In 2012 Flinders University decommissioned a set of powerful microscopes. Technologies long since surpassed, ETEC, JEOL, LEITZ and the VANOX ‘twins’ (scanning electron and fluorescence scopes) had been marked for scrap; their manuals, notes and schematics boxed for collection.

But before the whole armamentarium could be junked, a group of South Australian artists and writers staged a salvage run. Stripped and disassembled, the microscopes were requisitioned with their attendant documents and some specimens inside an abandoned pharmaceutical distillery in Adelaide’s inner west. ‘Analogue anarchy … an autopsy of the electromechanical era’1, described one participant, surveying the recovered wreckage. Art made in response to these blinded instruments was later collected in The Microscope Project, exhibited at the University Art Museum in September 2014. Included as a poetical treatment was Ian Gibbins’s How Things Work.

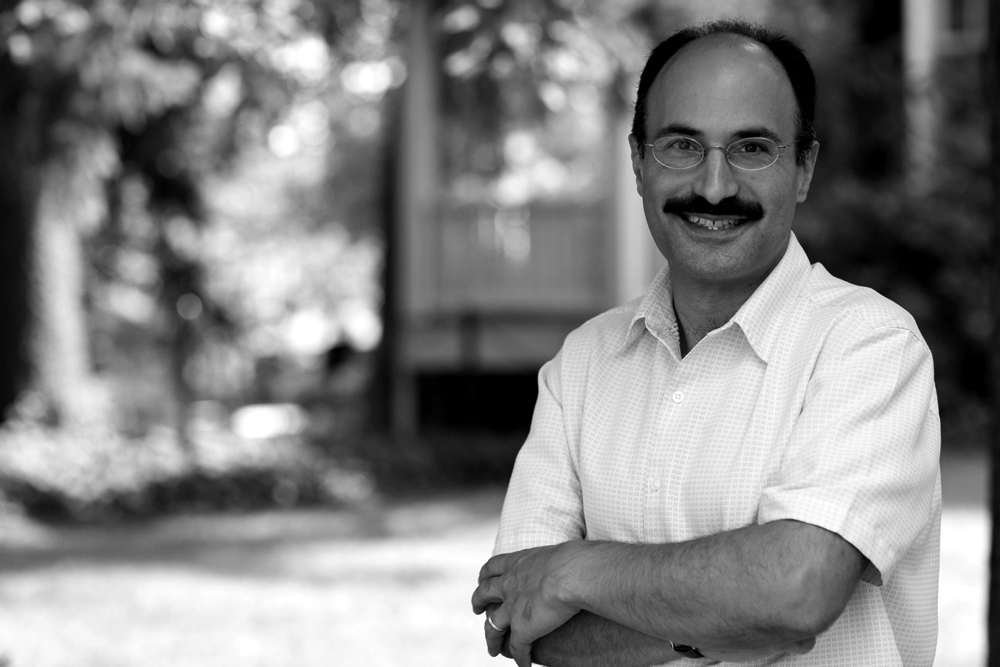

Until recently, Gibbins was a neuroscientist and an anatomist at Flinders. For him then, the microscope parts represented more than a mere puzzle or provocation – they were ‘deconstructed collaborators’, his gutted staff.2 Hence, these are poems interested in the sense-memory of machines, the mechanisation of language, and the possibility of accreted intimacies that persist between tool and technician. From ‘JK (Monday, morning)’:

This is how it works. First, you must plug it in, obviously, switch on the power, ramp up the voltage, check the vacuum status. You rehearse the operating procedures, the protocols required for your session. But you may as well be on the moon, holding your breath lest the oxygen supply drops to empty. You peer into the squid-ink sky, your feet aglow with dry volcanic dust, just trying to keep your hands out of trouble. Are you alone?

