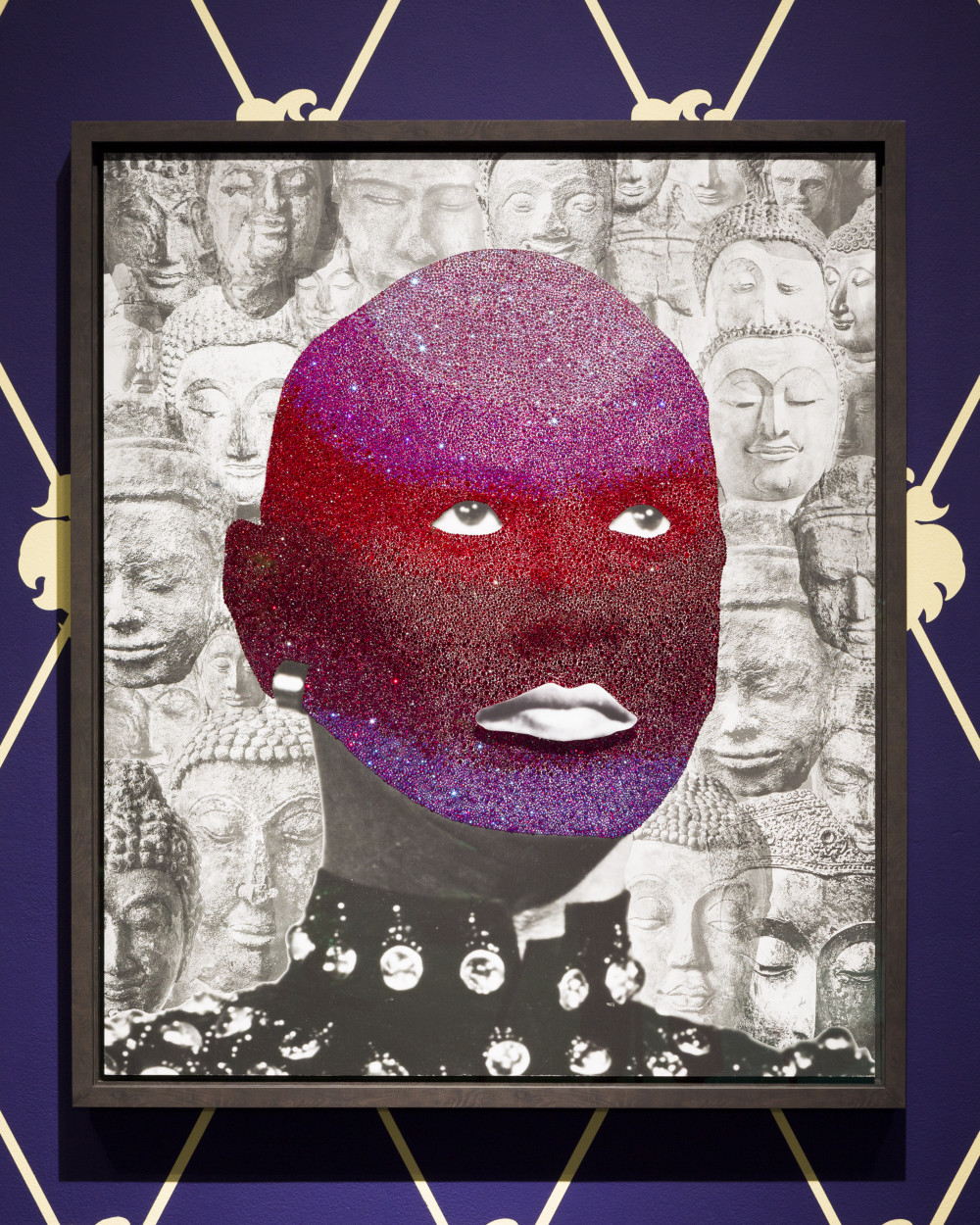

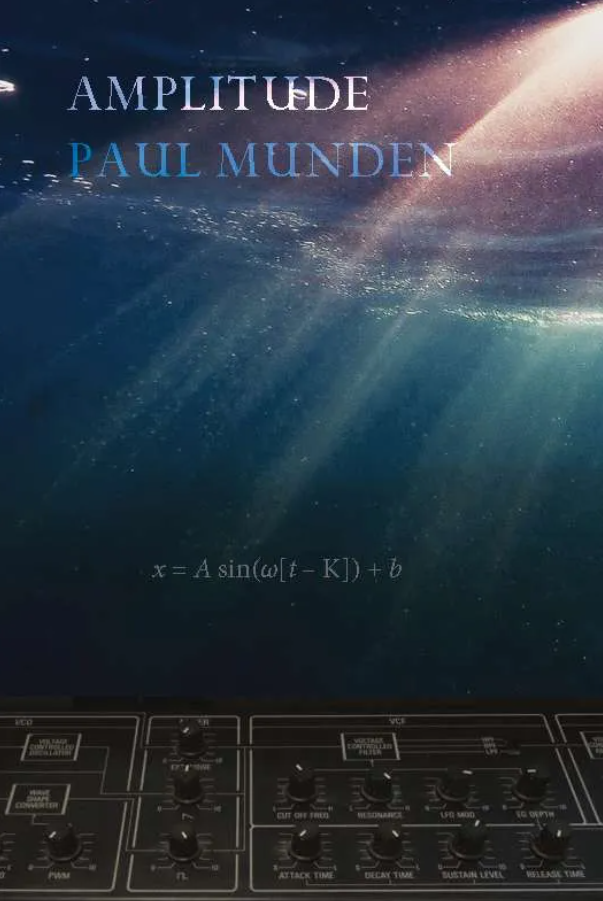

Amplitude by Paul Munden

Amplitude by Paul Munden

Recent Works Press 2022

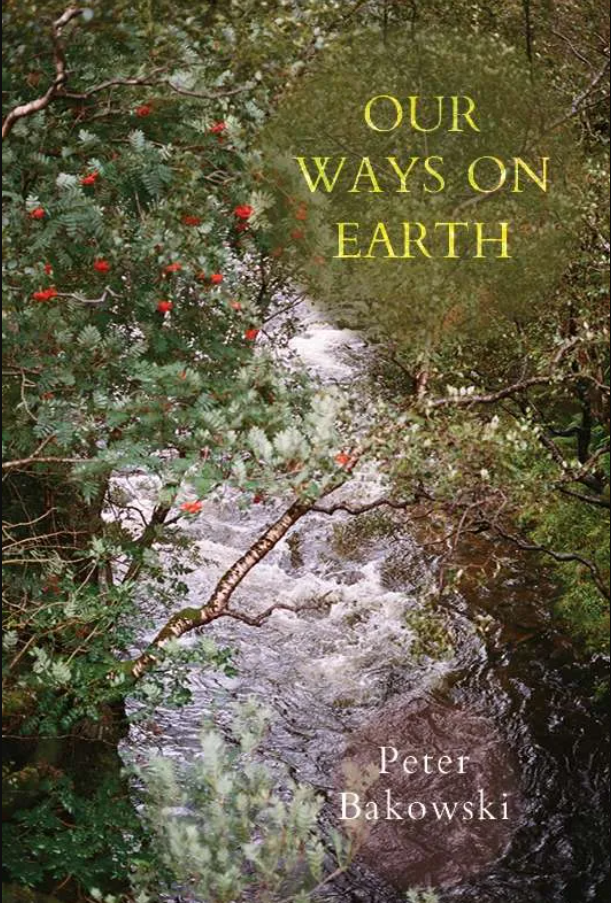

Our Ways on Earth by Peter Bakowski

Recent Works Press 2022

I do— I want that sensory

fill, that startling stereo-

phonic effect of time

- Paul Munden, ‘Greensleeves,’ Amplitude (6)

In the music library at the Barbican Centre in London, the walls are lined with symphonies and sonatas, rigoletti and reference books for jazz and opera. Two men gossip about a composer. A man wearing headphones is silently learning the piano. His teacher, a woman with a grey bob, sits next to him at the electric keyboard and nods. The atmosphere is hushed and people work at shared tables, or listen to music in booths. It’s here that I open Paul Munden’s collection, Amplitude (2022), and realise that it is a kind of musical encyclopedia, moving from classical to baroque to the Romantics, from jazz to film scores to synth-layered noise to the Beatles. Told over 145 pages of poems, it is a playlist, a score, a symphony in six movements, its music telling “the essential story” of the poet’s life (87). It opens with an epigraph, a line from Nietzsche: “My soul, a stringed instrument, sang to itself, invisibly touched” (4).

