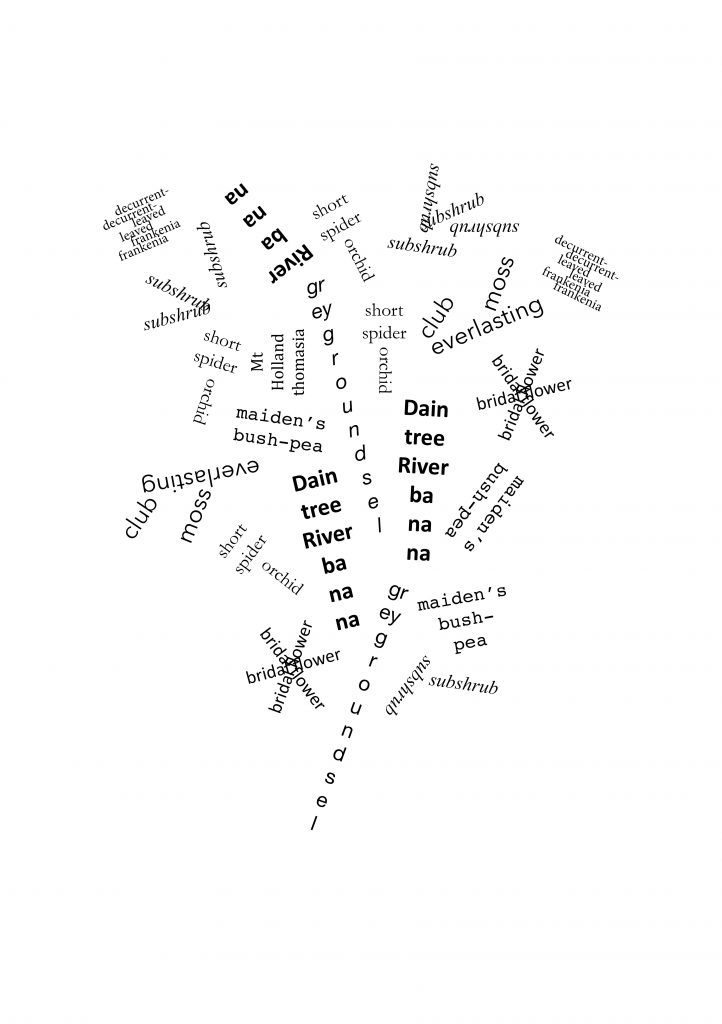

Image by Polixeni Papapetrou, 1999, State Library of Victoria

Gig Ryan is known for writing unusual, and challenging poetry. She published her first collection, The Division of Anger, in 1980. Ryan’s most recent collection, New and Selected Poems, was published in 2012. There is a lot to say. To begin, I think of lines that stand out through sheer intensity: ‘this slop hovering in the background like a new Hawaii’, from the poem ‘So What’ in Manners of an Astronaut (1984) is one of the scariest and funniest images / insults I have ever encountered. Reading Ryan as ‘a man’ is to be a sort of target, though not entirely as her work’s feminism, encapsulated by the renowned poem ‘If I Had A Gun’ (The Division of Anger, 1980). This sentiment is not the most salient feature of Ryan’s poetics. And not all of Ryan’s ‘intensity’ is in attack. There are memorable characters, both from myth – Eurydice, Penelope – and down the street, to the (for me) mythic figure in ‘Newtown Pastoral’ who ‘tells me about his pet turtle / and the pregnant daughter next door.’ Through condensed language, Ryan makes vivid portraits of believable but totally slippery figures whose lives we see acutely in one line only to vanish in the next.

Where do they vanish to?

