour landscape replete with furry animals and woolly sentiment. But is this really the extent of it? What the hay is nature writing, or what isn’t? Where is the line between the natural and the human and, if there is any line at all, who put it there?

If anyone can clarify, it's Mark Tredinnick, vice-president of the Australian-New Zealand chapter of the Association for the Study of Literature & Environment, and accomplished nature writer. Mark's poems have won a number of awards, including this year the inaugural Blake Poetry Prize, and he has written expansively in his essays on the ecology of writing, where he describes nature writing enigmatically as 'nature, writing'. I asked Mark, then, what it might mean to write landscape, and to trace the meridian of the natural world in his own work as a poet.

Kay Rozynski: Firstly, what on Earth is nature writing?

Mark Tredinnick: Nature writing is usually prose, mostly nonfiction, mostly lyric, preoccupied with what we now, in Australia, might best call country. Barry Lopez – whose work embodies better than anyone's what nature writing can be at its best – says that in nature writing the landscape is the story. We humans are in it; but we are not the story; not this time. The story is the fabulous, discontinuous making and unmaking and remaking again of one place on earth or another; the story is the impossibly ornate interconnections that pattern that place and make it what it is, a work never finished; the story is also what all that makes of the people who attempt to make a living there. In nature writing, country is foreground; people are background. Nature writing runs on geologic, not merely human time.

Nature writing is a broad church. It comes grand and it comes humble. It will be pretty daggy nature writing that merely appreciates landscapes and glories in the wonders of their furry and floral citizens; it will be clich?©d nature writing that expresses, in that same old sentimental diction, the tireless and tiresome old longing for communion with Nature. In a good piece of nature writing, we human beings are understood and represented as pieces of a place, and humble, glorious, generally alienated elements of the natural history of a stretch of country.

KR: In your essay on Robert Gray you mention that, as a harbour dweller, Gray could write 'gritty, hip idylls – some of them urban.' What might an urban pastoral look like?

MT: Pastoral, as an aesthetic, is a place and a point of view. (And one way to understand nature writing, of course, is as pastoral.) Traditionally, pastoral – and once upon a time all pastorals were poems – concerned itself with paddocks and fields and streams, with sheep and shepherds – with rural working landscapes, in other words. But pastoral can transcend its customary geography. For pastoral is really a cast of mind – an opening out of the imagination and the senses into the natural world.

In my essay I wanted to suggest that some poets, including Gray, might be understood as pastoral poets even when there are no paddocks in their poems. I wanted to advertise the uses of the pastoral beyond its usual country, I guess to suggest a kind of post-pastoral. The pastoral has been aptly described (by Terry Gifford) as 'a discourse of retreat' from the city – almost from the real world – and I wanted to recast it as a discourse of return; to reframe it for a very urban century of ecological crisis as a point of view that might let poets and their readers see nature in its wild order and eternity, in its animal-vegetable-geologic otherness. Even when all one can see is the brick wall across the lane.

KR: Jonathan Bate in his book The Song of the Earth argued that colonialism and ecological damage, such as deforestation, have historically gone hand in hand. This was clearly the case in Australia. But what does this mean in literary terms – how has writing the landscape in Australia impacted on the landscape itself?

MT: It is beyond argument that the pastoral project on the ground, which has so damaged the landscape – think rising water tables, ruined watercourses, decimated woodlands, lost marsupial nations – was advanced and justified by the pastoral project in the mind. That is, the pastoral aesthetic (the rolling hills, the brooks and pastures and glades, the nymphs and shepherds, a very English idyll unspeakably at odds with the actual country in most parts of this continent), carried in the books and syntax and DNA and on the tongues of the settlers, blinded them to how the country actually went and encouraged them, in the face of overwhelming evidence that this was not England and didn't ever want to be, to try to remake Australia to resemble Wordsworth's Lake District or something similar and to bear the weight of the huge pastoral ambitions visited upon the landscape. Pastoral preconceptions biased the first few generations of white Australians against the way the land actually went. An Anglophone pastoral encouraged us to clear; it told us rain would follow the plough, and other sweet bucolic lies.

In literature, the power of the pastoral has kept too many writers from finding the diction and the palette and the timbres they needed to get Australian landscapes onto paper. Our sentences for way too long have sounded like they have their roots down in a lush green isle, where some of the hills really do roll, and where arid means two dry days in a row; where desert is a pudding misspelled. A truculently Anglophone pastoral sensibility and diction kept the real landscapes out of our heads and out of our books until well into the twentieth century, when Judith Wright began to catch the lyric. In his poem 'Black Landscape' Robert Gray has a stanza that seems to me to realise how you have to listen to the land here, not to the poets we love from another land (where our language was born):

A crow was blown away, with a shout; I thought of having to eat

such dry fibre. Keats didn't know

all about those syllables, 'forlorn', who'd never heard

a sound like the bushfire's crow.

So Australian literature – I mean the white kind, the ballads and the various strains of pastoral we wrote for too long in the mother tongue, in the Queen's English – has been complicit in the pastoral colonisation of probably way too much of Australia.

KR: Discussing eco-criticism as an emergent field of literary studies, Peter Barry categorises nature along a spectrum from the untouched (deep space and so on) to the profoundly cultivated (garden beds, lawns) and observes that it is the former that tends to provoke the literary epic or saga. On the other hand, the end of the spectrum that represents heightened human intervention is often the setting for lyric poetry. Your recent poem 'The Economics of Spring' (Meanjin Vol. 67, No. 3, 2008) inhabits for me an area between the two extremes; or rather, it's the sum of them: it's certainly a lyric but it seems to open itself onto the full panorama of nature. The poem's speaker, who is a poet, appears to invite nature to inhabit the act of writing. Can you say something about what being ecocentric might do to a writer's process and creative choices?

