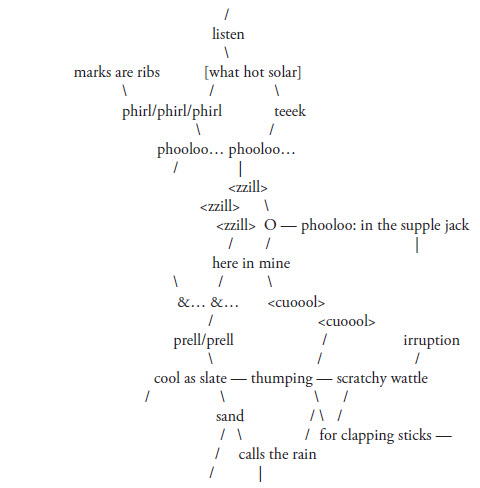

for John Jenkins

I Reach & Ambition

Late at night, up, looking at

the things on my mantelpiece

a profusion of crap, clutter & gewgaws

a range of detail I love (John’s photos of it

came today, reminding me). I look at the pictures

blu-tacked there, above—postcards of paintings

1900 to 1920s mostly

but some Manet, some Fragonard, a Boucher

Michael Fitzjames, a Chardin—a piece of paper,

yellowed, proclaiming “Honeymooners star

Meadows dies” (with a picture of Art

Carney, Gleason, & Meadows), a picture

of James Brown being ‘assisted’

to his feet

by a Famous Flame, a large photocopy picture

of Pam, 32 or 3 … Anyway, the Manet—

two white camellias glowing

against a black ground—makes me think

Look at things! & on that basis

I think I will search out

the book of Manet‘s flower-pieces

& then, depending what that does to my brain,

re-read the Tranter poem I find,

placed in the back of this book. ‘Loxodrome’.

And maybe I will

II Gone

Left of the mantelpiece,

beneath the Chardin (a small, be-suited,

silver-haired boy—regarding a spinning top

on the table before him), four

tiny spots,

of blu-tack ,

form a rectangle

where a stamp should be—a patch of torn envelope

& the postal stamp that was on it. Gone. John’s photos,

tho, reveal it to have featured a dalek.

U.K. recognition for Dr Who. I am relieved.

For months now I have been aware

of the missing stamp, & had looked about for it,

thinking it showed a Chance Vought

Corsair, a fighter aeroplane of WWII

that I had liked. (‘Liked’.) I had been a fan of the plane

in my teens—& surprised to receive its image

as an adult forty years later stuck on an envelope,

& looking so American, mid-century & ‘of its era’.

I don’t know who had sent it to me

tho there are only a few candidates.

But now I see it is only a dalek—was only a dalek—

& I care nothing for Dr Who. The fighter plane

will show up one day, within a book of poems,

marking a spot to return to—in O’Hara or

Towle or Berrigan, Padgett or Mathews—

& I will be surprised & admire it for a second

III (Further)

Further right—

beyond a photo, from the outside,

of the front of the house at Westbury Street,

where I lived nine years—a photo

Mary gave me, the house white, window-sill

& door pale blue, maybe the fancy iron lacework

at the eave below the guttering blue too

the whole framed by the green leaves of a tree,

the wood of the tree an angled dark accent

at the right … Anyway, near it

are some designs of mine, screenprinted

or water-coloured, & some pictures, with figures

(it occurs to me now)

grouped in threes.

One, rather Pop, shows a mother & father

clean-cut, at a restaurant, flanking their son—

the cartoon ‘Burt’ from The Muppets who looks

straight at us, while Mom & Dad look right,

alert to … a nightclub act? a waiter?—

something outside the picture. Of course

Burt looks bizarre. Above, women clean up the Reichstag

after WWII—three women, it appears—in fact

three pairs of women—bend, mopping or shovelling

at rubble, dark figures, shapeless,

dwarfed by the immensely tall

pale Greek columns of the ruined building.

Beside Burt & his parents, a photo from late 19th Century:

“The Match-girls’ strike: their pay was docked

to erect a statue of Mr Gladstone” says the caption.

High-waisted skirts & tight, formal blouses,

all with hats—their best clothes—one looks pretty

& all look aggrieved & sure of their cause—

then a Braque or Picasso abstract—smudged,

glowing grey, & brown, & white, of a kind called (once?)

hermetic

IV ‘Loxodrome’

John’s poem, John Tranter’s poem, ‘Loxodrome’, I was

about to call it ‘Lucasade’, is great.