‘Meet the subset, inventing dinner’s / folio of lanterns above her art of shrinking women’ ends ‘Albatross Diagram’. This exemplifies Ryan’s poetics as something like ‘pure poetry,’ a line of words shimmering pleasantly and freakishly between Kristeva’s symbolic and semantic realms. That, at least, was my apprentice’s take on her work, trying very hard to make sense of a poet I loved but didn’t ‘get’, leaning on theories also just beyond my grasp. I wanted (still want, and why not?) to read Ryan in the vein of Roland Barthes (described by Terry Eagleton): ‘the reader simply luxuriates in the tantalising glide of signs, in the provocative glimpses of meanings which surface only to submerge again.’ But this experience of deference to the work’s absolute potential reaches an endpoint at which we, or I, begin to ask questions searching for ‘meaning’. ‘What is the meaning of this “ungraspability”?’ might be one such question, but one I chose to avoid for fear of getting bogged down into specifics—especially when Ryan’s poetics work to resist such restrictive boundaries.

‘Ungraspable’ is perhaps an apt descriptor of Ryan’s poetry rather than ‘difficult’, which implies bad manners or ‘wilful obscurity,’ asserting that the work makes ‘perfect sense,’ actually, only hums on a plane marginally beyond. The work’s meaning is fairly clear to the poet, as you will witness unfolding in this interview.

Ryan is clearly one of the great Australian poets, especially if the job of poetry is to make us pay harder attention to the forces of language – as opposed to patting us on the head like a ‘good boy.’ To be ‘ungraspable’ implies constant movement toward something other. This will always be a more demanding way to live and be – but will never be boring or limited if sought out.

Gareth Morgan: Aside from appearing on the cover of your first book, The Division of Anger, there is not a lot of ‘you’ in your work. Through various means ‘you’ obfuscate yourself in poetry. One strategy is roaming pronouns. But even when there is just one ‘I’, and though we might be tempted to look for Gig Ryan the real person, a heavy surrealism dominates the view. Can you talk about why you don’t show yourself in poetry, which is a form that for many is ‘confessional’? What do you make of the general turn to the first person in a lot of new writing, including poetry?

Gig Ryan: I don’t read poems looking for the person, I am not interested in confessional poetry as such, though I used to be accused of writing it. The confessional poets flashing their stigmata are seen as Plath, Lowell, Berryman, Sexton, though each is more sophisticated than that label, which is usually meant to be disparaging, and poetry with the rest of the world has changed radically since their post-war 1950s era.

Confession in poetry is always a contrivance because it’s been arranged into an art form. ‘All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling’ as Oscar Wilde put it. The person writes the poem but is not presented in bullet points, as if that could even be possible. How poets arrange words together travelling from one idea to another tells you how they think more than their diary entries or medical records. The ‘selfie poem’ that uploads daily transactions and interactions, or that worships its trauma, is often more therapeutic than concerned with aesthetics. But there are also great poems that climb out of that framework, and confessional poetry has often drawn attention to injustices. Labels such as ‘confessional’ seem pretty pointless though we use those labels as shortcuts. I don’t care how poets write or what they write about, as long as it works and doesn’t send me to sleep.

GM: ‘Fallen Athlete’ is a poem that has jumped out at me rereading your poetry in the last year. It made me think of your work as somehow athletic. What do you make of this comparison? Do you think poets are like athletes or is it a different, maybe incomparable kind of work?

GR: ‘Fallen Athlete’ refers to the pursuit of something – the absorption that makes everything else fall into oblivion. That’s something everyone feels whether they’re a mechanic listening to a car engine or an opera singer or a writer or a runner. You fall into the rhythm of the task, the vocation.

GM: Despite having a clear theme, it is hard to predict what will happen next in your poems. This might have something to do with your tendency to write in the present tense. (As opposed to what might be called a poetics of witness, say, Kate Lilley’s Tilt, and many recent poetry collections which recount the past). Is this tendency a deliberate choice or does it happen ‘naturally’?

GR: Poetry is inventiveness, so it can’t be predictable. Maybe someone (sadly misguided) might set out to write a poem that is ‘clear as day,’ but it is impossible to think of any good poem from any era in any style that is predictable because as soon as you start writing you’re exploring what isn’t known. I will always wonder what Marvell’s ‘The Mower Against Gardens’ means in each line, and I laugh at the surprises in Byron’s ‘Don Juan’. I am intrigued by Milton and Marvell and Wyatt and Berrigan and Plath and Hejinian and Bernstein, as some random examples, or more locally joanne burns or Pam Brown, many others. In that sense poetry is always bristlingly present, invaded by remembrance of past poetries, and so it can never be static which is to be dead. What’s clear to some people won’t be clear to others of course, but too bad. I, as the poet, can’t heal the puzzled reader, only, with luck, entertain.

