Fix breakfast, make coffee.

A sort of virtuous morning. No

hanging about. Wash clothes, dinner

—on the stove by 10.30, cooking,

ready for some time tonight

or another day. The plumber—who

could show any time—

(‘over from the mainland’) . . .

his day on the island.

Cath comes back

from swimming, headache gone.

& Lorraine arrives. They take off

for some market—no, an ‘open

garden’ inspection. We discuss

dinner together first—Ian’s plan

& ours. One or other we’ll

go with. I show

illustrations I have done

—a kids’ book for Finn & Max.

And they’re gone. No poems,

unless this is one. (This notebook

—one I’ve travelled with a few times—

hardly marked—phrases,

headings—fragments—designed …

‘to start a poem’, or make one possible

#

(notes from a day, a decade

or more ago—

beginning with a train trip:

things I’d have thought, or noticed

looking out the window, that

I did—or might have—

that drift off, to become notes

for a kind of poem (not

described) I’ve thought about,

but which would seem unlikely,

a chain of remembered moments—

of intensity, mindless focus,

happiness—none of them

in most senses, of any consequence

A number

instances of swimming, & of sensed

well-being derived from it—& a couple more,

similar,

added at a later stage, or signalled

just by their ‘name’

by which they will be recalled.

(A few are tagged

with a heading—’riding

bike’. Ha, ha.)

Nothing has come of them.

(A notebook

I look at, at two or three year intervals,

on trips, usually, to Sydney. Once at least to London.)

Then lines

that connect

to one specific trip … & a journey by train to Kurt’s

#

There’s a lizard appeared suddenly, on

the lower rung of a paling fence

six feet away, his body one

voluptuous curve as he

hangs there on an angle sunning

this must happen to everybody

& be, equally for all of them, like this

a ‘still moment’, the skink’s side

pulsing.

I remember one

I saw in Rome, & wrote in to The Circus—

an experience for The Strongman I think.

(Here it is again)

I’m reading

Ishmael Reed’s book Flight

to Canada. It’s very smart

& it’s very funny. Years ago

I read his The Terrible Twos, or the

Troublesome Threes or something,

which I also liked—tho maybe not this much.

#

If there’s a Greek term for it—

the poem about a putitative but non-existent poem—

Creative Writing could legitimately establish

a new time-waster (no—’genre’), one more

‘exercise’—as they have done,

to the detriment of poetry, with the Ekphrastic poem

a word I hate to see or hear

& wince in the expectation of—of the finished article, I mean—

the ekphrasm—

regularly drear, dumb—

short of what once was intended.

#

If there’s a name for it

“then it’s a thing,” as the present

would presently put it.

#

Kurt & I

go swimming—his place at Currarong.

He would hardly credit

how little I swim these days—how little

I have swum, over this last decade. In-

explicably. But I put on a show for him

& we swam & I enjoyed it.

Some of the other occasions—these moments—were at Coalcliff

or Stanwell Park, nearby—with Laurie, probably

& Pam, Micky, Sal & Erica

maybe Kurt. Another was at Burning Palm

—is that what it was called?—below a steep cliff

in the National Park. A tiny settlement

of tin houses, built first during the Depression

& allowed to linger—some remnant families—permanently

probably, unemployed. A few small children.

The same crowd—(of us)—in the water

The extraordinary thing—that I remember—

that the sand dropped away so quickly

We were buoyant, lifted up & down,

many feet, each wave—

(a tiny arc of sand—the beach—

just feet away), the tin dwellings pink

& blue & green & rust & russet

just back from it. The buoyancy—&

the friendship—made me euphoric

& I laughed. It was as if

they were the same thing.

Barbara was there too

& Kate probably.

One of my friends has fallen out

with his (former) best friend. How could this

be? It seems a dark note

to introduce. Too dark to be avoided

(Tho avoiding things, isn’t that what I’m

good at?)

The ethics of poems.

I wondered once—or, first, some years back

if it could make an autobiography

these best moments,

a sequence, a chain, a necklace of them?

to parallel my real biography

of family, relationships—&

reading, writing, work—my real life.

Two tales. A poem with a title like

Substitution, Passing, or Bowling Up.

What could be the name for this form or genre?

Nebulosa Prospectus? “Now

coming, soon, to be inflicted on the unprotected”—

Write a poem, about a poem, that you

haven’t written.

Mine would include other swimming moments—

one with Cath & the kids, Gabe & Anna. Yuri?

Tom? I don’t remember, tho I remember doing a drawing of it,

calling it The Life Aquatic after an old movie

from the 80s the 90s.

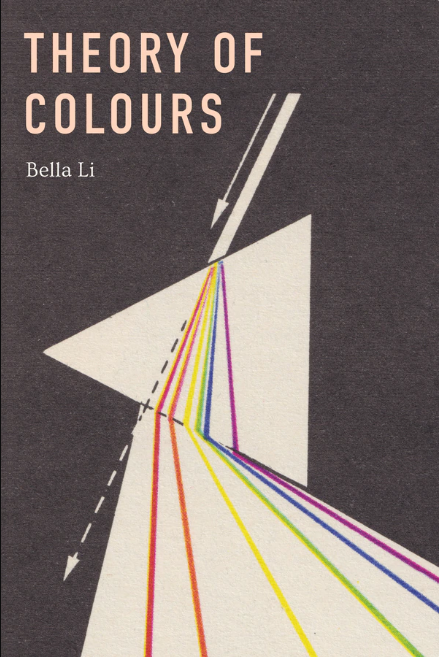

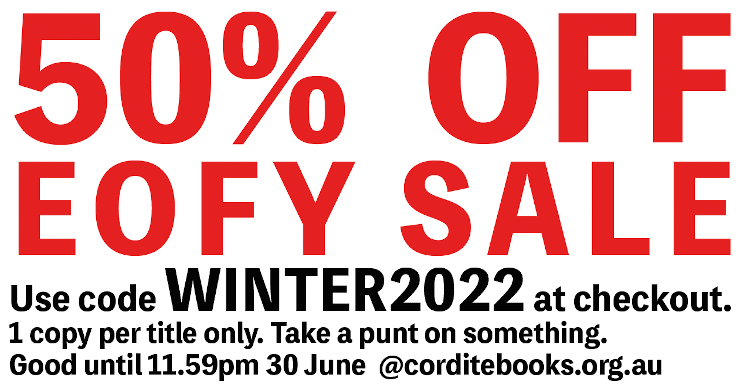

Theory of Colours by Bella Li

Theory of Colours by Bella Li

Bees Do Bother: An Antagonist’s Care Pack by Ann Vickery

Bees Do Bother: An Antagonist’s Care Pack by Ann Vickery