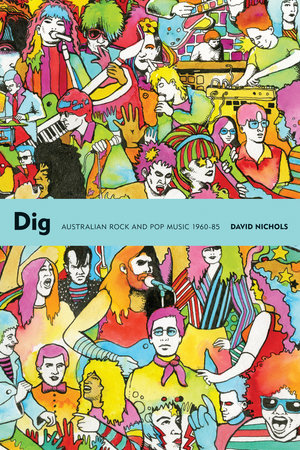

Dig: Australian Rock and Pop Music 1960-85 by David Nichols

Verse Chorus Press, 2016

Isn’t it time we invented a new handle for this ‘rock and pop’ stuff? ‘Rop’, for instance? Alternatively, ‘pock’ surely says ‘acne moonscape’: good for sounds designed to lure teens with condom-snapping haste. Regardless, I must say the droll and often delightfully irritated David Nichols brings a savoury palate to this tasting of Australian sounds. As a historian drawn to such antipodean delights as the subjects of his books, The Go-Betweens (2003) and The Bogan Delusion (2011), Nichols floats well above the bilge water line.

The foreword to Dig comes courtesy of Dave Graney, who notes that Nichols: ‘has experienced the limitations and constraints of the scene on the island and has continued to chase down rumours and will-o’-the-wisp reputations that occasionally spawn mad fevers in the compound.’ It is certainly true that, as this convict nation continues in its convulsive incarcerations, breakouts and last stands, songwriters and performers are the foot soldiers of escape. And with its bristling index and in-text scattering of old posters, cartoons and ads in black and white, Dig has a cannae-tie-kangaroo-down unpredictability. Nichols makes it clear in his introduction that he is not interested in cramming together all the old hack stories about rock stars acting up, or sniggering at historical ‘fashion crimes’. Rather he has rummaged through a range of evidence and conducted many interviews with musos and rock scribblers (including myself, disclaimer here) and others to plant his feet on the territory.

There are entire chapters dedicated to The Bee Gees, The Missing Links, The Easybeats, the strange story of the more obscure Pip Proud, AC/DC, Dragon, The Reels, The Triffids and The Moodists. Daddy Cool and Skyhooks are thrown into the washer together, where Bongo Star’s glitter irretrievably crunches up Ross Wilson’s foxtail. Other chapters explore the changing socio-musical decades. Along the way such interferons as architect Robin Boyd with his ‘Austerica’ (Australia / America) theory, the pianist, composer and free music explorer Percy Grainger and Richard Neville’s Oz Magazine-fueled rambunctiousness shoot through the text. Nichols dips into 1971 Daily Planet magazine to credit columnist Lobby Loyd with this ‘lobbying’: ‘Australian rock is probably the most advanced in the music world because this country has never known success, that perverter of truth and destroyer of progress.’ The crash-and-bash talent, unnerving persistence and musical nous are wonderful to breathe in.

The early-seeding festival scene is explored as a powerful multiplier of rock power. Nichols claims that South Australia’s three-day Myponga Festival in January 1971 only drew ‘an estimated 5,500’; recently, however, Bob Byrne wrote in the Adelaide Advertiser that he attended, and that Myponga, which starred Black Sabbath with many top Australian bands, had at least 15,000 paying customers and another 5,000-plus jumping the fence. Dig reports ‘heavy rain and icy winds no doubt made the experience unpleasant even before the Draft Resister’s Union tried to break down the fence, distributed pamphlets condemning the festival as a money-making concern, and at one point marched onto the stage chanting ‘out, pigs’ and ‘free concert’.’ The highly varied reportage on Myponga is challenging, and Nichols’s account funny, however I feel that his overall picture of Myponga is inaccurate. In the Australian rock festival scene, Myponga has always been quite celebrated as: one of the most impressive early Australian festival line-ups, with much of the weather hot, if dusty; and the birthplace of Daddy Cool’s enormous live success.

More commonly, Nichols has a solid grip on the ever-transforming and widening scene. Chapter Six, ‘Falling off the Edge of the World: The Easybeats,’ makes fascinating reading about the guys who in many ways wrote the bible on ‘How to Succeed in Show Business While Really Trying’, tripping over great cement clumps of failure en route, include Harry Vanda, Stevie Wright and George Young. ‘By 1969,’ writes Nichols, ‘Vanda and Young – at this point jointly the Brian Wilson of the group – were holed up in a flat on Moscow Road that had previously been a jingle studio for pirate radio … Somehow, the last proper Easybeats album, Friends, was made up almost completely of Vanda and Young demos, sung mainly by Young, including ‘St Louis’.’ Nichols quotes Vanda’s admission that, ‘I wouldn’t know what bloody St Louis was like,’ revealing that Friends was just an album to appease the contract while providing a taster of Flash and the Pan hits to come.

Another definitive moment in this sprawling history is when the talented Brian Peacock, known for the arty, rather baroque Procession – whose biggest hit ‘Anthem’, was completely a cappella – underwent a dark night of the soul. By this stage in the very early 70s, Peacock was staying at the Warwick Hotel in New York and road managing the American tour of the much more commercial New Seekers, when he discovered that their record company Warner Bros was owned by the Kinney Corporation, ‘basically car park operators … a heavily mobbed-up, mafia-riddled company.’ His resultant spiritual seizure ‘wasn’t drug-induced,’ says Peacock, ‘just a total paranoia that I was doing exactly the wrong thing, and the whole music industry was doomed and riddled with corruption.’ He told his business partners not to worry, he’d found someone else to take over, and as Peacock sensibly walked out, someone much more equipped to deal with King Kong – Glenn Wheatley – walked in.

There are also spiritual experiences in Dig of a purely musical nature. For instance, MacKenzie Theory (1971-4) were a highly skilled, electric ‘head’ band on the Mushroom label, improvising wordlessly on guitar, viola, bass and drums. Their American-born founding bass player Mike Leadabrand describes one show they played as ‘probably the most memorable event’ of his life. ‘It was as though the music came to us from somewhere else, and we were along for the ride as much as the audience,’ said Leadabrand. ‘When it was over, everyone knew that something had happened that we had no way to talk about.’ The Theory were supporting a popular Brisbane band that night, but that band announced they could no longer go on. Neither Leadabrand nor Nichols spells it out, but the implication is the headliners felt unable to follow the otherworldly experience their support act had conjured up. ‘Nobody complained or wondered why,’ said Leadabrand, about the headliners’ desertion. ‘This happened about three times in my three years with (MacKenzie Theory), and those times formed the person I would be to this day.’

Nichols isn’t always as sympathetic towards his subjects. After following the meanderings of Cold Chisel with attention in Dig, Nichols lets fly at their solo-going singer Jimmy Barnes for ‘the teeth-gnashingly ghastly’ single ‘Working Class Man,’ which, Nichols writes, is ‘written and produced by Journey’s Jonathan Cain, channeling a foetid, parallel universe Bruce Springsteen.’ Whether or not you agree with him, Nichols’s viewpoints are always individual, dodging the paralysing sameness often at work in long form rock-writing styles.

Wonderful, generous review of a book that never fails to illuminate, surprise and delight upon repeated re-consultation.