The collection starts with a stop. In the opening poem, ‘Baroque,’ something snaps while the poet tunes a violin – not a string, but a tendon (5). It is a rupture that launches the collection, the repair of which one hopes to witness as the poems unfold. We can see in poems such as ‘A Gift,’ where the poet retreats to a quiet room at a raucous party (also to tune a violin), that the instrument is not a simple pastime. It is a proxy for the poet’s voice, a way of speaking and a means of participation. In an orchestra, one’s own part joins others to build the picture of a whole; to create a symphony, rich with layering. This is what the poet craves: “sensory fill,” a “stereo-phonic” surround-sound experience (7; 7). Instead, unable to play, he drifts towards “monotony” (meaning ‘single note’) and isolation (7). There is a sense of a rupture greater than that of a tendon, of loss so significant that life’s symphony has retreated towards the lonely note-by-note music of a broken chord. Over the course of the collection, the reader pieces the fragments together, a sense of understanding emerges, and we follow the poet’s slow return to being part again of the orchestra of life.

Most of the poems are derived from sonnets. In what Munden calls “half-rhyming triple-deckers of 42 lines,” stanzas are split in half and zigzag across the page, the way a hand moves through an arpeggio (a broken chord) (145). Or perhaps the flow of stanzas from left to right to left is the shape of a wave, not only water but sound. In layman’s terms, ‘amplitude’ means ‘volume’ – louder, quieter – but, technically speaking, it is displacement of a sound wave from the equilibrium position. Reading, one is always rocked, knocked off balance, recovering. Rhymes are re-located. They are, symbolically, gone too soon or late. It is hard to see where a poem might be going: the poetic form of love and longing is broken up into a series of hairpin turns and the neat resolution we expect is disrupted. In ‘‘Road Closed’,’ the poet ignores a sign and drives along a “sequence / of hairpin bends / towards the summit” only to find a “sudden, huge stone / fallen in the road” (58; 58). A warning then for ignoring signs, as if the reader is being implored: pay attention. Be alert to signals that might help make sense of a pervasive sense of dread.

Apart from the sonnet variations there are also prose poems, which skip by association between different chapters of memory. Words and motifs repeat and retreat, subtly shifting in meaning with each return. In ‘Orange,’ the colour threads through a lifetime, first as a slug of paint, then a coil of fruit peel, then a neon cord tied around a copy of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (54-55). In the section ‘Sightreading La Sirenetta,’ a young child bounds across a landing to ask her father about a city where the streets are made of water. In the following poem, dedicated to the poet’s daughter, two people navigate the streets of Venice. In the next, a girl is dangerously close to a pond. In ‘Enfant Terrible,’ a father is “drinking himself to death under a harsh southern sun on the far side of the world” (10). Later, in a section entitled ‘Intermezzo: Australia,’ the poet sits at his “father’s / desk—I want to see / what the past looks like once it’s travelled / across the world” and sees, in a “quarter bottle of cognac,” “deep within the ripples of Christmases past, is the future” (46; 45; 45). In ‘Sound Effects,’ the sound of a wedding party in full swing skips from the “noise of purest joy,” through the molten creation of a bronze bell to the music of a church ritual that may be matrimonial or funereal (76-79). A cassette with a date written on it launches the memory of a wedding yet is full of foreboding; a happy moment when life is all ahead is counterpoint to a moment when it is suddenly, terribly, over:

I stumble on the penciled date

31st October, 1981, and as I slip the forgotten tape into the deck

and press play, I hear not only a famous toccata, but a pivotal six

minutes of my life; the breathy detail of that autumnal afternoon;

a ritual concluded; everyone making their way from the church

to where the music stops.

(79)

This echoing or, as Munden calls it, “pre-echoing,” builds to create a sense that something will happen, a looming sense of “impending shock” (8; 140).