On first reading I was conscious

mostly of its easily maintained urbanity

& its complexity, charting a move

from North to Southern hemisphere—

in a corkscrew motion?—via visits to certain

‘places’—New York, Paris, Australia—

& poetic spaces—Baudelaire, Ashbery-&-O’Hara,

Forbes—& to poetry readings & events, & then

his response. It includes two pieces of

information I recall giving John, knowing they

were his kind of thing—about Freud

& Arthur Hugh Clough. Now I read the poem

closely for the sense & grammar

of the construction. Good to have that clear.

In the poem John imagines me

spying on him thru the fence—as

he cleans the pool, pointing out

annoyingly, a leaf he has missed?

Then John Forbes, in JT’s dream,

notes an error in one of his poems.

In fact, I see a change that could be usefully made

myself, tho not necessary & I doubt

I’d point it out. “(R)ecalls, for us, a tireless

mechanical rocking horse / galloping evenly

over the heather, the rhythm / soothing

& slightly narcotic.” Would that be better?

Maybe not much. Maybe not at all.

V The things JJ liked

The things that John must’ve liked—

(tho he liked it all, the confusion)—

at one end of the mantelpiece a small yellow

monoplane, high-winged, its propeller & wheels

of a like yellow—an infant’s toy—one wheel

a little broken. It sits, like everything, wedged in,

between jars & dishes (of paper clips, pencils), pencil sharpeners (one

—one of these—in the shape of a nose), small bottles I must have liked

—for their shape & colour—two ‘metal’ milkshake holders

cast actually in ceramic, one with a bunch of pigs-bristle

paint-brushes rising out of it, like flowers from a vase.

The second one (both are mauve) has a small flyer

for a piano recital on Cortula or Hvar.

Ivan Pernicki—tho Ivan Pernikety

I preferred at the time. (It got rained out,

cancelled. We were going to go—the posters were all

over the island: Chopin’s mazurkas, I’d like to think.)

In

what looks like a small urn—ceramic tho it pretends to be

woven brush—

(coppery orange)—is a perfectly round

white or flesh-coloured ping-pong ball, with

a face painted on it comically menacing & ghoulish

with a black top hat: its amused eyes rest

just above the urn’s rim. (It’s mounted on

a toothpick, I know, so you could stick it in things

(food? A cake?) & was given to us by Yuri’s

then German girlfriend, Kathleen, from Dresden.

We never met: we were overseas: but she liked us—

liked Yuri—& left some presents for the house.

There’s a clothes brush I never use. Some stickytapes,

small staplers, a book cover—grey, proof copy—

for Pam’s Fifty-Fifty. There it is again, nearby,

in ‘full’ colour, & a vase from my childhood—

& perhaps from Dad’s, or did he gain it

as a wedding present?—

a toffee-brown, with a scene painted on it—

people sitting in an 18th century farm kitchen:

tables, chairs, an open fire

a bonneted woman sitting in a niche

against the wall knitting: passing time, but busy.

Back at the other end, near the plane, some

rusched paper snakes—that I think Sally Forth

gave me: they’re broken now but still look serpentine—

in fact, even more so. They were attached to sticks,

& almost invisible thread allowed them to move,

snakily. There’s a Paul Sloan painting—an image

on a postcard, behind the snakes (just below

Burt et famille); there are two Singer sewing machine

‘light-oil’ containers, why? & a picture by Micky

(Micky Allan), framed, of

a curiously carefree footballer (a goalie, I always think)

failing to make a save. (There are goal posts, pennants,

an indication of a crowd, behind.) Late in the day—

or maybe it’s early in the game, but it is

how he intends to go on. Right near by,

on the door of the clothes cupboard is a colour photo

(from The Guardian) of a guy—on the wing—running

full tilt, the ball (Rugby) clutched high

against his chest, skinny, head thrown back

ecstatic that—by his lights—he’s going to make it,

just, in the very corner in a moment. It says,

“David Humphreys scores one of Ulster’s two tries”

He looks like he’s missing some teeth. You want him

to succeed. The crowd are yelling & laughing.

He could easily be bundled out, you would think,

but he’s going to make it. I love it: human frailty

simple pleasures. What else?—Beckmann

(Lido). Martha Reeves & the Vandellas (beautiful

in very funny pants) Richard Widmark—

in a sixties suit & hat, narrow tie, pressed flat

against a wall, expectant, gun out—two

Joe Louis postage stamps, Stendhal, pictures by

Kurt, & one by Sal, a photo of The Nips—formerly

The Nipple Erectors—posed in the street, the lead singer

in a zoot suit, slightly crouched, legs apart, the sole

girl in the band amused at the boys’ antics

stands very still, holds her guitar, smiles; a drawing I did,

of a hat, for August 6th.

I did it

here in this room, under the fluoro, at the desk.

There’s Rauschenberg’s

chair—

combined with the painting, & Seb & Mill

& Mill’s baby, Hec.