I want to be flabbergasted reading a poem, not patted on the head and reassured that I know what’s coming. If I could see what’s coming, I’d run a mile. In a way one wants to be accurate and clear but what to be clear about can’t possibly be known before it’s written; one poet’s clarity is not the same as another’s. Clarity can mean adherence to the flux of how one experiences life, so a poem won’t read like a walk/don’t walk sign but it’s an accurate depiction of tumult, of thought forming. Poetry is how poets think.

To dig out the rusty old O’Hara line from his ‘Personism: A Manifesto’, if you want to send a message then use the telephone – which is similar to saying that poetry is what can’t be said any other way … which many of course have said. That is, the meaning of a poem can’t be like a starting block that pre-exists outside the poem. Meaning can only be in the words as they’re being written, and the meaning will constantly fluctuate and construct itself as the poem is forming … and then get re-constructed, usually entirely concocted, by the reader or critic.

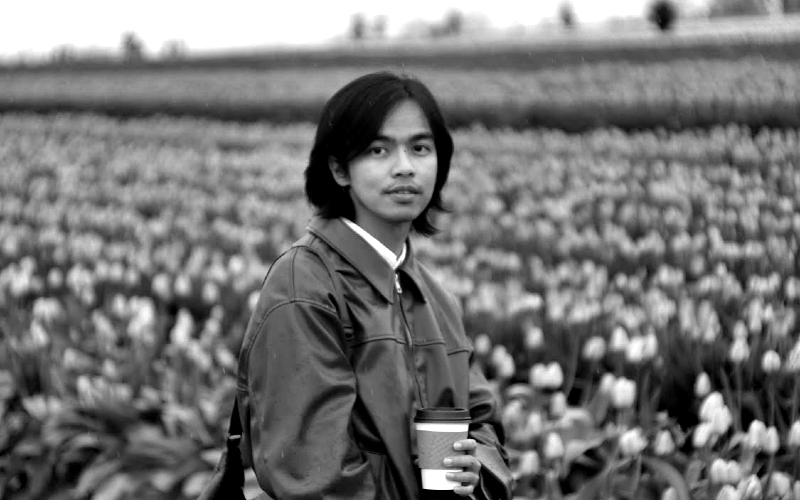

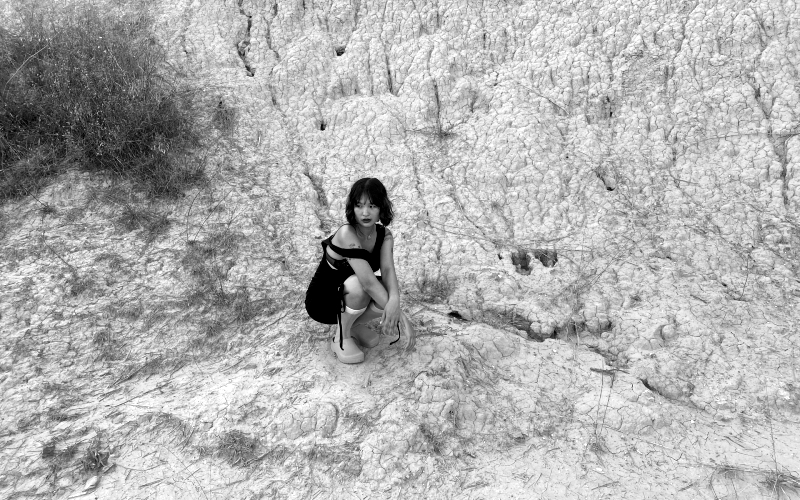

Photo by Cato Lein

Photo by Cato Lein