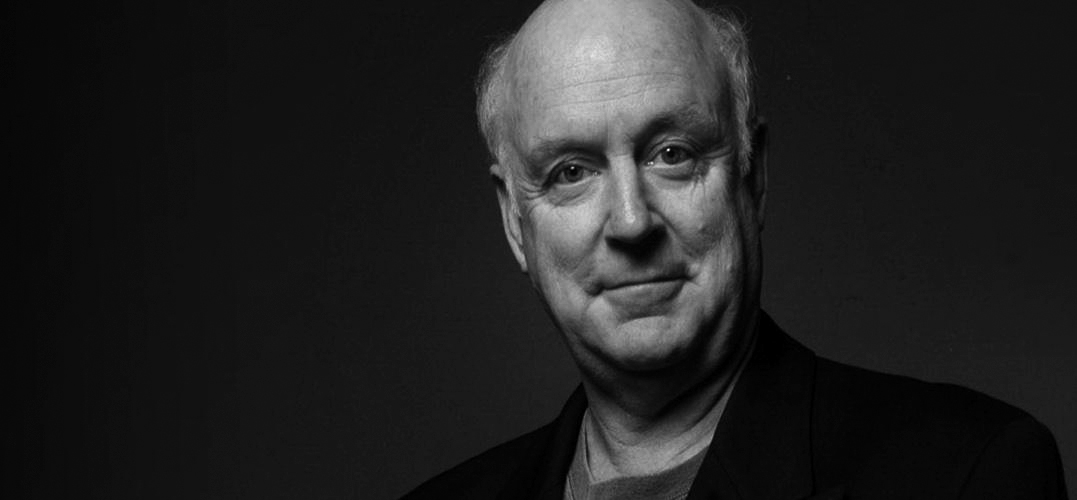

Image courtesy of Legacy

For many years it was assumed that poetry came from England. Research now clearly demonstrates, however, that a great many of the world’s most famous poets were actually Australians.

So opens John Clarke’s The Complete Book of Australian Verse – later expanded to The Even More Complete Book of Australian Verse – one of the most extraordinary poetry collections in the history of this – as Clarke’s Dylan Thompson would have it, ‘wide brown bee-humming trout-fit sheep-rich two-horse country’.

Clarke introduces a number of Australian poets hitherto unknown, whose work has a huge influence on English poetry. There is Arnold Wordsworth, ‘a plumber in Sydney during the first half of the 19th century … responsible for a good deal of the underground piping in Annandale and Balmain. He lived with his sister Gail and with his mate Ewen Coleridge, who shared his interest in plumbing, and also in poetry and, to a degree, in Gail’. And Emmy-Lou Dickinson, who ‘film devotees will perhaps remember Emmy-Lou as an extra in Witness which was directed of course by her fellow Australian Peter Weir … she lives alone near Lakes Entrance and speaks only to small children on her mother’s side’). And, a personal favourite, W H Auding, who ‘died in 1968, 1971, and again in 1973’. The book is the apotheosis of Clarke’s genius.

As anyone who has waded, stony-faced, through The Faber Book of Parodies will attest, literary parodies are not easy and tend, for the most part, to diminish both the writer parodied and the one doing the parodying. But here Clarke manages, astonishingly, to do the opposite. He reveals himself to be both a writer of extraordinary precision and suppleness (we perhaps knew that already) and listener of great acuity (the former no doubt due to the latter), but is able to reveal truths about the poets – their lives, their times, their form, even – and here is a real skill – their tragedies, their pathos.

Take Sylvia Blath, who ‘wrote quite a lot about illness and death. She sometimes did it ironically but always, behind all the fun, were illness and death. She called it a day in 1963’. Unlike her near namesake, Blath, in ‘Self Defence’ allows herself to reach the limits of language, revealing more about Sylvia Plath than any number of dissertations.

Your daughter you condemned to the oven Subtle in leather Der offen, schnell. Pig, brute, fatso, bastard Shit, bugger, bum, fuck, poos.

While his Tabby Serious Eliot (‘Old is what I increasingly seem to be’) finishes his poem with as piquant a summary of his namesake as can be imagined.

In the room the women come and go, Though not, perhaps regrettably, with me.

To do this, one needs more than a gift for parody. The book contains endless examples of Clarke’s brilliant ear form sound and form – from Labour Party leaders who ‘On remote coastlines … beach themselves / Spume drifting from their tragic holes’ in William Esther Williams’ ‘Carnival Music’; to those who would study ancient morals and observe that ‘at least one foot must be on the floor/While towing Hector around the walls of Troy’ in Section IX of Louis ‘The Lip’ MacNiece’s ‘What I Did in the Holidays’.

Clarke, by his own admission, came to poetry late, but became a devotee, writing lovely, revealing pieces – in his inimitable style, blending high and low culture – about a number of poets, including Auden (‘a natural history lesson includes the maxim that in polite company, you should never discuss politics, sex or religion. Auden was cleaning this theory one night when it went off. Almost everything he wrote about, and he wrote about almost everything, was politics, sex or religion’) and Seamus Heaney (‘when Seamus Heaney came to Melbourne in 1994, he had not yet won the Nobel Prize and could still play an away game’).

Poetry, Clarke felt was particularly propitious for parody, noting, in an interview with Justine Sloane-Lees for Radio National’s Poetica series that

… there aren’t very many forms, in writing, that you can adopt and collaborate with the original, but you can in poetry because of its brevity and its concision and because of the understanding that you have with the original because you’re collaborating with it when you first read it. So this is just another permutation of that collaboration, and it’s a pretty wonderful one to try.

This is every poet’s dream of an ideal reader – one who takes the care to ‘live with’ the poem, and to enter into a dialogue with it (the antithesis of the ‘what does it mean’ style of poetry reception taught in schools). For Clarke writing poems in the style of the originals was ‘like wearing someone else’s shoes and clothing, you walk as them, and all sorts of interesting things happen. You catch sight of yourself walking like someone else in the shop window’.

It is not hard to see the relationship between this and Clarke’s work with Bryan Dawe. I would argue that the key difference between satire and other similar forms of humour such as parody or caricature – or maybe just between good satire and bad satire – is that in the former the satirist, to some extent, empathises with the person satirised.

In this – the use of empathy as a way of engaging and satirising – Clarke reveals both his talent and his generosity, and this is, for me, why his political interviews were on a different level to other work in the genre. He didn’t simply mock the politician – an easy enough exercise – instead he asked the viewer to imagine being that politician.

To take as an example his final interview, where he played the Treasurer, Scott Morrison, Clarke doesn’t attack Morrison directly, rather, he imagines what it must be like to be Scott Morrison, having to defend a bad policy, and knowing that he will, almost immediately, be ‘hung out to dry’. Clarke’s ‘characters’ squirm, make desperate phone calls, engage in double-speak, attempt to make ‘Bryan Dawe’ ask easier questions, more intelligent questions, dumber questions, different questions. They are men and women forced to play dress up as politicians, and desperately wanting to be somewhere else – which is why Clarke himself didn’t need to imitate them. He makes the interviewee everyman or everywoman. John Clarke is them. We are them.