MT: I'm not sure I buy Barry's dichotomy, interesting though it is. What I do in both the 'untouched' terrain and the 'cultivated' – say, in a poem set here in the tame old Southern Highlands and in my prose book The Blue Plateau (UQP, forthcoming 2009), where I deal with bigger, wilder and more sublime country (the Blue Mountains of NSW) – is attempt witness. Something actually quite intimate. So I'd say it's about lyric apprehension: putting yourself about to listen to country and to participate in it, through your work, as a dancer participates in a dance. In nature writing, one way or another, you try to let nature write. Speaking for myself, I feel for wildness wherever and with whoever I am. I try, in other words, always to remember the world, which came first (as I say in that poem), and let it into my words.

I've written a whole book – The Land's Wild Music (Trinity Univ. Press: 2005) – that answers your question, as I recall it. In that book, a meditation on what I call 'the exteriority of the very indoor experience of writing authentic witnesses of place', I emphasise the rhythmic, bodily element of the writing process – the dance, not always pretty, with words, the movement of fingers on a keyboard – and how vital those elements, often overlooked by writers steeped in narrative, are for recalling the rhythmic, musical dimensions of landscapes. You can write a narrative if you like, or you can write a meditative lyric, but if you keep writing to the rhythm you felt in the place, you're likely to keep alive the lyric of the country, and in this way invite the country to participate in the writing.

KR: It strikes me as interesting, though, that we talk and write about going out to be 'with nature', as though nature were 'out there' and human being distinct from it, entering and leaving at will. Maybe opposing nature and human existence, if that's what the pastoral does, was never amenable to the Australian landscape. Do you think the pastoral can ever escape being an imported mode here?

MT: Oh, it's way too early to give up on the Australian pastoral. We haven't listened hard enough yet. If I didn't think it was possible to catch the lyrics of Australian places in English prose and prosody, I wouldn't keep writing. Specifically, I wouldn't have written The Blue Plateau, which, interestingly, is being subtitled (not my idea, but I quite like it) 'An Australian Pastoral' in the United States. But I have no doubt my confidence is misplaced, and I know I'll fail. The country will always elude the book, or the dance or the song. Most things will – one's self, one's great loves – but most of all the country around you that is so much older and longer and less verbal than you are. One can try, though, and one should.

But the pastoral doesn't oppose nature and human nature; it notices that in much of our social, economic and even spiritual thinking, we have fallen out of, and with, nature. Not that in reality a split is possible: we are organisms, whether we like it or not; we are natural first and last, and cultural only in the middle. The exquisite challenge we face in Australia is eroding English – the tongue in which our dominant culture plays – to let it sing the way the plateau sings, or the desert or the high country or the harbour or the beach or the narrow lanes of Enmore. (It would be different if we were writing in a language like any of the Indigenous languages, which evolved on this continent, with the continent itself and its peoples.) All we have is a language imported fairly recently to a landscape that spent a long, long time becoming itself without ever hearing a Chaucerian or a Shakespearean, a Keatsian or a Wordsworthian syllable.

The history of Japanese modern haiku was definitely male-centered until quite recently. There have been many superb female haijin; most of them remained in the “kessha (結社)” system (a “kessha” is a group or sect that is led by a master and usually has a hierarchical structure – followers adhere to basic rules their masters set up). The system and rules served positively for some, whose talents were rather nurtured than hindered by the fixed criteria. Others achieved their own voices outside the system, and their haiku reflect various interests outside or sometimes against male sensibilities.

The history of Japanese modern haiku was definitely male-centered until quite recently. There have been many superb female haijin; most of them remained in the “kessha (結社)” system (a “kessha” is a group or sect that is led by a master and usually has a hierarchical structure – followers adhere to basic rules their masters set up). The system and rules served positively for some, whose talents were rather nurtured than hindered by the fixed criteria. Others achieved their own voices outside the system, and their haiku reflect various interests outside or sometimes against male sensibilities.

Reality Dreams by Ouyang Yu

Reality Dreams by Ouyang Yu Anonymous Premonition by Yvette Holt

Anonymous Premonition by Yvette Holt The Sweeping Plain by Michael Sharkey

The Sweeping Plain by Michael Sharkey the edge of everything by Phyllis Perlstone

the edge of everything by Phyllis Perlstone

Networked Language: Culture & History in Australian Poetry by Philip Mead

Networked Language: Culture & History in Australian Poetry by Philip Mead

Splits, conflicts and difference within poetry are the zones in which the forward-thinking aspects of spoken word recordings continue to dwell. Sometimes, spoken word is an achievement that challenges our preconceptions of what poetry is, and what it can be.

Splits, conflicts and difference within poetry are the zones in which the forward-thinking aspects of spoken word recordings continue to dwell. Sometimes, spoken word is an achievement that challenges our preconceptions of what poetry is, and what it can be. When we began throwing around ideas for this issue, the notion of 'Pastoral' first came up as a joke. Because ever since god knows when, for reasons that always seem to depend on one's thoughts regarding the generation of '68, Australian pastoral poetry has often been affiliated with the hackneyed, with the excessively sentimental, and with the sweeping visions of European imperialism.

When we began throwing around ideas for this issue, the notion of 'Pastoral' first came up as a joke. Because ever since god knows when, for reasons that always seem to depend on one's thoughts regarding the generation of '68, Australian pastoral poetry has often been affiliated with the hackneyed, with the excessively sentimental, and with the sweeping visions of European imperialism.