Object presence is one feeling explored in this collection: how does the human body register, and then swiftly forget, the optic implement standing between the looker and the looked-at? The uncanny effect of the microscope, Gibbins implies, is to remind the operator of their own, inbuilt perceptual apparatus – how the body sees with the twitchy rigging of optic nerves and the brain’s interpretative spackle in addition to its eyes. Do you, reader, perhaps also remember a time in science class, your brow pressed upon the unfocused eyepiece of the microscope, each eye seeing something wholly different from the other? Each eye in a world, unrelated? You shut one, maybe, turned Cyclopean to resist it because the experience was a little frightening – your brain out of phase with your vision. Such instants dislodge the textbook memory, I have two eyes and what they see takes some reconciling. In a click, it’s forgotten. Adjust the lens. Then, as Gibbins has it: ‘you may as well be on the moon … your feet aglow with dry volcanic dust.’ The microscope siphons the mind down onto the slide. The machine has become another link in a system of seeing.

Gibbins’s work explores how the operator can seem to have internalised microscope, even as the microscope closes in on human tissues. Forget the body, forget the lenses. Go into the cell. The minute rendered immense and mentally habitable. At the end of the lab the rubber sockets of the microscope are warm. Matching indentations encircle the technician’s face. The microscope reasserts its strange presence. Some microscopes emit a noise, a whine or hum, until they are switched off and de-animated.

Gibbins is a writer with a developed appreciation of the word articulate and its double meaning: to speak, and to extend by means of a further joint or armature, to add more structures to a chain of seeing that always was a collaborative affair (light, retina, nerves, occipital lobe, etcetera. A sequence to which we might also add various other machines today including telescopes, periscopes, satellites, cameras and smartphones). The poet wants the microscope to articulate in both senses, and so a number of the poems in How Things Work concede human creativity to machine language. See, ‘A Recommended Procedure for routine use as a “Working Standard”’:

maximum signal height minimize hysteresis minimum astigmatism onto the stage operational stability. or better. perpendicular to gold lines relocation of the images. suitable for this purpose 2 to 1

Circuit diagrams are reproduced, with line-by-line collages of troubleshooting guides for the VANOX, and a ‘Receiving Tube Manual’ for one electron microscope. Marjorie Perloff’s idea of unoriginal genius is cited as an influence here, alongside the constrained techniques of French Oulipo writers of the 1960s, and concepts of uncreative writing made popular recently by Kenneth Goldsmith.3 The strategy limits the poet to acts of associative logic and syntactic texture: repetition, reordering, pattern recognition. These commands are – in our current cultural moment, and in the context of this work in particular – identified as computational. They can be found in ‘Learning to Read and Write’ and ‘Vanox Observation Procedures’. But what is the effect of Gibbin’s thinking and speaking as a machine?

The thing to keep in mind here is that he isn’t. Gibbins’s language in these poems is not rendered in signals, zaps or data packs, light or magnetism. However granular, sterile or exploded the register becomes, the aesthetic still retains a humane charge. Gibbins’s ambition is not to de-centre assumptions of creative capacity (that poet must = person), and neither does the author offer a critique of social mechanisation. Rather, Gibbins is interested in material and intellectual collusions between poet/technician and microscope; in moments of co-recognition. This is why the poems in How Things Work can’t properly be considered mere acts of ekphrasis – however sculptural the defunct microscopes have become in their disuse, the inspiration moving between machine and poet is not unidirectional.

Thomas A Clark | Holderlin’s Shopping Bag |

Thomas A Clark | Holderlin’s Shopping Bag |

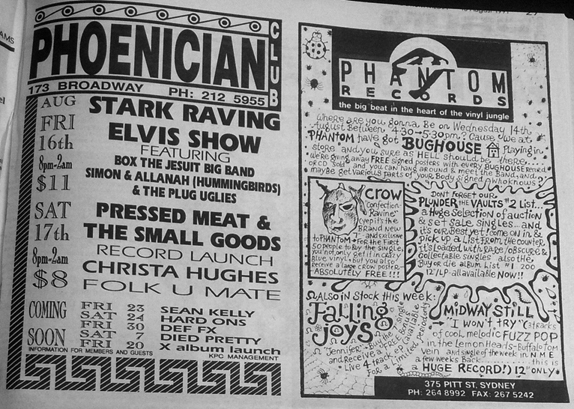

Advertisements for Phoenician Club (closed 1998) and Phantom Records store (also closed 1998), On The Street, Sydney, August 1991

Advertisements for Phoenician Club (closed 1998) and Phantom Records store (also closed 1998), On The Street, Sydney, August 1991