This feeling, of not knowing where you are going while simultaneously knowing how it will go, is the feeling of sightreading music. Although one encounters a score through parsing symbols in real time, a musician will know that before one even starts, one is primed with instructions for how to play. A sightreader will first scan the Italian notations peppered throughout the score for clues: how to interpret the music; how to understand its mood and how it changes; how to understand the music’s narrative arc. Cantabile, con brio, vivace, doloroso, adagio: in a singing style, with spirit, lively, mournfully, at ease. There are clues in the poems for how to read Amplitude too: Venice, water, the colour orange, the violin, the abyss of drink, Australia. Follow them and find a way through, Munden seems to suggest. The noise of signs and symbols will translate into music; meaning will reveal itself. In ‘A Prima Vista’ (literally, ‘at first sight,’ meaning sightreading), he says “we knew / from our one, / careful, dual scan / of the city’s notation / to make it through” (27).

When musical earworms get stuck in your head, playing and re-playing a fragment of a tune, it is because your brain is trying to complete a broken phrase. The cure is to play the song on repeat until you know the whole phrase and how it fits together; until the siloed musical memory is integrated back into the whole of the song. I have read that dreams may work in a similar way, shuffling through a flip-book of memory and imagination, testing which scenes cause a spiked heartrate or a sense of calm, so that it can be filed away accordingly. Perhaps when life’s narrative is interrupted by a deep trauma, the brain takes the same approach, returning over and over to the memory of the event, trying to integrate it back into the whole of our lives. In ‘[untitled],’ the reader is brought into the poet’s sorting mind, where he tries to place his most wretched memories into an “eerie gallery / of what doesn’t exist” (137). Throughout the collection, we return with the author to old rooms, old songs, old cassettes and records, old films, old roads, old photographs, the meaning shifting slightly with each return, so that it is first sweet, then sad. In ‘Glass Harp,’ glasses are raised – “mine half empty, yours half full, Gb, F#” – the same, identical note is viewed first one way, then another. One flat, one sharp; one a step back on the keyboard, another a step forward.

The price of joy is that it can become the source of your greatest pain. Anyone who has experienced heartbreak will know the agony of a mind dragged unwillingly to return to once-kind memories. How the memory of love can be “a relentless, mournful, broken chord,” a “haunting [is] still present when you wake” (78; 78). But Amplitude seems to suggest that memory can offer a path from the broken chord of loneliness back to the full chord of life. What is a “stereo-phonic sense of time” if not the full-body immersion of memory? Memory is both recall and re-living, action of the past flooding the present. Our lives are thick with layering: themes reoccur over and over; memories play out in harmony and in discord with our present lives; the people we live with and love and lose return to us as a “looming palimpsest / of you, and you” (‘[untitled],’ 136). It is apt that Amplitude returns often to Venice, with Invisible Cities as its playbook. In Calvino’s masterpiece, fragmented ghostly scenes play out over one other, building a picture of a city that is both mirage and intensely real, capturing the feeling of Venice the way we recognise people in our dreams. Only when we look at it all – not one layer, but the lush, layered symphony, thick with reverb, counterpoint and reprise, with phrases returning first major then minor, first one way then another – do we see the many parts that make the whole. That is how one makes sense of a life; how one makes sense of being one human in all the world in all of time. That is how one feels a part of it. “I want that” (7).

the subtly modulated

amplitude

of filtered square

or sawtoothed wave

and give it soul—

science

the engineer

of sentiment, mood…

of a layered narrative,

something akin

to poetry, even love

(‘WYSIWYG,’ 73)

In ‘WYSIWYG,’ the synthesiser seems to offer the poet a way back. The electronic experience is an embodied one: amplified sound, rich with layered frequencies, is one that you feel in your ears, your chest, the muscle in your legs, your breath, your bones. If it is loud enough, you feel that you become an instrument yourself, resonant as a struck bar on a xylophone, humming with sound. To feel again a part of the orchestra of life, one has to become the instrument.

Unplanned Encounters by Jake Goetz

Unplanned Encounters by Jake Goetz

The Exclusion Zone by Shastra Deo

The Exclusion Zone by Shastra Deo

Amplitude by Paul Munden

Amplitude by Paul Munden